Trump's Economic Illiteracy Has Deep Roots

In Trump's mind, America loses when it buys too much. And it loses when we sell too.

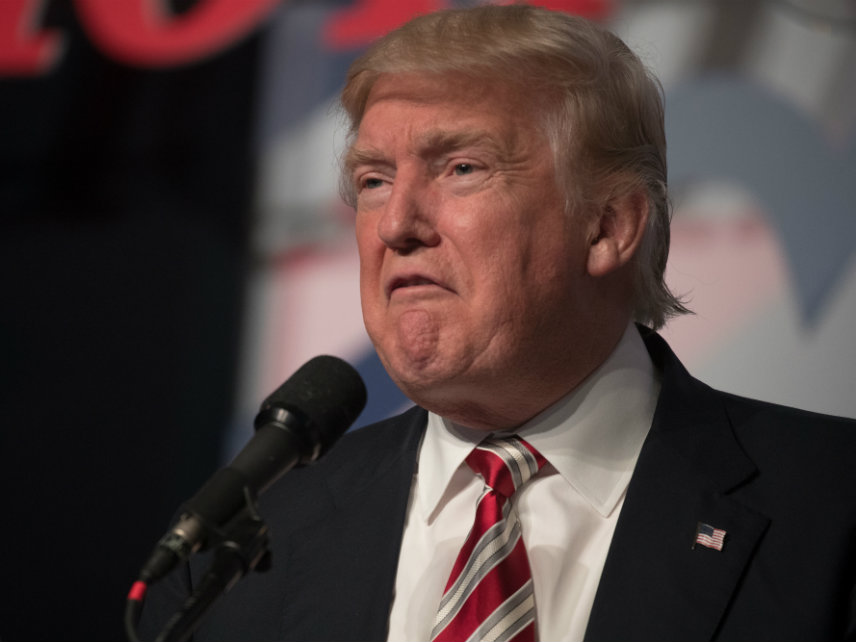

When Russ Roberts, the George Mason University economist and host of the EconTalk podcast, visited the Reason office last week to be a guest on our podcast, he was asked about President Donald Trump's economic policies. Roberts offered a succinct, and powerful, rejoinder to the president's view that America's trade deficit with China is a problem—an opinion that Trump has repeatedly expressed since well before his campaign for the presidency began, and one that seems to lie at the center of his hardball trade tactics with one of America's largest trading partners.

"It is certainly true that China doesn't play fairly in the economic game of international trade," he said. "But not because we run a trade deficit with them. That's not a result of unfairness. That's the result of the fact that we, in general, import more stuff from the rest of the world than they import from us, and at the same time they invest more in the United States than we invest in their countries."

That's neither uniformly good nor uniformly bad. It means that America is a good place to invest, and that's why people invest their money here. That capital surplus means that Americans generally have more money to spend on goods and services—hence why we run a trade deficit with other countries.

This basic dynamic of macro-economics seems lost on the current occupant of the White House. But Trump's hostility toward China—and, more importantly, the underlying idea that trade is a zero-sum game with winners and losers—is not the product of his late-in-life transformation from hotel mogul to reality TV star to politician. It fits with the rest of the nationalist economic message Trump used to catapult himself to the top of an increasingly nationalistic Republican Party, but it has roots that go deeper than that. For a man as inconsistent as Trump, he's been remarkably consistent on his views of international trade for decades.

Unfortunately, he's been consistently wrong.

Here's something Trump said in a 1990 interview with Playboy:

I think our country needs more ego, because it is being ripped off so badly by our so-called allies; i.e., Japan, West Germany, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, etc. They have literally outegotized this country, because they rule the greatest money machine ever assembled and it's sitting on our backs. Their products are better because they have so much subsidy. We Americans are laughed at around the world for losing $150 billion year after year, for defending wealthy nations for nothing, nations that would be wiped off the face of the earth in about 15 minutes if it weren't for us. Our "allies" are making billions screwing us.

If you didn't know those comments were 28 years old, you might think they were plucked from the president's Twitter feed this morning (minus the mention of "West Germany"). The basics of Trumponomics are right there. We are being "ripped off so badly" and we are being "laughed at" by our supposed friends while we are "losing" billions in trade.

In the same interview, Trump talked about how he would like to put "a tax on every Mercedes-Benz rolling into this country and on all Japanese products." He also said he could someday be president because "the working guy would elect me. He likes me." And, lest you think his tendency to praise authoritarian regimes is new, Trump also praised the Chinese for cracking down on the Tiananmen Square protests, because it showed "toughness." No wonder that Playboy interview has become something of a Rosetta Stone for understanding Trump, with foreign officials studying it for clues about how to woo the president.

Jibran Kahn, who highlighted those old Playboy quotes in a piece he wrote last week for National Review, notes, points out that there is one Trump comment in the interview that perfectly highlights his misunderstanding of trade. In describing his concern about the booming Japanese economy of the late 1980s and early 1990s, Trump said the Japanese "double-screw" Americans.

"First, they take all our money with consumer goods, then they put it back in buying all of Manhattan," he said. "So either way, we lose."

Think about that for just a second. When Americans buy consumer goods from Japan—this is the crux of Trump's current complaints about a trade deficit with China—that means America is losing. And when Japanese businesses buy real estate in America, that means America is losing again. Apparently, we are losing whether we buy or sell.

This is some sort of reverse tautology. An argument that is true solely because it is true in Trump's head. There is no arguing with that.

This is not mere economic illiteracy; it is economic illogic. And it is on this basis that Trump is pursuing policis that he doesn't seem to understand. Trump's tariffs have increased the price of steel and aluminum, which have increased production costs for myriad American businesses and left those same businesses at a competitive disadvantage against foreign competitors. Another wave of tariffs against thousands of Chinese goods is planned, and retaliatory tariffs from China will do further damage to American farms and businesses. It's not the Chinese or Japanese who are trying to "double-screw" America—it's the guy who says we need protection from the benefits of trade.

As Roberts said at Reason last week, there's good evidence that China is indeed cheating on trade with regard to intellectual property and technology. But tariffs, he added, are unlikely to solve that problem, and may in fact create many more.

"The trade deficit with China is not evidence that they are cheating," says Roberts. "That part of the Trump story about the tariffs is misleading, xenophobic, and encourages them to put tariffs on our stuff. It's horrible."