The November Man and Life of Crime

Pierce Brosnan gets back in the spy game, Jennifer Aniston takes on Elmore Leonard.

One of the subsidiary pleasures of an old-school spy movie is vicarious globe-trotting. We don't want to watch James Bond or Jason Bourne moping around in some grim Le Carré-style safe house; we want to see them prowling the souks of Istanbul and leaping across the rooftops of teeming Tangier. We want Paris, London, Berlin. Unfortunately, The November Man, a new film shot in the unglamorous but budget-friendly outlands of Serbia and Montenegro, offers virtually none of this traditional spy-flick travel porn. Which would be okay; it's not crucial. However, the movie is also deficient in more important ways that might otherwise compensate for the lack of cool stuff to look at.

The picture marks Pierce Brosnan's return to the spy genre a dozen years after he bowed out of the Bond franchise. He's 61 years old now, but still dapper, and he gamely plays his age. His Peter Devereaux is an old CIA hand retired to Switzerland after a botched mission five years earlier in which his protégé, a young agent named Mason (Luke Bracey), unintentionally killed a small child. Since then, Devereaux has been sorting through his many regrets and quietly cultivating his drinking problem. But now his former controller, Hanley (Bill Smitrovich), wants to lure him back into the game. An operative named Natalia (Mediha Musliovic)—Devereaux's former love interest—has the goods on a high-level Russian politician named Federov (Lazar Ristovski), a very bad guy who looks likely to become his country's next president. Only Natalia's damning intel can prevent that, but she needs help getting it out of Moscow. She needs Devereaux.

The movie is based on a 1987 espionage novel by Bill Granger, a book that Brosnan struggled for years to bring to the screen. The story has been adjusted out of the Cold War period, creating attendant confusions. (Prospective viewers might want to brush up on the history of Russia's violent interventions in Chechnya.) The narrative also gets fairly crowded, and after a while it begins to lumber. Devereaux is compelled to team up with a Belgrade refugee worker named Alice (onetime Bond girl Olga Kurylenko). Soon they're being pursued by Federov's sleek female assassin (Amila Terzimehic) and, separately, by a CIA hit team led by Devereaux's old partner, Mason. Devereaux suspects something's not right here.

This being a very generic genre movie, all the usual computer-y spy tech is brought to bear in magically tracking the fugitives' every move. (People say things like, "I want eyes on him right now!") There's a time-out interlude in which Alice sits down at a piano and begins to play, and Devereaux cocks an ear and says, "Satie?" There's also a jolly pimp, a cluster of topless strippers huffing cocaine off a nightclub table, and an expatriate American girl (Eliza Taylor) who's brought in for no other reason than to provide a sex scene and then have a major artery slashed open with a knife.

Veteran director Roger Donaldson, who also teamed with Brosnan on the 1997 disaster hit Dante's Peak, provides some bracing jolts of violence (a shovel to the face, a bullet blowing out the back of a man's head); but most of the action—the usual chasing and punching and shooting—is not very stylishly staged. And there's some rape imagery toward the end that's more leeringly nasty than it needed to be.

Brosnan is fine, in a time-biding way, and Kurylenko is more than just beautiful set dressing. But the movie lacks class and dash. It might have been improved a bit by relocation to more exotic terrain (Prague? Pittsburgh?), and even more by leaving the surprise-free story behind.

Life of Crime

Elmore Leonard's terrific crime novels, with their sly plots and masterfully compressed dialogue, all seem ready-made for the movies, and 17 of them have been duly adapted to date. The latest, Life of Crime, based on Leonard's 1978 caper tale The Switch, is a middling entry, nowhere near as dreadful as the 1985 Stick (directed by Burt Reynolds!), but still short of the standard set by Steven Soderbergh's Out of Sight, Barry Sonnenfeld's Get Shorty, and Quentin Tarantino's Jackie Brown. Scripted and directed by Daniel Schechter, the new picture is unusually faithful to its source (Leonard's crackling lines are sprinkled throughout), but that could be part of its problem—it might have benefitted by being imaginatively refreshed, in the manner of the FX cable series Justified, which is also drawn from Leonard's work.

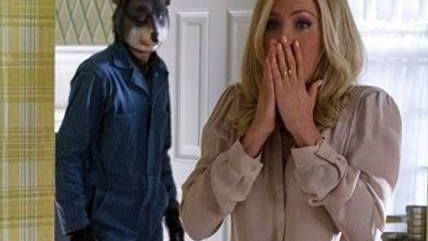

Here we have two ex-cons in 1978 Detroit hatching a foolproof scheme to get rich quick. Ordell Robbie (Yasiin Bey, better known as Mos Def) is the brain behind the scheme; Louis Gara (John Hawkes, of Winter's Bone) is his dim pal, going along for the ride. They've set their sights on Frank Dawson (Tim Robbins), a wealthy blowhard with a sideline in real-estate scamming, the illicit proceeds from which he keeps stashed in the Bahamas, along with a calculating sex bunny named Melanie (Isla Fisher). Their plan is to wait for Frank's next Caribbean sojourn and then kidnap his wife, Mickey (Jennifer Aniston), a woman chafing under her husband's chilly neglect and weary of her gilded country-club existence. Ordell figures Frank will pay $1-million to get her back.

The twist is pure Elmore: after Ordell and Louis snatch Mickey and tuck her away in the house of their co-conspirator, a fat-slob neo-Nazi named Richard (Mark Boone Junior), they learn that Frank has no interest in getting Mickey back—he has already filed for divorce from her, and plans to marry Melanie. This annoying development forces devious realignments among the characters, culminating in a very clever plot turnaround.

The actors are all fine. Aniston, as a woman slowly discovering that her deluxe life has been an empty lie, again demonstrates a knack for breezy deadpan comedy. Bey is solid as a half-smart hipster; Hawkes exudes more warmth than he's usually allowed; and Will Forte has some lively scenes as a suburban sleazeball with carnal designs on the unreceptive Mickey.

But the movie is low on energy—unlike Leonard's book, it never snaps to life. It's not a bad picture, but it's not much more than okay, either. In the graveyard month of August, however, "okay" is often the best that can be expected.