New Study Shows Drug War Sends Users to Dark Web

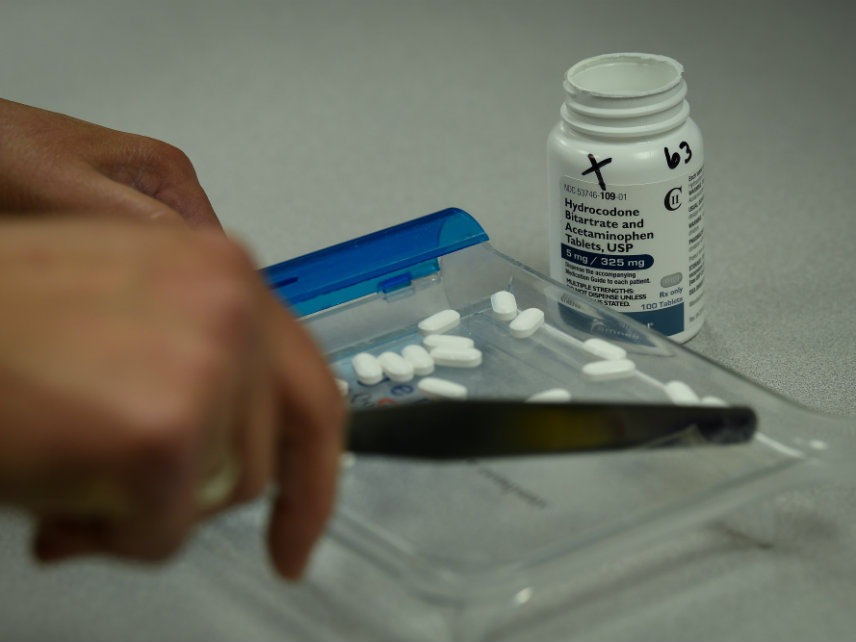

A new British study shows that rescheduling hydrocodone, a powerful opiate painkiller, just forced users onto the darknet to get their fix.

A new study published in the British journal BMJ says restricting the supply of illegal drugs forces users into black markets, where the drugs get more dangerous and more addictive.

The authors of the study looked at the effect of the DEA's rescheduling of hydrocodone in 2014 from a schedule III drug to a more tightly controlled schedule II drug on the sales of illicit prescription opioids on the darknet. They examined the data from 31 of the largest cryptomarkets in the world on prescription opioid sales from October 2013 to July 2016.

In this period, "the percentage of total drug sales represented by prescription opioids in the US doubled from 6.7% to 13.7%," and fentanyl, an analgesic that is far deadlier than heroin, went from being the least purchased drug in July 2014 to becoming the second most purchased drug three years later. The paper also found that there were no significant changes in the sales of non-opioid drugs.

It's no surprise that opioid sales went up on the darknet, given that pain patients and addicts have to get their fix somehow and the internet has made illicit products much more accessible. The fact that exclusively opioid sales went up is indicative of the rescheduling's effect on drug sales.

The results are also demonstrative of the iron law of prohibition—"the harder the enforcement, the harder the drugs," as Richard Cowan, an American drug legalization activist famously put it. Drug dealers, seeking to efficiently transport their product through waves of law enforcement, will have to increase the concentration of their drugs. This leads to opioids like heroin being cut with such chemicals as fentanyl, often without users being aware of the additives. Individuals who cannot obtain their pain medicines legally will end up going to the black market, where the sales are murkier, and the drugs more dangerous. In other words, precisely what is shown in the BMJ study.

What does this mean for policymakers looking to address the opioid crisis? It means that the supply-side approach, in which governments try to restrict access to drugs, is not working. Legislators must seriously reconsider the consequences of the war on opioids. Restricting pain medications will only force addicts into alternative markets where fentanyl is common, leading to overdoses, while leaving law-abiding pain patients with their chronic pain. The data also indicates that cutting opioid prescriptions does nothing to reduce opioid deaths, and in fact is associated with a rise in opioid-related deaths.

If anything, this study is indicative that the war on drugs must be rolled back. Relaxing regulations on the manufacture and sale of opioids will pull people out of the dark recesses of the internet and reduce the distribution of the more dangerous opioids on the market.