Blame World War I For Whistleblower Persecution—And So Much More

U.S. involvement in World War I lasted just a year and a half. But government today uses its leavings to threaten Americans' freedom.

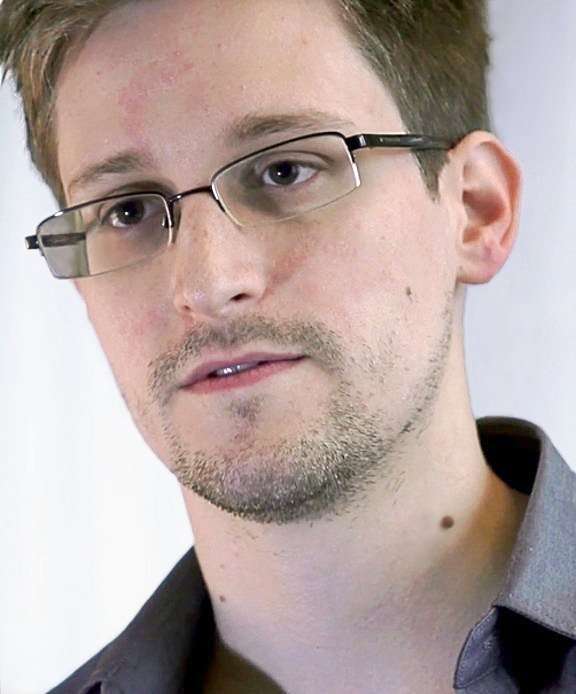

Earlier this year, CNN's Jake Tapper pointed out that the Obama administration, after bringing charges against Edward Snowden, "has used the Espionage Act more to go after whistleblowers who leaked to journalists not just than any previous administration, but then more than all previous administrations combined." The claim was subsequently endorsed by PolitiFact as "true." That's a shocking use of government power to punish those who would call government officials out for their misbehavior, but hardly an unaccustomed role for for a law passed during World War I and quickly used to muzzle critics of official policy.

In fact, the "war to end all wars" left a legacy of government dominance and intrusive power in its wake that officials still exploit, and from which the country continues to suffer.

In its original form, the Espionage Act was used to prosecute Robert Goldstein for producing a movie about the American Revolution. The U.S. having recently allied itself with Britain against Germany, Goldstein's historically rooted portrayal of British soldiers as the bad guys was considered an attempt to hobble the war effort. He served three years in prison for his cinematic labors.

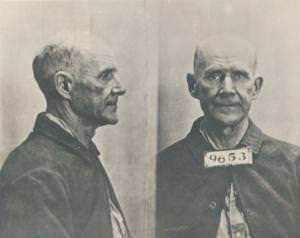

Repeat Socialist presidential candidate Eugene Debs (pictured) was charged under the Espionage Act for speaking against conscription and the war. His health broken in prison, he was finally freed by President Warren G. Harding in 1921.

Joseph Franklin Rutherford and other leaders of what became the Jehovah's Witnesses were imprisoned in 1918 for publishing a book that criticized patriotism. Their views were considered dangerous to efforts to satisfy the government's new appetite for patriotic young military recruits.

These days, the amended Espionage Act is no longer used to stifle speakers, writers, and moviemakers (the provisions criminalizing "sedition" were repealed in 1920). Instead, it's used as a weapon, or just a threat, against those who would disseminate inconvenient information to the press and the public.

In addition to Snowden, who was charged for revealing details of the government's vast surveillance efforts to Glenn Greenwald and other journalists, the Espionage Act was used to penalize Thomas Drake, who blew the whistle on wasteful and illegal snooping activities at the National Security Agency. He pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor in 2011 to avoid lengthy prison time.

John Kiriakou, a former CIA analyst who awkwardly confirmed that the U.S. tortured terrorism suspects before President Obama was ready to concede that "we tortured some folks," was charged under the Espionage Act. He is currently serving 30 months in prison.

This follows in the example set by the 1971 prosecution of Daniel Ellsberg, a former military analyst who was the first whistleblower charged under the 1917 law after leaking the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times.

The Espionage Act is the most visible stain left on the national character by the First World War. But it's not the only one. If civil liberties eroded during the war, economic freedom did, too.

The War Industries Board was established in 1917 to coordinate the government's acquisition of supplies for waging war in Europe. This rapidly turned into, in the words of Wilson administration official Grosvenor Clarkson, "a system of concentration of commerce, industry, and all the powers of government that was without compare among all the other nations, friend or enemy, involved in the World War."

At the same time, Herbert Hoover became "food dictator" (a term he himself used) over the United States Food Administration. The new agency had the power to regulate the distribution and use of food. It rapidly extended that power to control the price that people could charge for meat, produce, and other goods.

A counterpart, the Federal Fuel Administration, exercised similar powers over the distribution of oil and coal, controlling both price and use.

The end result was an unprecedented degree of government control over the economy. That intervention also created a class of bureaucrats accustomed to exercising such dominion—and a constituency among big businesses that benefited from powerful connections, assured markets, and the suppression of competition.

When the Great Depression descended on the country in 1929, now-president Hoover was already accustomed to invoking his wartime experiences as a model for dealing with the country's economy. "An infinite amount of misery could be saved if we have the same spirit of spontaneous cooperation in every community for reconstruction that we had in war."

The New Deal imposed by his successor, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, largely built on the wartime policies of which Hoover had been an architect, and the precedents and culture established by the expanded state of the First World War. While the corporatist policies of the 1930s have retreated, the proliferation of boards and bureaucrats wielding vast economic power never entirely went away. Depression-era farm subsidies continue to distort food production and hike prices in the United States, damaging the environment and enriching the well-connected.

America's involvement in World War I lasted just a year and a half. But government today uses its leavings to choke off the free flow of information, goods, and services, and to threaten Americans' freedom in the process. The Espionage Act lingers on, as does the habit of government meddling and intervention in the economic affairs of private businesses and individuals.

Just a few short and bloody months of conflict, and a century later we're still dealing with the damage done to our freedom.