Foreign Aid Is a Failure

Throwing good money at bad governments makes poor countries worse off.

It's been almost a decade since one of the deadliest natural disasters in modern history devastated the coast of South Asia. In the final days of 2004, a 9.1-magnitude undersea earthquake triggered a tsunami in the Indian Ocean, killing over 230,000 people in places such as Indonesia and Sri Lanka and leaving thousands stranded without the basic necessities of life.

International leaders immediately called on the global community to provide help. What happened after that underscores the flaws in the developed world's approach toward foreign aid: Governments gave generously, pledging more than $10 billion. Yet the humanitarian response to the crisis fell far short, and many desperate needs went unmet.

For years, it was believed that solutions to complex global problems could be engineered if only wealthy nations mustered enough will and funding to see them through. But despite a desire to help and a willingness to give, the international community keeps stumbling to address both short-term crises, such as natural disasters, and longer-term challenges, such as global poverty and economic development.

In his 2013 book Doing Bad by Doing Good, the George Mason University economist Christopher Coyne explains why measures intended to alleviate suffering often go so wrong. Most people agree that wealthy countries have some responsibility to help relieve hardship in distressed areas. But while we are usually clear about our goals, we rarely stop to consider whether government can realistically accomplish them. Our efforts abroad tend to be marred by culturally illiteracy. Without meaning to, we frequently create perverse incentives that harm the people we are trying to assist.

Foreign aid is the main tool of state-led humanitarian efforts among wealthy members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). While such spending accounts for a mere drop in the bucket of the donating nations' budgets, the combined sum from governments around the world is enough to cause big problems in developing economies. In Fiscal Year 2013, OECD countries spent a total of $138 billion on foreign aid. From 1962 to 2012, they contributed a cumulative $3.98 trillion.

It was long believed that directing money to stagnant communities could jump-start economic growth. Yet numerous studies have found little evidence that foreign aid actually leads to greater economic development.

Take Africa as an example. To date, the continent has received well over $600 billion in outside assistance. World Bank data show that a majority of African countries' government spending comes directly from foreign aid. Yet much of Africa remains impoverished, and rampant corruption continues.

Dambisa Moyo has a personal perspective on the matter. In her 2009 book Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way to Help Africa, the Zambian-born economist characterizes foreign aid to Africa as an "unmitigated economic, political, and humanitarian disaster" that has actually made the continent poorer. Africans will never see their governments as legitimate, she explains, as long as most of the spending for education and health care comes from foreign countries.

To Moyo, continued aid spending reinforces the perception that African governments are ineffective and makes it nearly impossible for them to break free from dependence on foreign help. Sketching the sad outcome for outside observers, she writes: "Stuck in an aid world of no incentives, there is no reason for governments to seek other, better, more transparent ways of raising development finance."

Of course, no amount of evidence can dissuade a true believer. Among the foreign-aid faithful is the Columbia University economist Jeffrey Sachs, author of 2006's The End of Poverty and champion of the United Nations' experimental (and controversial) Millennium Villages Project. Sachs acknowledges that foreign aid often fails, yet he still calls for the design of "highly effective aid programs." He is short on details about the specific changes that would distinguish those ideal programs from existing, mistake-riddled boondoggles.

Sachs takes it on faith that aid programs can be made effective. Unfortunately, he and his acolytes have failed to grapple with the fundamental reason so much aid fails: Governments simply do not have enough information to know what each dollar's best use would be. People are forced to compete for resources in the political arena, and money ultimately goes to those with the most connections, not to those most in need.

Aid providers also have trouble figuring out which investments are most appropriate for a particular developing economy, so money ends up being poured into bad projects. These white elephants not only fail to encourage economic growth but frequently divert scarce resources to destructive ends. Aid money becomes a tool of oppression rather than empowerment. As Moyo put it in a 2009 Wall Street Journal essay, "A constant stream of 'free' money is a perfect way to keep an inefficient or simply bad government in power."

New York University's Bill Easterly does an excellent job describing international organizations' tendency to double down on their failures in his 2008 book The White Man's Burden. Like governments, multilateral aid institutions can suffer from central-planning paralysis, which makes it difficult to isolate mistakes and find ways to better serve their "clients."

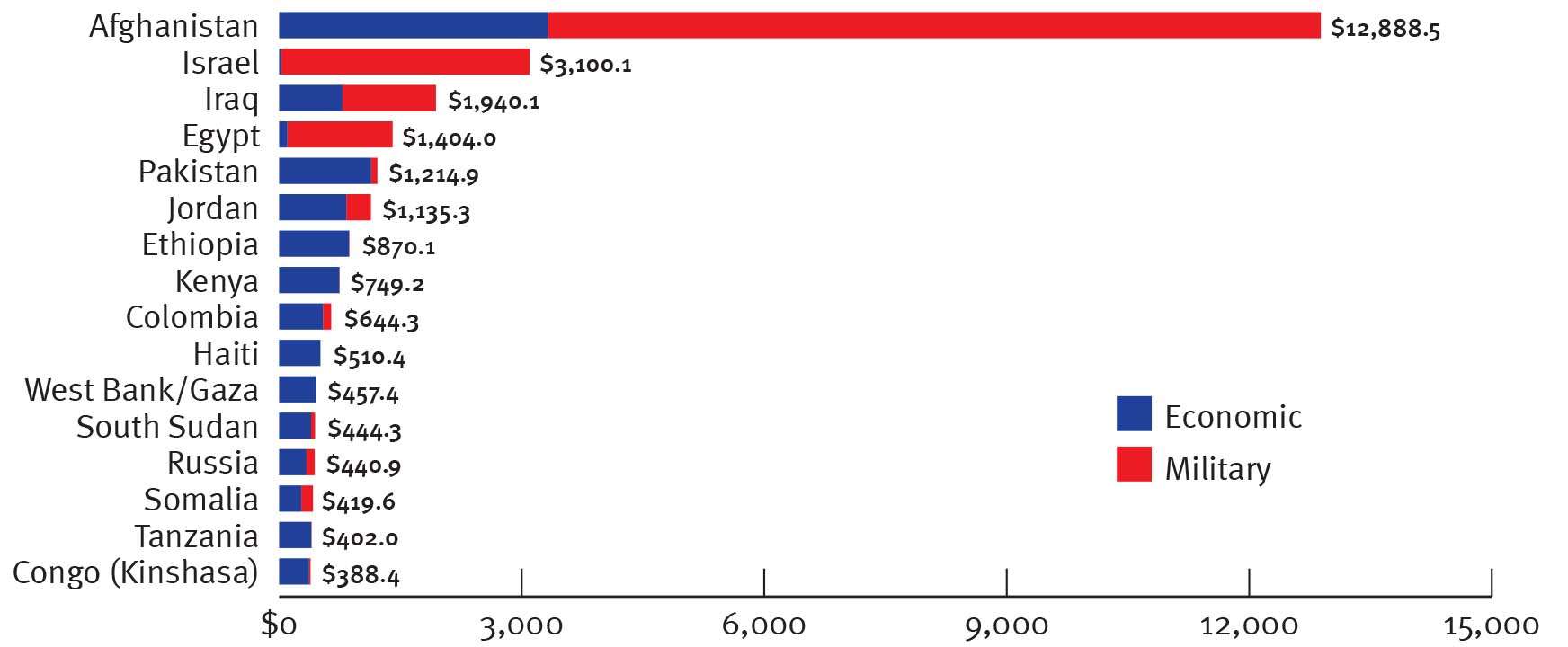

Foreign aid suffers from a principal-agent problem, in which organizations prioritize donors' political and commercial interests over recipients' needs. In 2012, for example, Egypt received $1.3 billion in U.S. military aid. Most of those funds flowed through Foreign Military Financing (FMF), a program that provides foreign governments with grants for the acquisition of U.S. defense equipment and services. One of the program's objectives, according to the State Department, is to "support the U.S. industrial base by promoting the export of U.S. defense-related goods and services." Translated from bureaucratese, that means FMF funnels dollars to foreign governments for the explicit purpose not of helping people on the ground but of benefitting U.S. contractors and manufacturers. The same is true of many other aid programs.

The problems caused by poverty and natural disasters are enormous, but aid's track record suggests that it too often only makes matters worse. Our global neighbors deserve more from us. To serve them well, we must have the humility to admit we don't have all the answers.