New York Times Goes Off the Rails With Claims About Secret Koch Plot to Kill Public Transit

A failed ballot initiative in Nashville had much more to do with hum-drum local factors than shadowy billionaire-backed conspiracies.

A light rail ballot initiative in Nashville, Tennessee, went down in flames last month when two-thirds of voters rejected a $9 billion transit plan that would have hiked taxes on sales, hotels, car rentals, and businesses to pay for 20-plus miles of light rail and new bus rapid transit lines.

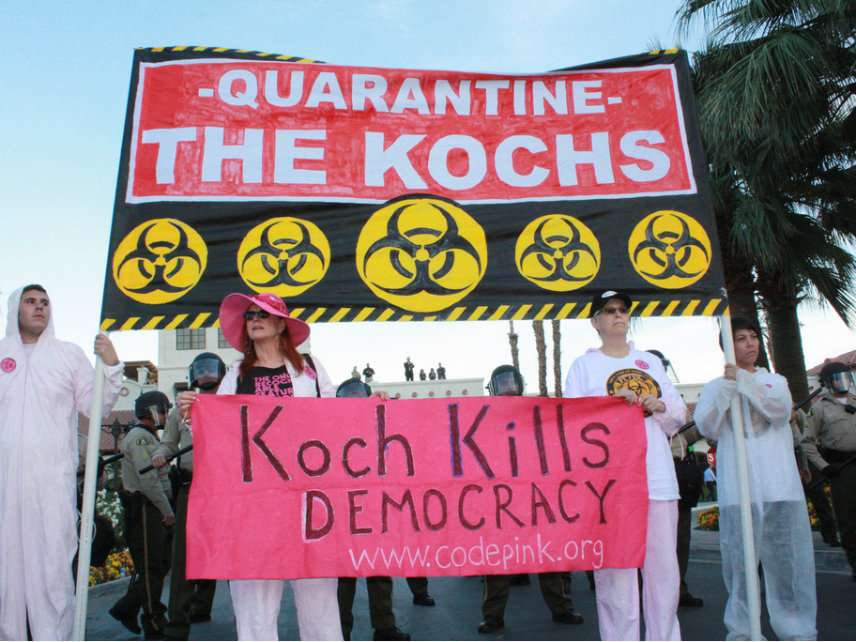

Apparently, it's all the Kochs' fault.

That's according to The New York Times, whose subtly-titled Tuesday article, "How the Koch Brothers Are Killing Public Transit Projects Around the Country," lays the blame for the defeat of this ballot measure—and a handful of other failed local transit initiatives—squarely at the feet of the billionaire brothers.

According to the Times, the Kochs have been deploying an army of Astroturf activists from Americans for Prosperity (AFP), a Koch-funded group, to successfully stop otherwise necessary and popular transportation measures that run against the pairs' ideological and financial self-interest. (Charles and David Koch also support Reason Foundation, the nonprofit that publishes Reason.)

"The Kochs' opposition to transit spending stems from their longstanding free-market, libertarian philosophy. It also dovetails with their financial interests," writes the Times. "One of the mainstay companies of Koch Industries, the Kochs' conglomerate, is a major producer of gasoline and asphalt, and also makes seatbelts, tires and other automotive parts."

Fearful that demand for these products would fall should Nashville build a light rail network, the theory goes, the Kochs' tapped their Tennessee AFP chapter to wage a get out the vote campaign that saw activists make 42,000 phone calls and knock on some 6,000 doors. This activism flipped what was supposed to be a slam dunk into a crushing defeat.

It's a deliciously plausible narrative for those who see nefarious machinations behind anything remotely connected to the Kochs. It's also a story that falls apart upon a closer examination of the details.

For starters, it's hard to believe that the canvassing operation of a single organization—no matter how effective—would be able to produce a landslide victory for a "no" campaign that was going up against some pretty stacked odds. (As the Times noted, the light rail expansion "was backed by the city's popular mayor and a coalition of businesses. Its supporters had outspent the opposition, and Nashville was choking on cars.")

Indeed, when the Tennessean's Nashville reporter Joey Garrison analyzed the reasons for the campaign's defeat, the Kochs and AFP didn't even make the list. Instead, he pinned the blame on things like the decision to put the light rail initiative on the low-turnout May ballot; opposition from black leaders and voters concerned about light rail–spurred gentrification; a muddled promise-all-things message from the "yes" campaign; and the untimely mid-campaign resignation of Nashville mayor and light rail superfan Megan Barry, who was forced out of office over a sordid sex-and-spending scandal.

Former Nashville City Councilwoman Emily Evans likewise failed to mention the Kochs in her rundown of what went wrong for Nashville transit enthusiasts.

"There were a host of reasons [the proposal failed], like the cost ($9 billion), the scale (20 plus miles of light rail), the funding source (sales tax increase) and the financing structure (a decade of interest-only payments)," said Evans in an email to CityLab.

These are more plausible explanations, but they lack the dramatic appeal of shadowy monied interests subverting democracy from afar.

This is not to say that AFP had no effect. The Times article describes an effective outreach campaign that focused on contacting suburban voters likely to bristle at the idea of a massive tax increase to pay for a light rail system few of them would use. (Nashville's light rail plan would have boosted sales taxes to the highest rate in the nation.)

This is hardly as conniving as the Times story makes it out to be. Instead, AFP's actions show the benefit of money in politics as a way to boost voter engagement in what would have otherwise been a low-turnout, low-information election.

Contrast that with Seattle's $54 billion Sound Transit 3 light rail initiative that easily coasted to victory over a practically non-existent opposition and is now facing a fierce public backlash from voters who missed the fine print about all the taxes and fees included in the initiative. Had a more effective opposition campaign been mounted, the electorate might have been more cognizant of these costs when they voted.

More ludicrous still is the idea that the Kochs are taking special interest in light rail initiatives in an attempt to shore up demand for gas and auto parts. Despite increasing transit spending by all levels of government, car sales continue to trend comfortably upwards as do vehicle miles travelled. Fuel consumption is down from a pre-recession high, but that has a lot more to do with increasing fuel efficiency than a sudden popularity of mass transit. (With the exception of growing and densifying Seattle, transit ridership is down in real terms across the country.)

Indeed, were the Times looking to find a clear profit motive in Nashville's light rail fight, it should have taken a closer look at the "yes" side.

One of the main contributors to that campaign was the Citizens for Greater Mobility PAC, which spent roughly $2.1 million on the initiative, nearly double the money spent by the "no" side.

According to campaign finance disclosure reports, donors to Greater Mobility included a number of engineering firms who offer transportation expertise, including CDM Smith (who gave $55,000) and CH2M Hill ($15,000), HDR Inc ($25,000), and Smith Seckman Reid, Inc. ($25,000). The National Association of Realtors kicked $150,000 to the PAC. (Real estate prices tend to go up when a light rail line goes in.)

Even industries the Times intimates have a financial interest in fighting light rail chipped in to the pro side, including tire company Bridgestone, which gave $100,000 to the Greater Mobility PAC. Apparently the benefit of having a major transit station installed a couple blocks from its national headquarters and right in front of a hockey arena that bears its name—as the Nashville light rail plan called for—outweighed the lost revenue from new train takers no longer needing tires.

Which is not to say that there is anything necessarily unseemly about these donations either. Transportation ballot initiatives represent interest group politics in their rawest form, pitting suburban drivers (and sometimes urban bus riders) against city rail riders, downtown property owners, and anyone who stands a chance of landing a construction contract on the coming project.

Rather than portraying Nashville's transit fight for what it really was, however, The New York Times chose instead to craft an unsupported and unconvincing narrative about shadowy billionaires pursuing a vague financial interest.