Will California's Proposed Bail Reforms Lead to More People Behind Bars?

Changes in a bill have caused civil rights representatives to take a step back.

Supporters of bail reform are turning against a California bill that they initially helped craft, fearing changes in the legislation could actually lead to increased jailing of those who are awaiting trial.

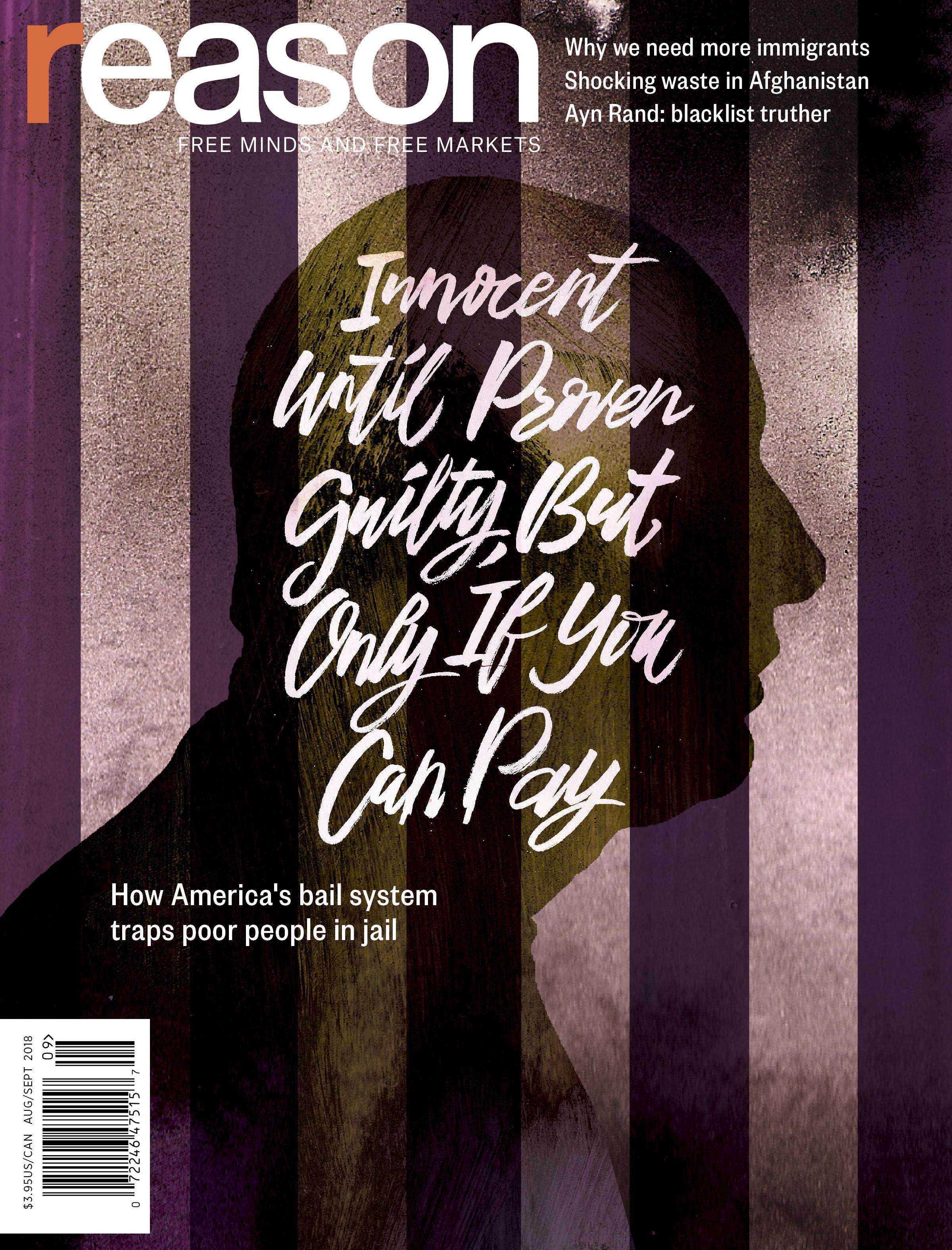

California is looking to follow in the footsteps of states like New Jersey and Alaska and eliminate as much as possible the use of cash bail to decide who is detained in jail awaiting trial. The overdependence on cash bail in our pretrial justice system has led to hundreds of thousands of Americans sitting in jail cells who haven't yet been convicted and are not deemed dangers to the community or flight risks; they simply cannot afford the bail money the courts have demanded.

SB10, introduced in California last year, would replace cash bail schedules with a risk assessment and pretrial system in which courts would determine who is jailed prior to trial on defined dangers to the community or flight risks, not on money. The goal would be to detain only those that the courts worry would either skip out on trial or potentially hurt other people if they were free.

This would be a huge change in the way many courts in California operate, and there are some challenges here. Eliminating cash bail can mean many more poor people don't have to languish in jail (disrupting their lives and livelihoods) waiting for trial. But it also means judges and courts are granted the power to detain people with no way of seeking release at all. This can end up backfiring. In Maryland, where judges were told to reduce their reliance on cash bail, some communities (Baltimore in particular) saw an increase in the number of people who were being detained in jail prior to trial.

Criminal justice reform advocates are therefore very particular in how they want to see the pretrial system reformed. The goal is to get more people out, not leave more people stuck. These advocates were involved in crafting SB10. But the text of the bill since it was first introduced has been changed. And those changes have caused some who helped craft the bill in the first place to either turn against it or at least turn away from it because they fear it will now lead to greater numbers of Californians being held in jail while waiting for trial.

Central to this fear are any potential biases that could be introduced by whatever assessment tool is used to calculate the risk involved in releasing a defendant prior to trial. Civil rights group fear that an overdependence on algorithmic mechanisms to calculate a defendant's risk factor can—when ineptly applied—instead reinforce the same systemic biases that have led to the pretrial incarceration problem in the first place. Some assessment tools that operate on the basis of demographic data—where a person lives, employment status, nonviolent crime history—stick a person in a higher risk category partly because of past biased policing practices. A pack of civil rights and criminal justice reform organizations recently signed onto a letter expressing their fears about reliance on assessment tools and explaining six principles they want used to make sure that these tools didn't continue to perpetuate biases that keep poor minorities trapped in jail even before they've been convicted of a crime.

The American Civil Liberties Union of California, one of the groups involved in crafting SB10, put out a statement yesterday withdrawing support for the bill because the new changes seem to run into this problem. The bill does call for the creation and implementation of assessment tools that would reduce biases in the decision process, and it will require the collection of demographic data about race and gender and other factors to determine whether these pretrial decisions are being made fairly. But it vests all the power over the development and implementation of these assessment tools to the courts themselves. California's Judicial Council, the policy-making body of the state's court system, will be calling the shots.

This is not how many bail reformers want to see change happen. The ACLU wants the development and implementation of these assessment tools to be more independent of the state's judicial system. Natasha Minsker, the center director for the ACLU of California Center for Advocacy and Policy, explained why the ACLU was no longer supporting the bill and is now taking a neutral stance:

Any model must include data collection that allows independent analysis to identify racial bias in the system, supports the use of independent pretrial service agencies recognized as the best practice in pretrial justice, and ensures stronger due process protections for all Californians, no matter where they live.

Jeff Adachi, a public defender in San Francisco, is taking a harder line than the ACLU. He thinks SB10 will actually make problems worse. He believes the bill gives judges far too much power to detain defendants prior to trial. As he writes in the San Francisco Chronicle:

The legislation would also undermine our constitutional right to equality before the law by sorting defendants using crude "risk assessment" tools that are notoriously biased against people of color and the poor. It would then erode due process rights by granting judges overly broad powers to throw these people in jail before trial without input from defense attorneys or the community.

This fracture among reform advocates, combined with the bail industry lobbying hard against the bill, might make it tough to pass.