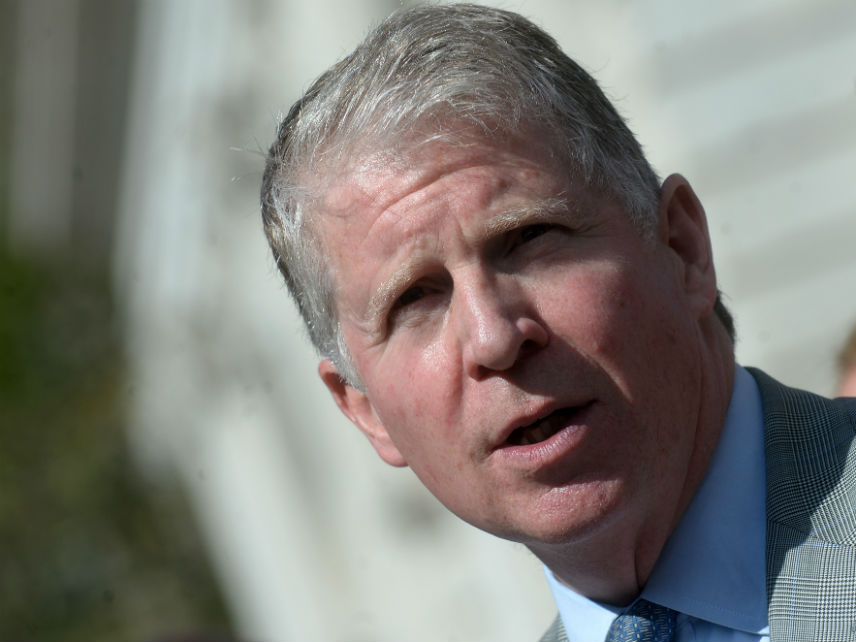

Manhattan D.A. Spent $250K in Asset Forfeiture Funds on Fine Dining and Luxurious Travel

The expenses included five-star Parisian hotels and sumptuous dinners.

Manhattan District Attorney Cy Vance spent nearly $250,000 over the past five years from a state asset forfeiture fund on fine dining, first-class airfare, and luxurious hotels, according to public records obtained by The City, a nonprofit news outlet in New York City.

While regular state employees, like the line prosecutors under Vance, are bound by strict travel and expense rules, Vance is under no such regulations, and his office controls more than $600 million in funds seized by New York law enforcement in civil and criminal cases.

During his frequent trips across the country, Vance lived high on the hog, The City reports:

Expense reports show that in the last fiscal year alone, Vance visited Washington nine times, Aspen and London twice, and Paris and Los Angeles once apiece.

While in Paris, he spent four nights at Hôtel d'Aubusson, paying $2,816. The five-star hotel "is housed in a true Parisian mansion dating back to 1634" and boasts "discrete luxury, Louis XV furniture, original Aubusson tapestries and a wonderful wood burning fireplace," according to a description posted on TripAdvisor.

In London, Vance was booked at the Ned Hotel, paying $994 for a two-night stay. The five-star accommodations are located in a former bank described on the hotel's website as an "abandoned architectural masterpiece," with a rooftop pool that overlooks St. Paul's Cathedral. Vance spent $128 for a meal in the hotel's restaurant, records show.

Notably, The City reports that Vance's spending over that period dwarfs that of district attorneys in New York City's other boroughs. The next highest spender was Bronx District Attorney Darcel Clark, who expensed $18,407 since taking office on Jan. 1, 2016.

Vance defended the spending in statements to The City, saying they were within the rules and involved travel to important policing and counter-terrorism conferences. Vance's office has also spent $38 million in forfeiture funds to help local prosecutors across the country test rape kits.

But the report highlights one of the chief criticisms of asset forfeiture: The loose rules and lax oversight over how those funds are used.

Civil asset forfeiture laws allow police and prosecutors to seize property—cash, cars, and even houses—suspected of being connected to criminal activity. Much of that money is often funneled back into police department and district attorney offices' budgets.

Civil liberties groups argue that creates a perverse profit incentive. Many states have lax reporting requirements for forfeiture expenditures, and numerous watchdog and media investigations have revealed local police departments and prosecutors using forfeiture revenues as a slush fund.

Local news outlets reported earlier this year that the district attorney in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, used $21,000 in asset forfeiture revenues intended for drug enforcement to lease a 2016 Toyota Highlander.

In Macomb County, Michigan, county officials launched an audit of the local prosecutor's office after a successful public records lawsuit revealed more than $100,000 in questionable expenditures from the asset forfeiture fund, including office furniture, birthdays, and retirement parties.

In Illinois, former La Salle County state's attorney Brian Towne is facing criminal charges for misconduct and misappropriating public funds after he allegedly spent asset forfeiture funds on an SUV, WiFi for his home, and local youth sports programs. Town created his own highway interdiction unit and asset forfeiture fund for his office, an unusual move that the Illinois Supreme Court later ruled was illegal.

A 2016 Department of Justice Office of Inspector General audit found that an Illinois police department spent more than $20,000 in equitable sharing funds on accessories for two lightly used motorcycles, including after-market exhaust pipes, decorative chrome, and heated handgrips.

There was also the Georgia sheriff who purchased a $90,000 Dodge Viper with forfeiture funds for the department's DARE program—not to be confused with the other Georgia sheriff who bought a $70,000 Dodge Charger Hellcat with forfeiture funds.