Buying Out of Socialism

The Thatcher administration has found a sure-fire way to reduce big government—sell it to the people.

Peter Haskell, union member and lifelong supporter of Britain's Labour Party, has had a change of heart. In the last election the retired postal worker voted for the Conservative Party for the first time in his life.

Haskell wasn't converted by the force of Margaret Thatcher's personality, nor was some particularly cogent Conservative Party position paper the key. In fact, ideology had nothing to do with it. The Conservatives won his vote the old- fashioned way: they bought it.

They bought it by giving Peter Haskell and his wife the chance to buy their own home rather than spend the rest of their lives in government-owned public housing. And they bought it by allowing Peter Haskell, Labour Party stalwart, to become Peter Haskell, stockholder in communications giant British Telecom.

There is nothing illegal or unethical about this Conservative strategy. It's just good politics. And in the process of buying off Peter Haskell and hundreds of thousands of other working-class voters, the Thatcher government is shrinking the size of Britain's massive welfare state and turning traditionally socialist constituencies into enthusiastic capitalists.

Privatization—turning nationalized industries over to the private sector, by hook or by crook—is revolutionizing politics and everyday life in Great Britain. Consider the evidence:

• In six years, the government has sold 873,000 public-housing units to their tenants. That's 13 percent of Britain's public housing.

• British Telecom, the huge government-owned telephone and telegraph company, was sold to the public last November. It was the largest public offering of stock in history. Two million Britons, about half of them first-time investors, bought shares.

• The government has sold all of its stock in British Petroleum and has sold off subsidiary operations of British Steel, British Rail, and British Airways.

• Slated for privatization before the end of 1987 are National Bus, Rolls Royce, British Airports Authority, British Gas Corporation, and four other large state-owned firms.

• Every city and town in Britain has contracted out at least one service to private firms. At the current rate, there is a local service, from collecting garbage to cleaning school windows, being privatized every day.

It all adds up to a dramatic change from the recent past. In the 18th century, Scottish philosopher and economist Adam Smith described Britain as "a nation of shopkeepers," dedicated to free trade abroad and competition at home—and to innovative products, new markets, and an unfettered economy. Following World War II, however, economic liberties gave way to socialism under the leadership of successive Labour Party governments. One by one, the once proud and unbeatable British industries fell to nationalization. Eventually the British economy, burdened with anemic and uncompetitive nationalized industries, went into a tailspin. By 1979, the once robust British economy provided one of the lowest standards of living in Europe.

When Margaret Thatcher assumed the office of prime minister in 1979, nationalized industries accounted for a full 10 percent of the gross domestic product. The government dominated the fields of transportation, energy, communications, steel, shipbuilding, and health care. More than 1.5 million Britons worked in state-owned firms. The economy was on the ropes.

Had Thatcher pursued the usual Conservative strategy—advancing cautious reforms of the welfare state and trying to introduce new efficiencies in the public sector—her tenure would be a footnote in the textbooks. Instead, she chose radicalism and as a result may well have changed the course of Britain's history. Already, 400,000 jobs in 16 different companies have been moved to the private sector and 7.7 billion pounds funneled into the British Treasury, and the government plans to continue selling at the rate of about 2 billion pounds a year.

Before telling you how Margaret Thatcher did it, I ought to confess my role in all of this. The Adam Smith Institute is a British free-market think tank that has acted as a fount of ideas and a behind-the-scenes advisor in Thatcher's privatization campaign. We've had varying degrees of success. Some proposals have been adopted on the spot; others have been dismissed. Some survived bitter, protracted fights in the halls of Parliament, while others have been modified or diluted before being enacted.

Economists have known for a long time the efficiencies that are characteristic of private versus state enterprises. Political theorists have argued eloquently for the enhancement of individual liberties under private versus government activity. But this is not enough.

In the process of trying to nudge privatization along in Britain, we have learned—and helped government officials sympathetic to privatization understand as well—that before any state-owned or state-directed activity can be "hived off," as we say over here, you must satisfy four special interests. They are, in no particular order, management, the workforce, the public, and legislators. Success demands that you devise a method of privatization such that the transfer will be in the best interest of each of these groups. Ignore this bit of advice, and even the most sensible plan will remain forever on the drawing board.

So there is no single best method of privatization. We follow this simple rule of thumb: If you can sell, sell it. If you can't sell the whole, sell part of it. If you can't sell any of it, give it away. And if you can't give it away, contract it out. Almost any government program can be turned around in this manner.

In 1984 the Blackwell Corporation, producers of the PBS television series American Interests, came to Britain to chart the course of the British move to sell off the state. Reporters talked to workers, business executives, and politicians of all stripes. Drawing from that report—"An Economic Miracle in the Making"—and from the Adam Smith Institute's own research, I've put together for American readers some of the most interesting case studies to show how your transatlantic friends are going about devouring the state.

Kicking Out the Landlord

When Thatcher took office, the government owned about 35 percent of all the housing in Britain. More than one of every three Britons lived in a state-owned house (called "council houses").

The housing issue had been a sure-fire loser for the Conservative Party every time out. In the two decades prior to Thatcher's rule, they insisted that public housing pay for itself—that is, they proposed to raise the woefully inadequate rents to cover costs. Year after year, public-housing rent increases were a fixture of the Conservatives' platform, and year after year they lost. Labour was saying, "Vote for us and we'll keep your rent cheap." The Conservatives were saying, "Vote for us and we'll raise your rent." Public-housing tenants, being rational individuals, flocked to Labour.

There had to be a way to break this impasse. In 1979 the Adam Smith Institute proposed that the government simply give public houses to the tenants. This would have been a good deal for the government, since it was losing money on the houses anyway. But the idea struck the Thatcher administration as too radical. It did adopt a similar scheme, however—the right to buy at greatly reduced prices. Legislation was passed enabling tenants to buy their homes at prices up to 50 percent below market value, the discount depending on how long they had lived in the house.

The program has been a smashing success. During the last six years, 873,000 public houses have been sold to private individuals, raising more than 5 billion pounds for the Treasury. This has been the largest single transfer of property since the dissolution of the monasteries by King Henry VIII in the 16th century.

Perhaps most dramatic has been the change in the attitudes of the new homeowners. American Interests TV reporters found that Wandsworth, for instance, a middle-class inner borough of London, has been completely transformed by the program. Once a shoddy, ill-kept neighborhood, it has become a sharp community of fresh paint and manicured lawns. As Wandsworth resident Peter Haskell admitted on camera: "To be honest with you, when you own a house you look after it more. You not only look after your own part, you also look after the surroundings as much as you can.…Obviously, you know, we try to keep it tidy as much as we can."

Between a third and a half of Wandsworth's public-housing residents have bought their homes. It's not difficult to determine which houses are privately owned—as Haskell observed, "you can tell by alterations in front where people have done their doors—new doors, new windows, you know."

The housing policy has reinvigorated the Conservative Party, as well. In the last election, Labour again promised, "Vote for us and we'll give you cheap rent." But this time the Conservatives countered, "Vote for us and we'll give you cheap houses." The voters' answer should be obvious.

There is a postscript to this story: Labour opposed the sale of houses from the start. Labour-controlled local councils resisted the program until Conservatives enacted "right to buy" legislation, and Labour politicians even threatened to take the houses back into state ownership if they returned to power. But even politicians can learn simple lessons. In April 1985, the Labour Party unveiled its new housing policy: Public housing tenants shall have the right to buy their homes.

Owners in the Drivers' Seats

Nothing concentrates the mind like the imminent threat of "job separation." In 1979, Thatcher announced her intention to privatize the National Freight Corporation (NFC), Britain's largest trucking firm. To NFC's executives, the news couldn't have been worse. The company would likely be sold to a competitor, and top management would likely find themselves standing in the unemployment line.

In their desperation, National Freight's management came up with a plan—an employee buy-out of the company. The workforce was immediately skeptical; management faced an enormous selling task. Since the average man in the street in Britain had never owned stock, recounted NFC Chairman Sir Peter Thompson, "We had to start by explaining to our drivers what exactly a share was. It was a huge exercise in communication." But in the interest of saving their own jobs, NFC's management had become leading advocates of the privatization!

The campaign worked. The workers were persuaded that an employee buyout was in their own interest, and 25 percent of the workforce (10,000 workers) invested some 6.2 million pounds. (The average worker-stockholder bought 700 shares at one pound each. By early 1985, each of these shares had surged in value to 7,000 pounds.) National Freight's workers bought a full 83 percent of their company, the rest of the financial backing coming from British banks. It was the largest employee buy-out in British history.

On February 22, 1982, Sir Peter Thompson went before the workforce to announce NFC's new incarnation as a private, employee-owned company. "Today is a tremendous day," exulted Thompson. "We have got a new slogan: 'We're in the driving seats.' It is a simple concept. Let's own and control the company we work for."

Since the buy-out, NFC reports that employee productivity has increased by 30 percent. And, as with housing, workers have learned that private property and free markets are a good deal for everyone. Steven Shepherd, a driver with NFC who bought stock the first day it was offered, muses, "You realize that part of this truck—it might only be very small now—is your money, you know, and it gives you that new edge."

Employee Peter Finnell, who joined the company and bought in with stock after privatization, says, "It's nice to see all the board sitting up there on the rostrum at the shareholders' meeting, and they are only there because you put them there, no one else. You are the shareholder."

A Nation of Stockholders

In the spring of 1984 Margaret Thatcher took on perhaps the biggest challenge in her privatization program. British Telecom (BT), the world's fourth-largest telephone company, was put up for sale. Skeptics said she was needlessly risking the success of the entire program and of her administration, as well. But Maggie pressed on.

As with earlier privatization battles, selecting the proper strategy was crucial. Buying off the management was simple—the government permitted BT's managers to steer the public-to-private transfer, thus trading their positions as bureaucrats at a state monopoly for new status as executives of a powerful and profitable private firm.

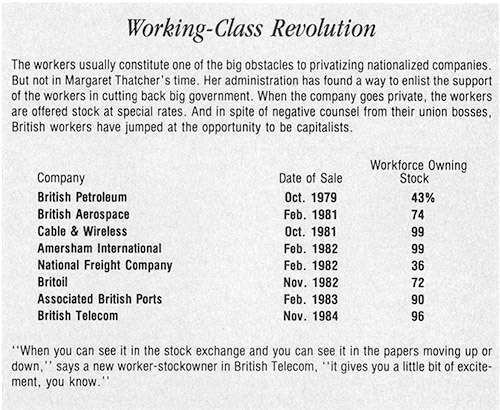

Getting the support of BT's workers was more difficult. Union leaders and Labour Party officials were telling them to resist privatization. But the workers, mindful of the success of previous transfers such as National Freight and caught up in the excitement of a $20-million media campaign to sell BT stock to the British public, ignored the advice of their putative leaders. In the end, 96 percent of BT's workers bought stock in their company.

The real story of BT, however, was the success the company had in convincing the general public to buy stock in this poorly run, much-maligned firm with a reputation for efficiency approximating that of the US Postal Service. Sleek, jazzy ads proclaimed BT "the power behind the button." BT's management stumped the countryside for support from stockbrokers and ordinary blokes. Ads were geared to small, first-time investors, and purchases of the original stock issue were limited to 800 shares to ensure that big institutional investors couldn't gobble up huge chunks of stock until the little guy had bought his shares. British Telecom even offered reductions on telephone bills for three years to stockowners.

When BT went on sale in November 1984, the reaction was frenzied. Shares opened at 50 cents and rose to 97 cents within hours. At day's end, two million people had become stockholders, doubling in a single stroke the number of Britons who own stock. Overnight, British Telecom had become the nation's largest private company.

BT's chairman of the board, Sir George Jefferson, told American Interests reporters, "I think (the sale) is the biggest impact, really, since the war in this country. This has really caught the public imagination, and those people are staying with us."

It has indeed caught the public imagination. Allen Partington, a warehouseman, is a typical new stockowner. "If I go to a bank and invest the money I intend to put with BT, I will get six percent, 7 percent. It is not exciting. But when you can see it in the stock exchange and you can see it in the papers moving up or down, it gives you a little bit of excitement, you know, and I really enjoy that."

Sleek, Sporty, and Private

In Britain, even the automobile industry has long been seen as a fit province for government ownership. But in 1984 Thatcher succeeded in privatizing the luxury-car maker Jaguar, which was nationalized in 1966 and had spent the last 18 years as a division of state-owned British Leyland.

By the time Jaguar came on the market, privatization had become a household word in Britain. Traffic jammed London streets as people lined up to buy shares the day Jaguar stock was offered to the public. The television news pictured gentlemen in bowler hats bashing each other with briefcases and umbrellas in the mad dash. Nearly 190 million shares were purchased.

In the first year after privatization, Jaguar's before-tax profits nearly doubled. Worldwide sales increased 15 percent. The improvement, Jaguar chairman John Egan believes, is attributable to the competitive pressures of private enterprise. During the 1970s, he explained, while Jaguar was state-owned, management pursued economies, not excellence, in its cars. Yet luxury cars are valued precisely for that excellence: for being the fastest, the sleekest, the most beautiful.

When the threat of failure no longer hangs over a business, as is the case when the state owns a company and can make up its losses by simply increasing taxes, management has no incentive to please consumers. "The real basis of business in a democracy is that you make profits out of satisfying customers," observed Egan, "and these were things that the nationalized industries never really sought to do."

If You Can't Give It Away…

In 1812 the British government appointed a man to sit with a telescope on the Cliffs of Dover, overlooking the English Channel, and watch for Napoleon's fleet. If he saw it, he was to light a beacon so that other beacons could be lit, thereby alerting London of an imminent French invasion. Well, Napoleon was finally exiled to St. Helena in 1815. He died on May 5,1821. But the office of invasion-alerter survived until 1948.

This story proves that unnecessary programs can be eliminated. It's very difficult, though. There are no unnecessary programs in the eyes of their beneficiaries or their administrators.

Take, for example, Britain's public steam laundries and bath houses, built in the Victorian era to give citizens an opportunity for bathing and cleaning. A few years ago, the city council in Edinburgh tried to close the government-subsidized laundries, in view of the fact that most homes now have washing machines and there are coin-operated laundries everywhere.

The attempt failed utterly. Women appeared before the council pleading poverty. Sociologists testified that the laundries provide the women important social interaction with their friends. Penologists suggested that juvenile delinquency would rise because of added stress on the women. It was even suggested that there would be a serious risk of disease epidemics. Naturally, the city council gave in. How foolish they'd been to identify this as an unnecessary program!

What, then, can be done about local government services that are a drain on the taxpayer? The traditional Conservative Party proposal has been to charge fees for the use of these services. Where it's been tried, however, it's proven to be universally disastrous. It doesn't work because charging user fees has a political cost.

Someone has to set the charges, and there is every pressure on that person or persons to set them as low as possible and, conversely, to set the size of the government subsidy as high as possible. When it comes time to renegotiate those charges, city officials come under intense pressure from organized lobbies. If the officials try to charge fees reflecting true costs, they're portrayed as being somewhere between Scrooge and a Victorian poor-house manager. Sound economic principles can be protected only by putting the best legislators at political risk.

Council housing is an apt example. In the decades after World War II, a small gap between rents charged and costs incurred grew increasingly wider. There was every incentive for local politicians to buy votes from renters by keeping rents cheap and to extract the true cost from taxpayers at large. That's why it would have paid the government, by the 1980s, to give away the houses, although the Thatcher administration struck a better deal.

In the case of public services, there's no individualized benefit such as a council house to offer to the voter to buy off his interest in continued government subsidization. So the Thatcher administration has resorted to the final stratagem in the four-step privatization chain: "If you can't give it away, contract it out"—have the public services performed by private businesses under contract to city government. The financing of the service is kept in the public sector, but the actual provision of the service is done by a private company.

Contracting out works politically because it doesn't eliminate services. And it works strategically because it saves the taxpayers money. Because there is competitive bidding, the private company providing the service under contract faces constant pressure to keep costs down and quality high. The policy saves local governments far more money than was ever saved by attempting to raise user fees.

One of the first city councils to try contracting out was the London suburb of Southend. Armed with studies from the Adam Smith Institute showing that considerable savings would result, in 1980 the Southend city council invited bids from private companies for garbage collection and street cleaning.

The predicted cost cutting ensued. "Neighboring city councils were shocked when they heard of the size of our savings,'' recalls one council member. "We immediately knocked more than 20 percent off our cleaning budget."

Other cities soon followed suit. Today there isn't a single city service in Britain that isn't a candidate for privatization—from pest control to legal services, from grass cutting to restroom cleaning.

Alas, the labor unions have always opposed privatization. It's easy to understand why: Nobody likes giving up his monopoly. Last year British unions earmarked 1.5 million pounds to campaign against privatization, an amount roughly equal to the savings to a medium-sized city from contracting out its services.

Even here, though, Labour may be learning a lesson. Interestingly, many Labour-controlled city councils have joined in the move toward contracting out. And many local Labour Party groups, who initially opposed privatization, have not reversed the trend when they regained power.

Is Nothing Sacred?

Sometimes, the constituency whose feathers will be ruffled by eliminating a government service is so small that it can be axed with impunity. This has been the case with some of Britain's QUANGOs. These are not some new member of the marsupial family. Rather, QUANGO is an acronym standing for quasi-autonomous nongovernmental organizations, which are similar to US regulatory agencies.

Six years ago, there were 3,058 QUANGOs in Britain. Among them, for example, were three related to birds: the Advisory Committee on Bird Sanctuaries in Royal Parks, the Advisory Committee on the Protection of Birds in England, and the Advisory Committee on the Protection of Birds in Scotland.

The Adam Smith Institute advised the government that the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, a private organization, was doing more to protect our feathered friends than all three government organizations put together. The Royal Society consistently gave better advice and obviously was more dedicated to its purpose than were the government-paid bird watchers. The government took our advice, transferred the care of bird sanctuaries to the private group, and abolished the three bird QUANGOs.

The existence of the most absurd QUANGOs was of invaluable help in generating public support for reducing the scope of government power. Drawing attention to such bizarre life-forms as the Inspector from the Ostrich and Fancy Feather Council and the Inspector from the Artificial Flower Wages Council helped curb some serious QUANGO abuses of power, such as harassment of small businesses.

So far, 600 QUANGOs have been privatized or abolished. Yet 2,400 remain. And other elements of Britain's massive state have hardly been touched.

The crown jewel of the British welfare state, the National Health Service, is seemingly sacrosanct. The government has instructed NHS hospitals to invite bids from private businesses for their catering and cleaning services, which will certainly save a nice sum of money. But Britain's bloated socialized healthcare system lumbers on, unimpeded by the vigorous fresh air of competition.

Britain's social security system is slightly closer to reform. Thatcher has instituted a contracting-out option for the smaller, second tier of the system, the State Earnings Related Pension System, but the basic pension all Brits receive from the government is so far beyond the pale of political debate.

We still have a long way to go. The good news—for consumers and taxpayers, workers and managers, ordinary and enterprising alike—is that privatization in Britain is now probably unstoppable. Too many people have derived advantages from it. People like having their services provided more cheaply. They like having choice. They like paying lower taxes because state services no longer consume massive subsidies. They like owning a piece of this and that highly visible British industry. They like being capitalists.

And they'll have more chances. Now scheduled for private transformation are British Gas, British Airways, and the British Airports Authority. Rolls Royce and British Nuclear Fuels are coming up soon, and the water utilities are under discussion. The chairman of the state-owned electrical utilities corporation has called for his industry to be put on the market.

Six years ago no one, not even those of us who were hammering out privatization strategies at the Adam Smith Institute, dreamed that the British state could be rolled back as far as it has. Nor would anyone, least of all the putative representatives of the workers, have predicted that the working class would be an important new constituency in this battle to restore capitalism. But it has—and that may be the most revolutionary legacy of Margaret Thatcher's Conservative administration.

Madsen Pirie is the president of the Adam Smith Institute in London and the author of Dismantling the State (Dallas, Texas: National Center for Policy Analysis), which analyzes 22 different techniques employed in Britain's privatization effort.