Watch the Lamest Arguments Against Criminal Justice Reform

Courtesy of the National Association of Assistant U.S. Attorneys

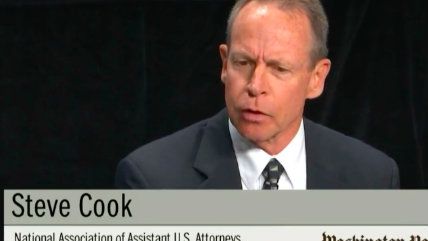

At a Washington Post summit on criminal justice Tuesday, one could hear many thoughtful, earnest critiques of how the U.S. administers justice, and how it could be better. Or you could listen to Steve Cook, the head of the National Association of Assistant U.S. Attorneys.

"The federal criminal justice system simply is not broken," Cook, a federal prosecutor for the Eastern District of Tennessee, told the audience during a panel on sentencing reform. "In fact, it's working exactly as designed."

The NAAUSA has been one of the most vocal groups of prosecutors opposing efforts to roll back federal mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines. It's also a close ally to similarly minded conservative lawmakers in Congress. As I reported on Monday, Texas GOP Rep. Louie Gohmert's office has been circulating talking points and PowerPoint presentations from NAAUSA in an attempt to drum up opposition to a package of criminal justice reform bills expected to reach the House floor this month.

Many critics of the criminal justice system might agree with Cook's first statement, but probably not his follow up assessment.

"In the federal system, less than 1 percent of the individuals incarcerated are there for simple possession," Cook said later in the panel. "Since the mid-80s, we've gone after armed career criminals, kingpins, international drug traffickers, and that's who we're putting in federal prison. That's who the bills in Congress will focus on and reduce sentences for and release from prison."

Cook argued that several pending bills in the Senate and House will "gut" the tools that allowed U.S. Attorneys to prosecute the drug war and allow armed career criminals back on the street. "Beginning in 2015, as a result of the some of the reforms we've seen across the country, we've already seen violent crime spiraling up," Cook warned, citing rising violent crime rates in several major cities. "We're already seeing a reverse of the hard work we've done. The federal prison population has dropped by 11 percent. Federal prosecutions have dropped by 27.4 percent. They're having an impact."

Some of the dangerous "kingpins" who are back on the street are people like Sharanda Jones, who was sentenced to life in prison for a single, first-time, nonviolent drug offense. Because Jones acted as a go-between in a cocaine deal, prosecutors charged her with drug conspiracy, alleged she was the leader of a drug ring, and tacked on several sentencing enhancements that left the judge in her case with no other option but to give her life in prison. Prosecutors also rolled up Jones' family in the conspiracy, including her quadriplegic mother, who was sentenced to 17 years in prison. President Obama granted Jones clemency last year.

One of the other panelists, Kevin Ring, the vice president of the nonprofit advocacy group Families Against Mandatory Minimums, described his own experience in federal prison.

"When I went to prison, I saw people that were serving sentences that were completely disproportionate to their crimes," Ring countered. "It's getting tiresome at this point to hear people tell me who's in federal prison because I was there […] I served with a lot of drug dealers, people who Steve's group might characterize as real 'masterminds' because they got caught in a larger conspiracy. They deserved punishment, and they deserved to be held accountable, but they didn't deserve to be there for 10 or 15 years. That wasn't going to make us safer. It was so clear that these guys were rotting and not getting better."

Republican Rep. Bob Goodlatte, another of the panelists at Tuesday's summit and the chair of the House Judiciary that has crafted and advanced 11 of those criminal justice bills this year, also disagreed with Cook's assessment of his legislation, noting that while the Senate bill does not distinguish between violent and nonviolent criminals, the House version does.

"The House bill has been very careful to look at this and make sure we do not allow any sentence reduction for anybody who's in prison for committing a violent crime," Goodlatte responded. "In fact, we enhance sentencing, and for the first time we would allow somebody who was engaged in armed robbery or carjacking and other things to get an enhanced sentence, a higher sentence, if they are arrested for a subsequent drug offense, because I agree that some drug criminal can be violent criminals as well."

(Goodlatte, like Cook, is no fan of President Obama's expansive commutations. His office released a letter Tuesday expressing "deep concern" about Obama's granting of clemency to many individuals who were convicted of possession of a firearm in the furtherance of a drug trafficking offense—one of the enhancements that prosecutors added to Jones' sentence, as well as that of Weldon Angelos.)

As I also reported Monday, House Speaker Paul Ryan recently met with criminal justice reform advocates, and he has pledged to get the package of bills to the House floor. Goodlatte said he is "very optimistic," that the bills will pass. "Every sentence in everyone one of the bills has been negotiated," he said.

You can watch a video of the panel here.