The Fight for Criminal Justice Reform is Moving to the States

New initiatives by criminal justice groups will target state-level reform, where 86 percent of U.S. prisoners are held.

With the once-bright prospects for overhauling the federal justice system now looking grim under a Trump presidency, civil rights and criminal justice groups are turning their attention to the states with ambitious and well-funded plans to reduce the prison population, city by city and county by county.

The American Civil Liberties Union, the MacArthur Foundation, and the U.S. Justice Action Network, a bipartisan coalition of advocacy groups, have all announced plans in recent weeks to redouble their work on criminal justice reform at the local level, where it arguably matters most.

Mass incarceration is "a local problem with local solutions that's national in scope," says Laurie Garduque, the justice director of the MacArthur Foundation. Last week, the MacArthur's Safety and Justice Challenge announced a new round of "innovation fund" grants to 20 different cities. The grants will fund projects ranging from a new risk assessment tools in Campbell County, Tennessee, designed to steer low-income single mothers away from the criminal justice system, to technology to track and analyze racial disparities in San Francisco jails.

Meanwhile, the American Civil Liberties Union is beefing up its Campaign for Smart Justice with the goal of reducing incarceration by 50 percent by 2020. In the coming months, the ACLU will roll out a roadmap for reducing incarceration by half in each of the 50 states.

"States were ground zero for the battle against mass incarceration before the election and ground zero after the election of Donald Trump," Udi Ofer, the director of the ACLU campaign, told reporters in press briefing last month. "This a battle that must be waged and won at the state level."

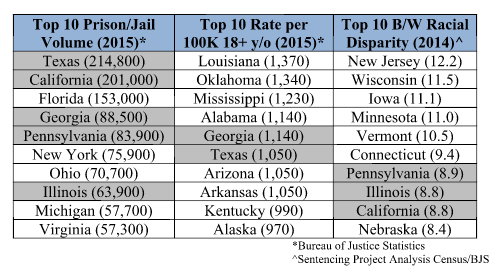

The first round of upcoming ACLU investments will target states identified by the organization as having the highest volume of prisoners, the highest incarceration rates, and the largest racial disparities within their justice systems. Unsuprisingly, the states with the highest volume and rates of incarceration are Texas and Louisiana, respectively, but the states with the worst racial disparities show how large of a task the ACLU is taking on: New Jersey, Wisconsin, Iowa, Minnesota, and Vermont.

The ACLU launched its criminal justice campaign in 2014, supported by a $50 million grant from George Soros' Open Society Foundation and followed by an addition $22 million in donations.

Much of the energy on criminal justice over the past few years focused on reform bills in Congress that would have had a modest but tangible impact on the federal prison population. At the time, it was considered more politically realistic than attempting to tackle the vast and varied state criminal justice systems.

To get an idea of the scope of the criminal justice system outside of the federal government: There are roughly 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the U.S.; 3,142 counties with their own jails, cops, and courts; more than 2,400 elected prosecutors with largely unchecked power; and 50 states with their own prison systems.

As Fordham University law professor John Pfaff has persuasively argued, tackling mass incarceration will involve rethinking not just the war on drugs, but how we as a country prosecute and punish violent criminals. Of the estimated 2.2 million people incarcerated in the U.S., 86 percent of them are in state correctional systems. Non-violent drug offenders only make up 16 percent of the total state prison population. there's no way the U.S. can even get close to cutting its prison population by 50 percent without releasing violent offenders—a much more fraught enterprise for politicians.

Organizations like the MacArthur Foundation believe they can make significant cuts to the number of people admitted to jails, and subsequently prison, by targeting the front-end of the justice system: whether low-level offenders get arrested, whether they're released on bail or put in jail, and what choices the prosecutors and judges make.

"Seventy-five percent of people in jail who are pre-trial or convicted are there for nonviolent offenses," Garduque says. "Many are there for not paying fines and fees, so this has really has been about the criminalization of poverty and over-punishment, and all of that sets you on course for increased involvement with the criminal justice system.

And the MacArthur Foundation believes there is an appetite for this type of front-end reform. Garduque says the foundation received nearly 200 applications from cities in 45 different states for its challenge.

One trend that's also heartening for criminal justice groups: Voters in the 2016 election generally favored criminal justice reform measures and booted punitive prosecutors out of office, even in districts that broke hard for Donald Trump.

For example, last week GOP Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin signed an executive order removing questions about prior convictions from state job applications. According to a poll of Kentucky voters released by the U.S. Justice Action Network on Monday, 82 percent of respondents believed the state justice system is in need of reform, and 91 agreed that there should be fewer barriers for ex-offenders seeking jobs.

"Building on the momentum of the Governor's Executive Order offering second chances for people with records, this poll shows a mandate for changes to Kentucky's broken justice system," Holly Harris, Executive Director, U.S. Justice Action Network, said in a statement. "We look forward to working with legislators from Pikeville to Paducah, and from Florence to Fountain Run on sweeping improvements that improve public safety and take people from jails to jobs."

And in Oklahoma, a state task force on criminal justice reform recently released recommendations to reduce the state's prison population by more than 9,000 beds.

"It's no secret our prison population is in a crisis with over 61,000 people under the jurisdiction of corrections," Oklahoma Gov. Mary Fallin said in her state of the state address on Monday. "Our prisons are way over capacity, and our prison population is expected to grow by 25 percent in the next 10 years."

Of course, not everyone is on the same page. The Alabama governor declared last night in his state of the state speech that "if Alabamians can put a man on the moon, we can build more prisons." Quite the stirring ode to the human spirit.

But between the daily mini-disasters and tweet controversies of the Trump administration, look to the states for real movement on criminal justice issues. That's where the country will ultimately begin the long process of decarceration, or keep building more cages.