Heroin Users Are Less Likely to Be Dependent But More Likely to Die

A new study highlights the gap between rising heroin use and rising heroin deaths.

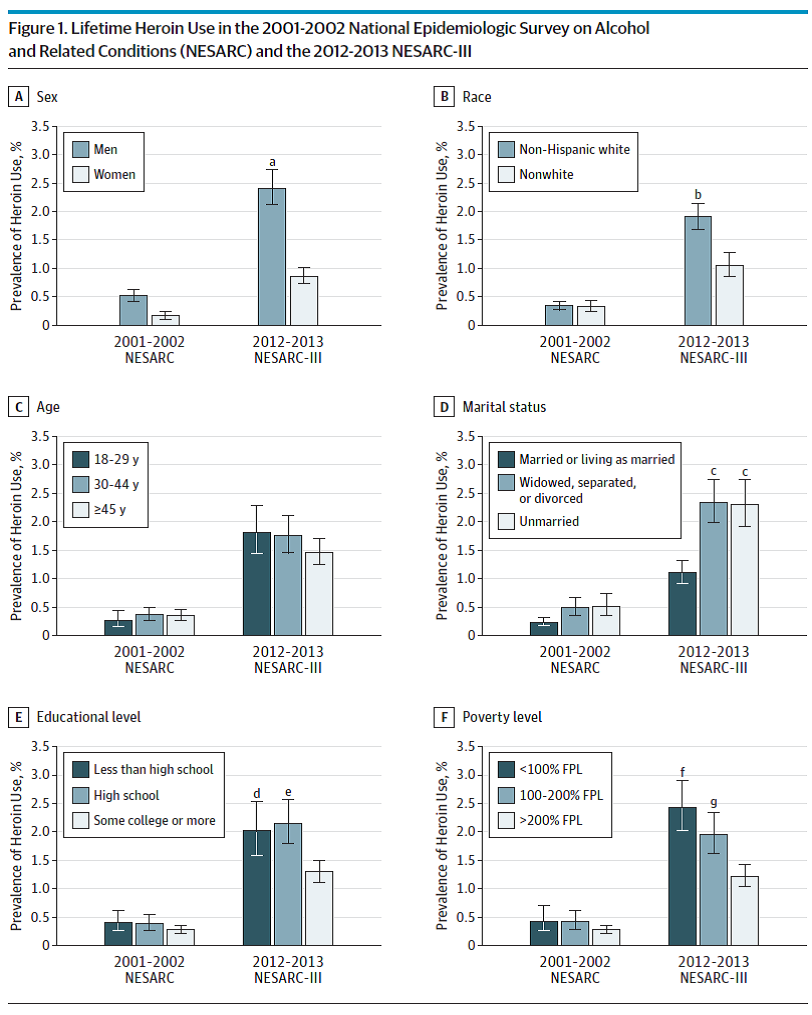

Survey data reported last week in JAMA Psychiatry indicate that the share of Americans who have ever used heroin nearly quintupled between 2001-02 and 2012-13, from 0.33 percent to 1.61 percent. During the same period, according to the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), the share of Americans who have ever experienced a heroin-related "substance use disorder" (which includes "abuse" and "dependence") only tripled, from 0.21 percent to 0.69 percent. In other words, the prevalence of substance use disorders among heroin users fell—by about a third, from 63 percent to 43 percent.

That decrease is counterintuitive, since heroin users are three times more likely to die as a result of their habits today than they were in 2002. Evidently there is a difference between the factors that contribute to heroin-related fatalities and the criteria for a diagnosis of abuse or dependence. Some of those criteria, such as "physically hazardous use," taking larger amounts than intended, and "use persistence despite physical health problems due to heroin," seem relevant to the risk of death. So does frequency of use, which is not one of the explicit criteria but is logically related to them. Yet the percentage of heroin users who have ever used the drug on a daily basis also declined during the study period, from 36 percent to 30 percent. Other factors must be making heroin use more lethal, possibly including an increase in drug mixing (the primary cause of so-called heroin overdoses), greater variability in potency (perhaps related to increased use of powerful adulterants such as fentanyl), or an influx of novice heroin users who are unaccustomed to the unpredictable purity of black-market drugs.

Consistent with that last explanation, the NESARC numbers provide further evidence that many of the newer heroin users switched from prescription opioids. Although prior nonmedical prescription opioid (NMPO) use was not more common in the 2012-13 survey among all heroin users, it was more common among white heroin users. Columbia University epidemiologist Silvia Martins and the other authors of the JAMA Psychiatry study note that "increases in heroin use and related disorders were particularly prominent among white individuals, leading to a significant race gap in lifetime heroin use by 2012-2013." In the second survey, the prevalence of lifetime heroin use among non-Hispanic whites was 1.9 percent, compared to 1.05 percent among the other respondents. "Heroin use appears to have become more socially acceptable among suburban and rural white individuals," Martins et al. say, "perhaps because its effects seem so similar to those of widely available [prescription opioids]."

Still, the prevalence of lifetime heroin use also rose among blacks and Hispanics, even though fewer of them reported prior NMPO use in the second survey. Martins and her colleagues also note that when subjects are divided according to the extent of their NMPO use, increases in heroin use can be seen in every group, "suggesting that factors other than increasingly frequent NMPO use contributed to the increase in heroin use."

The NESARC data confirm that heroin use, despite the dramatic increase in heroin-related deaths (which sextupled between 2002 and 2015, according to the CDC), remains rare in the general population. According to the second survey, 1.61 percent of Americans had ever used heroin, and 14 percent of that group—i.e., 0.23 percent of the general population—had used heroin in the previous year. The rarity of heroin use is the main reason Martins et al. decided to focus on lifetime use rather than past-year or past-month use. "We focused on associations with lifetime use, lifetime disorder, and patterns of lifetime disorder across time, which are important population parameters, particularly for very rare conditions such as heroin outcomes in the general population," they explain. "For very rare conditions (eg, any heroin outcome in the general population), examining lifetime cases may be the only way to determine demographic and clinical correlates and patterns of use during the life course, which simply cannot be estimated from small numbers of survey participants with current heroin use or use disorders."

One point that is apparent in those patterns of use will come as a surprise to anyone who believes heroin addiction is irresistible and inescapable: The vast majority of the heroin users identified by NESARC—91 percent in the 2001-02 survey and 86 percent in the 2012-13 survey—had not used the drug in the previous year. That is similar to the breakdown in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, which in 2015 found that 84 percent of lifetime heroin users had not used the drug in the previous year, while 95 percent had not used it in the previous month.

The fact that someone is not a current heroin user, of course, does not mean the drug never caused him problems. Recall that the second NESARC survey found 43 percent of lifetime heroin users qualified for the "abuse" or "dependence" label at some point. But at the time of the survey, only 7 percent did.

Martins et al. note that NESARC "excluded homeless and incarcerated individuals," and "including these populations would likely increase the overall prevalence of heroin use and use disorder." The same problem afflicts other surveys as well. But surveys such as NESARC and NSDUH still should be useful in estimating trends, assuming that the percentage of users they miss remains about the same over time. Both surveys indicate that past-year heroin use has increased since 2002, but not nearly as dramatically as heroin-related deaths. In fact, NSDUH measured a drop in heroin use between 2014 and 2015, even as heroin-related deaths continued to rise. That divergence is where efforts to reduce the harm associated with heroin use should be focused.