Saving the Wilderness: A Radical Proposal

Will the need for strategic minerals spell the death of America's wilderness? Environmentalists think so-and defense-minded congressmen are reinforcing those fears. But there is a way to have our minerals and keep our wilderness too.

The free enterprise system as it works in practice excludes [some] goals. Does anybody believe the mining and chemical companies are going to keep the water and air clean without a hard shove from government?

—Joseph Kraft,

syndicated columnist, April 1981

You better believe the oil companies behaves themselves on Rainey.

—Lonnie Legé, manager,

Rainey Wildlife Sanctuary

Marshland, like the desert, does not appeal to everyone. Swamp is not a word that conjures up visions of beauty in everyone's minds, but for some, Vermilion Parish in Louisiana is the most beautiful place in the world. If you don't mind the mosquitos, you can take a boat into the flat, wet land of the Cajuns to see a part of the world that is hauntingly alluring. If you take a shallow-bottomed bateau into the marsh on a winter morning before the sun rises, there is much beauty.

Mist obscures the horizon as the traveler navigates around locust, cypress, and clumps of roseau cane. As the morning light increases, the startling colors of marsh flowers—fiery orange and yellow and dry bone white—become noticeable. Deer run wild where the bayou turns to firm ground. The predawn light might reveal armadillo, muskrat, otter, mink, nutria, or any one of hundreds of different birds that love the marsh or the alligators that seek out those "critters," as the Cajuns say, for breakfast.

But the real show doesn't start until the sky turns lavender with the rising sun. The sun through morning fog is the signal for thousands of snow geese to prepare for flight. Flexing the muscles of their wings, the birds begin to whip the air. Tens of thousands of small thuds turn into a thundering of goose wings, yet they remain on the ground. Finally they lift off. Their honking adds to an already almost overpowering noise as squadrons of geese launch and take up flight formation. On some mornings the sky may fill with 20,000 snow geese; on others there are an awesome 60,000 geese in the air, blanketing normal conversation.

When the morning flight ends in the National Audubon Society's Rainey Wildlife Sanctuary, a visitor may decide to take the long way home and see more. The sanctuary is and has been a haven for many different species, stringently protected from the human species; even tourists are not welcome in the Rainey preserve. But journalists with the right credentials may take an escorted tour into the marshland to see one of the most startling sights on the whole preserve. Leading you down the right bayou, through the right swamp land, around the nesting grounds of beasts both fur and fowl, the Cajun guide can bring you to man-made islands of steel and concrete: natural gas wells.

Gas wells in terrain managed by professional, dedicated environmentalists may seem almost as out of place as free drinks at an AA meeting. What happened to the hostility that has come to exist between resource developers and conservationists? Have the lion and the lamb laid down together in the same field?

On the national front, nothing could be further from the truth. Ever since Reagan was elected president—and especially since he appointed James Watt secretary of the Interior Department—environmental groups have been concerned that their victories of the '60s and '70s will be reversed. And industry voices, counting on a sympathetic ear, have stepped up their complaints that pro-environment resource and antipollution policies are hamstringing the US economy.

Now, the battle is moving to the strategic metals front. Citing the economy and national security, some people are pointing with alarm to America's growing dependence on unstable or antagonistic foreign sources, not only for petroleum, but for many minerals, as well. In 1980 Rep. James Santini (D-Nev.) held hearings on the strategic metals situation in his Mines and Mining Subcommittee. He also urged the Interior Department to study the problem, but its report, with a recommendation that domestic production be stimulated, was a source of embarrassment to President Carter. After an unsuccessful attempt to get Interior not to release its report, Carter ordered a National Security Council review, not yet completed, of US minerals dependence.

The Reagan administration, however, came into town with definite ideas about the situation. From his confirmation hearings on, Interior Secretary Watt has laid emphasis on forming a federal policy toward strategic metals. (The executive has been enjoined by Congress to do this since the Mining and Minerals Policy Act of 1970 was passed, but it has never done so.)

The first prong of such a policy, Watt has made clear, is to make public lands more accessible to mining. And that worries those who would have portions of the country preserved and protected as wilderness. "Interior Seeks Government-wide Policy; Environmentalists Fear Mineral Raids on Public Lands"; "Sides Square off over Hayakawa's Wilderness Development Bill"; ''Reagan's Drive to Open More Public Lands to Energy Firms May Spark Major Battle"—these have not been unusual news headlines in the past few months.

But the gas wells in the Rainey Wildlife Sanctuary may be the answer in microcosm to the confrontation now coming to a head. The significance of the Rainey wells may not be obvious at first, but it is our belief that they point the way to a solution both for those who fear that America is courting disaster by keeping crucial minerals locked away because of environmental concerns, and for preservationists who fear that their hard-won gains may be swept away in the face of a national minerals shortage.

The anxiety of those on the pro-development side is based on the fact that the United States is largely dependent on foreign sources for natural materials that enable people to travel, receive medical care, be entertained, or even work at the jobs that provide money for groceries. Even agriculture, dependent on machines and transport, would be drastically affected by a cut-off of mineral supplies.

Ever since the Arab oil embargo of 1973, the possible cut-off of petroleum to the United States has been the inspiration of conjecture about military intervention overseas in the case of another stoppage. Yet imports account for less than half of America's oil consumption.

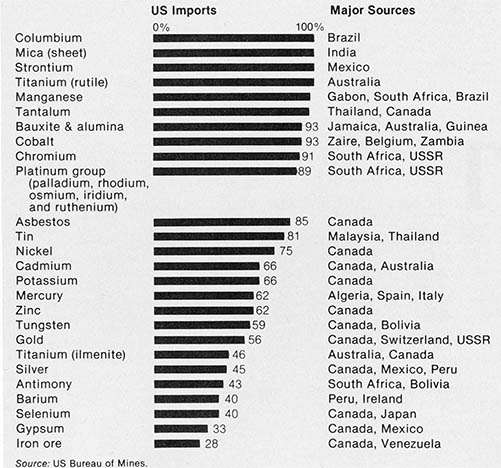

By contrast, imports account for from 70 to as much as 100 percent of at least a dozen minerals essential to US industry. More than 50 percent of half a dozen other essential minerals come from foreign sources. (See box, p. 31.) Observers grow even more edgy when examining the particular sources of crucial metals—mostly the Soviet Union and southern Africa. With the exception of Australia, which has a limited potential for increased export, most of the foreign sources are politically unpredictable.

The major deposits of chromium, for example, are in South Africa, Zimbabwe, and the Soviet Union. Allen Gray, technical director of the American Society of Metals, warns, "A cut off of our chromium supply could be even more serious than a cut off of our oil supply. We do have some oil, but we have almost no chromium." In fact, the United States imports 91 percent of its chromium. If it were not available for transformation into stainless steel, surgical equipment, and ball bearings, the American way of life would take a quick and nasty turn.

The possibility of economic disruption of serious proportions is one source of increased activism by those who would like to ensure prosperity for Americans. If the use of foreign minerals in American industry were to diminish slowly, there would be a gradual realignment of prices and products. But a sudden cut-off would not allow for gradual readjustment, and chaos becomes a word with legitimate function.

Also disconcerting to many, however, is the effect a minerals shortage could have on national security. Jet aircraft and high-technology components of military hardware are particularly dependent on minerals supplied largely from Communist-controlled or politically unstable areas of the world.

For those who would welcome the implications for the US arms build-up, however, there is little consolation in the minerals situation. As long as the government considers an uninterrupted flow of resources worth fighting for—and that is a good part of the rationale for the Carter-initiated and Reagan-embraced Rapid Deployment Force—there is danger that the American military will ''secure our vital interests" in case of an interruption of that flow. Members of the defense community warn that in the event of a "minerals war"—the strategic denial of minerals to the United States by foreign powers—the United States could not maintain "limited warfare" for any extended period of time. The inference is that the only option outside of surrender would be "unlimited warfare."

Is the problem that US sources of strategic minerals have been depleted by previous mining activities? On the contrary, contends John P. Morgan of the US Bureau of Mines, who says that "the U.S. could be virtually self-sufficient in all but a few minerals, such as chromite." His opinion is shared by many, including Sen. Harrison Schmitt (R-N.M.), a geologist and former astronaut. "Nature endowed us with unbelievably vast natural resources," he notes, "most of which have not been tapped."

In its report at the conclusion of hearings on strategic minerals, Representative Santini's subcommittee pointed out several factors that have contributed to the increasing foreign share of US mineral supplies: US tax policies that fail to encourage capital formation, health and safety regulations that increase the cost of production, antitrust legislation that is supposed to encourage competition but actually discourages mineral production, and restrictions on or prohibition of mining on federally owned land. It is the latter—what Santini's report calls the public land access problem—that is now the focus of hot debate and that is our concern here.

The federal government owns one-third of the land area of the United States, and it happens that much of that acreage is concentrated in mineral-rich states. Alaska is 89 percent federally owned; Nevada, 86 percent; Utah, 66 percent; Idaho, 64 percent; Oregon, 52 percent. A 1977 Interior Department report estimated that 42 percent of public lands have been declared off-limits to any mining for minerals and that mining activity has been greatly restricted in 16 percent and moderately restricted in another 10 percent. Santini's report estimates that further withdrawals of land since 1977 have made those figures 10-15 percent low, with the prospect of more withdrawals under the National Wilderness Preservation System and other federal programs. This is the vast acreage that Interior Secretary Watt has vowed to open up to mining activity under "a national strategic minerals policy…that protects American jobs and investments, improves our balance of trade, revitalizes the nation's economy, and provides for the security of foreign minerals imports."

Lined up against Watt and the industries whose interests he is charged with serving are people who have fought hard to have the government preserve large portions of American land in pristine or near-natural states. Historically, they are latecomers. There was so much wilderness land around until the last century that few thought of undeveloped land as an asset. Aside from occasional and largely transitory disturbances of the land by Indians, the vast bulk of what is now the United States was pristinely primeval. While it may have been heaven for Druids, however, given the tools of the day it was hell for settlers.

When Tocqueville was traveling on the fringe of civilization and announced his desire to venture into the primitive forest for pleasure, the frontiersmen considered him insane. Many of those who did daily battle with nature had grown to hate and fear it. Wilderness was something to be subdued to make way for civilization.

The writing of this period is permeated with the association of wilderness with evil. On the eve of settlement Michael Wifflesworth wrote that the new land was a "wasting, howeling wilderness,/Where none inhabitants/But hellish fiends, and brutish men/That devils worshiped." The idea of wilderness as enemy persisted long after the pioneering way of life was over, until, during the 19th century, a more favorable approach began to take hold.

Throughout our history, wilderness has been an unpriced asset. Initially, there were no charges to its users because it had a negative value. Today, there are no charges despite its positive value. When the majority of land was wilderness, the marginal value of an incremental unit was zero or negative. Its primary value lay in being able to convert its resources into marketable products. Only to Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, John Audubon, and a few others who were considered eccentrics did wilderness also have value as a good to be enjoyed in and of itself. Today, their appreciation of wilderness is shared by many more, yet there are no charges to its users despite its positive value.

As incomes rose in the United States, so did the amount of time Americans spent on recreation. This trend is accelerated by an increasing marginal tax rate on earned incomes—the more money you make, the smaller the part of it you get to keep. A logical reaction is to increase the use of resources that have no direct user fees for the consumer. Those who use wilderness for recreational or aesthetic purposes are not charged for or taxed on the benefits they derive from it.

Along with the increased recreational demand for wilderness, however, there was an increased demand for land for other uses. Thus some of the supply of wilderness was being withdrawn at the same time as demand for it was increasing. Both of these factors acted to increase the value of wilderness. Obviously, rare wilderness ecosystems would demand a high price if they could be owned and exchanged like other goods.

But they can't. By 1950, many of the areas we could consider wilderness were already public land and thus not available for sale. But this meant that wilderness lovers could not keep such areas away from other users simply by outbidding them in a market. Instead, the increasing value of wilderness generated a movement to save it via the political process.

For politicians, it was an ideal situation. Because the areas were not privately owned, condemnation proceedings with their attendant costs were not required. Land could be set aside for users of wilderness as wilderness simply by congressional designation.

Probably the first suggestion in the United States that land be set aside as wilderness was made in 1833 by George Catlin in a letter published in a New York newspaper. In 1844 New York State created a forest preserve by constitutional amendment, and in 1872 Yellowstone National Park was established. The idea that wilderness should be protected was beginning to gain support. By 1933, 63 primitive areas had been established on Forest Service (Department of Agriculture) land, ranging from 5,000 to over 1 million acres.

With passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964, 9.1 million acres of land were protected from development—including any and all mining activity—and the Forest Service was enjoined to recommend further areas for congressional designation as wilderness. Section 2(c) of the act defines wilderness as

an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain. An area of wilderness is further defined to mean in this Act an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its primeval character and influence, without permanent improvement or human habitation, which is protected and managed so as to preserve its natural conditions.

The section specifies that wilderness must show no substantial mark of man, provide opportunities for solitude and primitive recreation, and be of at least 5,000 acres and may (but need not) "contain ecological, geological, or other features of scientific, educational, scenic, or historical value." In 1976 the Interior Department's Bureau of Land Management (BLM) was brought into the recommending process. By 1980, a total of almost 80 million acres had been set aside as wilderness.

In addition, 62 million acres being considered for wilderness classification under the Forest Service's Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE II) process must legally be treated as wilderness until RARE is completed and Congress has acted on any recommendations (Congress has as much as 11 years to do so). Likewise, 60 million acres in the comparable BLM program have been set aside as Wilderness Study Areas. In sum, though many environmentalists worry that there is not enough land designated as wilderness, the total is hardly trivial.

Given the history of government as protector of the environment, however, it is not surprising to see environmentalists concerned about the Reagan administration's promise of stepped-up development of public lands under BLM supervision. For years, government has failed to act as the protector of individual rights against invasion of the body and destruction of property by pollutants. Only recently has it begun to stop gross violations of rights occasioned by the "externalities" or waste products of its own and business activities. One need look no further than the pollution of the Great Lakes or the cancer-ridden communities in Utah that were subject to atomic tests by the American military. Moreover, government powers of eminent domain and taxation have been used to build railroads, dams, pipelines, and nuclear plants where they may never have been built if developers had been left to pay the full costs of moving people off land desired for projects and if the actual users of projects had been required to pay for the costs of development.

Nor has government's management of publicly owned resources provided examples of enlightened stewardship. Whether the strategic minerals situation is brought to a head by an actual emergency or by the threat of one, it is clear that, as long as the bone of contention is access to public lands, government will decide how mineral exploitation will be carried out. That could be, in common terms, bad news. Theoretically, we would predict as much, but actual examples of what has come to be known as the "tragedy of the commons" are more helpful in understanding the problems with government ownership and management of resources.

Wilderness advocates would do well to examine the fate of the American bison. While cattlemen in the old west jealously guarded and improved the quality and size of their herds, buffalo were being slaughtered for their tongues because, since no one owned them, no one had the incentive (the possibility of reaping benefits in the future) to protect them. Whale populations have suffered because of the same lack of clearly defined and enforceable property rights.

The timber industry is criticized for logging ecologically sensitive areas. The very fragility of those areas, however, guarantees that they would have remained untouched were it not for government intervention. Slow-growing, sparsely timbered areas are a no-win investment for companies that have to absorb the whole cost of logging. But, typically government helps them out. Here in Montana, for example, areas have been logged that nobody could have touched without government-built roads. Besides causing 90 percent of the erosion associated with logging in areas that may take decades to reforest, the roads cost the taxpayers—thousands of dollars per thousand board feet of lumber taken out of one area. The loggers sold that lumber for only about $42 per thousand board feet. Obviously, if they had had to pay for their own roads, they would never have logged in this area.

Also in Montana, the government recently hired a professional hunter to kill cougars that were supposedly killing livestock. Few of the ranchers in the area would have launched a massacre of that scale. There is a grudging respect for the wildcats, which rarely prey on stock unless they are injured or too old to make it in the wild.

On the other hand, there are examples of situations handled politically in this country—with dubious results—that are handled through a system of private ownership in other parts of the world—with admirable results. Scotland has no government agency to protect water quality. Yet its streams run as pure and clean as any of us would have American streams. How does it happen? Individual Scots have clearly defined and transferable (saleable) rights to the streams, so incidents of pollution or diversion constitute damage to individuals, not failure to meet government standards, and are treated as such in the courts.

Property rights make a difference because they provide an incentive to manage a resource—whether a forest, a herd, a stream, or a parcel of land—in such a way as to maximize the long-run return to the owners. Government-owned resources, in contrast, are subject to political (not owners') decisionmaking, which tends to be short-sighted. Current benefits and costs are more easily discernible by the electorate than are future benefits and costs, and the politicians respond accordingly.

The results of this sort of decisionmaking can be very significant. Economists refer to the costs to society of misallocation of resources as "opportunity" costs: when resources are used in any way, opportunities to use them in other ways are forgone. If the federal government were to declare the materials used to make this magazine "public" property for the sake of producing a consumer information pamphlet on the recreational benefits of Army Corps of Engineering projects, the opportunity cost to society would be the loss of this magazine.

In the case of wilderness designation, there are very significant opportunity costs. Because minerals are not extracted from protected lands, society pays the price of wilderness lands in terms of goods that are not produced and in higher prices for the goods that are produced. In addition, jobs that would be created with an increase in mineral resources never materialize. Likewise, there are opportunity costs to, say, allowing a resort to be built on wilderness land: some people will not now be able to enjoy wilderness, and jobs attendant to caring for that tract as wilderness will no longer be available. If wilderness users were charged, society would also pay a price in terms of higher user charges for the enjoyment of remaining wilderness areas.

While in the past two decades environmentalists have succeeded in making people aware of opportunity costs associated with the use of land, now people are becoming increasingly aware of the opposite costs. There is a very real danger that environmental concerns will be swept away in a rush to supply the United States with vital resources. That is certainly not our wish. In an ideal system, we would have the economic costs of any ecologically motivated action taken into account. But we would also have the ecological costs of any economically motivated action taken into account. Which takes us back to the natural gas wells on Audubon property. Has private ownership made a difference there?

The largest of the Audubon Society's wildlife sanctuaries is 10 miles south of Intercostal City, in Vermilion Parish, Louisiana. The 26,800 acres of marshland are a haven for migrating snow geese, which coexist with nutria, mink, armadillo, and alligators. The Rainey Wildlife Sanctuary is a superbly successful attempt to accommodate "the critters in the marsh," as the Cajun manager of the sanctuary, Lonnie Legé, says.

The sanctuary is run for the sake of the wildlife, especially the geese, and visitors are politely encouraged to visit other bird refuges with facilities for observation. If you do gain access to Rainey, you go into the swampland with Lege or some of his relatives. If you travel to the right place, you will see the facilities of three oil companies currently operating a half dozen gas-producing wells, bringing the National Audubon Society close to a million dollars of revenue a year in royalties. In another, drier, area of the sanctuary, you could see cattle grazing for a per head fee to the owners.

The inherent contradiction between the situation at Rainey and the pleas of environmentalists to maintain an increasing amount of pristine wilderness is sharply defined. An Audubon pamphlet speaks calmly of the situation. "There are oil wells in Rainey which are a potential source of pollution, yet Audubon experience in the past few decades indicates that oil can be extracted without measurable damage to the marsh. Extra precautions to prevent pollution have proven effective."

Audubon officials involved with the project are more enthusiastic. John "Frosty" Anderson, the director of Audubon's Sanctuaries Department, is aware of environmentalists' charges that Audubon has been "bought off by big oil." "There's no denying that [Rainey mineral royalties] are significant in terms of revenue for Audubon," he says. But "The relationships we have had with oil companies over the years have been very satisfactory. As long as we know what precautions we want them to take, we have had no trouble in getting them to comply. We probably require them to take extra precautions simply because it is a wildlife sanctuary and we have a membership of over 400,000 who would be very irate if we polluted our own environment, our own land, our own sanctuary. The companies have leaned over backwards.

"After they've finished their drilling and they still have their equipment, if we need a job done with a drag line, they're usually happy to do it. So we have had some levees constructed and flumes installed so that we have water control that we could not have afforded if we would have had to pay for it." Consolidated Oil and Gas is one of three oil companies operating on the sanctuary. Lonnie Legé, speaking of their part in improving by tenfold the capacity of certain areas of the marsh to sustain wildlife, says, "They was real cooperative."

The Audubon Society oversees all activities in the sanctuary. An Audubon lawyer and geologist are involved with any development that could prove harmful to the marshland. O.R. Carter, the geologist employed to look out for Audubon interests, says, "I am very proud of the way industry has responded to Audubon's requirements. The Rainey preserve is the ideal way to manage lands in this country. To my way of thinking, the word is always conservation, in crucial minerals as well as the surface and wildlife. I don't know an area that minerals are being taken out of that is not of ecological concern.…The object is to manage it in such a way that maximum conservation is accomplished on all levels."

Speaking of government lands, Carter says, "There is undoubtedly a lot of land that the federal government has that could be returned to private hands, and there is no reason for the mineral resources to be tied up. We will all have to learn to replace and use things ultimately, but there's no reason that we should have to return to the dark ages to do it. [There is a] fantastic amount of acreage that the federal government owns, and the present laws are certainly a deterrent to developing desperately needed minerals on those acreages.…Returning government land to private property is the only way we can ever get the maximum utility from it. As a matter of fact, I think it's the only way to get the maximum utility of the ecology."

Such strong statements are not forthcoming from the public relations department of the Audubon Society. Frosty Anderson, the director of the Sanctuaries Department, is willing to admit, though, that government is probably the environmentalist's greatest enemy. And he finds it "ironic that the new administration has made a big issue of getting the government off our backs, but subsidized agriculture will probably be around for four more years at least, and it's ruining potentially productive land. We're paying to have our environment deteriorate."

Speaking of conservatives, Anderson says: "Some of the massive water management projects—real boondoggles, like the Garrison Diversion Project in North Dakota being built to irrigate roughly 250,000 acres—will by their own figures destroy 225,000 acres of already productive land that admittedly uses dry land farming. The great, strong promoter has been a hide-bound Republican, Senator Milton Young. It is ironic that conservative and conservation are not spelled with the same c."

The Rainey preserve was given to the Audubon Society by the estate of Paul J. Rainey in 1924. No drilling was done until the mid-'50s. There was no protest from members at the time, and the managers of the preserve simply went about the business of selling the drilling rights, though their present lawyer says that their lack of expertise at the time led them into some less-than-market-value deals. That has changed now, and Audubon is working out similar arrangements in other areas.

The Michigan Audubon Society plans to extract oil from a preserve there. In South Carolina, the society is attempting to maintain a hardwood forest area for a profit without the aid of potentially dangerous insecticides or destructive logging methods.

The drilling of an exploratory well at an Audubon preserve in Florida, however, has come under environmentalist attack. Though the platform will take up about one acre of nonsensitive land out of 11,000 acres in the preserve, Audubon is being heavily criticized for allowing the drilling, despite the fact that they only hold 25 percent of the mineral rights and could not stop the drilling if they tried.

Besides providing revenue for the ecological groups, enhancing their ability to acquire other lands, private ownership of lands enables them to use management techniques that would be illegal or impossible on government lands. The Rainey preserve, for example, uses controlled burning to encourage growth of the three-cornered grass that geese relish. Grazing is strictly controlled on the 8,000 acres of Rainey that are suitable for cattle. The herds not only represent another source of revenue but actually improve the environmental quality of the sanctuary by passing seed and breaking up the ground for plants that geese prefer. Frosty Anderson notes that on private preserves, "We are not forced to take the short-term attitude." Referring to biologists he knows who work for government preserves, he relates that "friends who insisted on enforcing grazing restriction for the long-run good of the land were somehow or another transferred to another refuge." He says government's Bureau of Land Management just doesn't have the clout to stand up to political pressures to use public lands, bringing on the familiar "tragedy of the commons."

The Nature Conservancy is another important group that buys and manages ecologically sensitive areas. A recent fundraiser emphasized: "We don't sue or picket or preach. We simply do our best to locate, scientifically, those spots on earth where something wild and rare and beautiful is thriving, or hanging on precariously. Then we buy them. We're good at it. In less than three decades we've acquired—by purchase, gift, easement and various horse trades—Rhode Island, twice over." The conservancy keeps about half the land it acquires, donating the other half to the government or local conservation groups. At least one of the reasons that they give land to the government is that the government doesn't often condemn its own land for some construction project or road.

One of the conservancy's most popular preserves is a bird refuge in Arizona, the Mile Hi/Ramsey Canyon Preserve. Cottages, pet-boarding facilities, and tours are available for a price. The project turns a profit and benefits other NC activities. Walt Matia, assistant director of stewardship, describes it as "a good, though atypical, example of making a preserve pay for itself." He adds that "certain lands can be managed with better results and at lower costs than can be done through a public agency," but he believes this is "probably the result of fewer regulations and public expectations and not any magic of free enterprise." Of course, the lack of regulations and exaggerated expectations are indeed part of the "magic of free enterprise."

Nature Conservancy turns down land every year from potential contributors because it does not fit in with their overall plans. But if the owners don't mind having the NC sell the donated land to buy other, more crucial, real estate, they will accept it. This conservationist group, at least, doesn't seem to mind a little horse-trading. It is that sort of rational behavior that is at the heart of our proposal.

The American political system is avowedly experimental. We here suggest an additional experiment. Assume that there is an area that may be developed for mining or that may be classified as wilderness. Under the current system, environmental interest groups may be expected to ignore the opportunity cost of wilderness classification and advocate this disposition of the land. Incremental units are added to the wilderness system, and the land is available for low-density recreation. In addition, the supply of valuable minerals is reduced, there is increased reliance on foreign sources for that mineral, and the price and uncertainty of its availability increase. Given the high degree of interdependence in the United States, nearly all citizens may be expected to pay this uncalculated opportunity cost. The self-interest of wilderness advocates imposes a cost on the rest of society. On the other hand, if miners prevail, they frequently destroy wilderness values, again without compensation to the rest of society.

What we propose is that lands presently included in the Wilderness System be put into the hands of qualified environmental groups such as the Sierra Club, the Audubon Society, and the Wilderness Society in exchange for (1) their agreement that in the future no wilderness areas be established by political fiat and (2) either their development of the acquired land (according to their own rules, of course, as in the Rainey case) or their clean-up of an environmentally degraded area be equal in size to the wilderness area acquired. The result would be that these areas, vast portions of which are currently closed to all mining activity, would be managed by groups with the expertise to weigh potential damage to the ecology against potential profits. (Existence as a membership organization might be a suitable criterion for qualifying as an environmental group.)

As a mental exercise, assume that an environmental interest group such as the Sierra Club is given fee title—full and transferable ownership—to wilderness land. This organization then has the opportunity to lease mineral rights and obtain the royalties. How would the organization behave? Assuming that the managers of the interest group are intelligent and dedicated individuals, they will attempt, in accord with their values, to maximize their potential value from the resource. Given that they have a general interest in wilderness values and that they are not totally oriented toward any specific land area, they will carefully evaluate the contribution that this land can make to their goals.

For example, if the area has a titanium deposit that is expected to yield $1 million worth of benefits, they would consider developing it. The basic questions they confront would include: (1) How much revenue will such an activity yield? (2) How much additional wilderness land may we buy with this income? (3) Is there a way to manage these lands that will permit mineral extraction while minimizing the impact on the wilderness features of the land?

Under these circumstances, as opposed to public ownership, the wilderness groups would be forced by self-interest to consider the opportunity cost of total nondevelopment. Further, rather than resolutely opposing the extraction of any commercially valuable resources from the land, they would focus on obtaining these resources while maintaining to the optimal degree the wilderness character of the area. Different incentives lead to different behavior.

Extraction of mineral or energy resources does not necessarily result in ecological wipeout, of course. Mining is not simply despoliation, although it can be. There are tremendous variations in the impact of alternative kinds of mining on an area, and the potential variation is much higher. (This is especially true for extraction of energy resources.)

Nor is it likely that many large mineral deposits would coincide with areas of critical environmental concern. Mining, by nature, has to be a very concentrated activity to pay. The total acreage mined for nonfuel minerals in the United States in the last 50 years is less than a million acres. According to Representative Santini's report to Congress, 90 percent of the free world's mineral requirements are supplied by less than 1,200 mines. So a small area of wilderness land in mineral production could make a tremendous difference in terms of America's mineral independence.

If an environmental group decided that the minerals in a particular area could not be extracted without greater damage to the land than the benefits of extraction, the group would simply be required to make improvements on an equivalent amount of land that had been damaged by previous activities of others now long gone. Conservationist groups could thus add to their stock while using their pool of voluntary labor to repair land that has not recovered from, say, primitive mining techniques.

One can conclude that rational managers of these groups would choose land that would enable them to do the most good in terms of their organization's goals. They could simply choose title to ecologically sensitive areas, but they would very likely consider the alternative uses to which the land might be put. Land that has a high economic value can be mined now or later, and it would be logical for the groups to opt for mineral-valuable land simply to ensure that it is developed according to ecologically sound standards. And they might choose to ignore ecologically crucial areas and go right for the most valuable mineral lands in order to raise the money to buy other sensitive areas. The end product—increased supply of minerals—is the same, and that end is accomplished in a way that moves the institutions of our society away from government solutions to a system of private property and choice.

This small change in the rules of the federal wilderness/minerals game could yield enormous social benefits. With land in private hands, all parties concerned become much more constructive in their thinking and language. Instead of discrediting the goals of others, the question becomes: How can our desires best be achieved at least cost to others? The owner thinks this way in order to capture more revenues, selling off the highest-valued package of rights consistent with his own goods. Similarly, a buyer of rights to mine, or a buyer of easements to conserve, wants to purchase his valued package at the least cost to the seller and thus to himself.

Also, the unlimited wants of every party are forced into priority classes. The most important land rights will be purchased; declarations that every contested acre is "priceless" become suitably absurd. Even people in single-minded pursuit of profits or of wilderness goals will act as if other social goals mattered. Indeed, they may seek out higher-valued uses of their own acreage, using profits to obtain new means to satisfy their own narrow goals. And after all, it is our actions, not the worthiness of our goals, that concerns the rest of society.

John Baden and Richard Stroup founded and direct the Center for Political Economy and Natural Resources at Montana State University. Baden is a political scientist; Stroup, an economist. Patrick Cox, their research associate for this article, has a B.A. in economics; he is a free-lance writer and REASON's Spotlight columnist.

This article is a project of the Reason Foundation Investigative Journalism Fund. Authors Baden and Stroup wish to express their appreciation to the Sarah Scaife Foundation for its support of research that contributed to this article.

HOW STRATEGIC ARE THEY?

Tantalum, antimony, iridium, palladium—they sound exotic, almost poetic. Yet they and a host of other minerals, some of them—asbestos and zinc, for example—more familiar on the tongue, are essential materials in a long list of ordinary products that contribute to our well-being: magnets, steel and stainless steel, automobile antipollution devices, jet engines, drill bits, surgical equipment, petrochemical refineries, glass-processing equipment, nontoxic paint, computer hardware, and so on and on. Such materials will also be vital to energy sources being developed in an attempt to reduce our dependence on imported oil: geothermal and ocean thermal energy, coal gasification and liquefaction, oil shale and tar sand development, fission and fusion.

For many of the essential minerals, however, the United States must rely in whole or in large part on foreign countries (see chart)—many of them unfriendly and volatile. Political disturbances in Zaire, for example, which harbors 65 percent of the non-Communist world's supply of cobalt—have precipitated manic-depressive changes in price over the last three years. The only domestic source of platinum-group metals is recycling; the rest is imported, mainly from the Soviet Union and South Africa.

Chromium, 91 percent imported, is used mostly in stainless steel, for its excellent properties of corrosion resistance and hardness at relatively low cost. "A chromium embargo by the USSR and Zimbabwe would bring the entire industrial world to its knees in just six months," says Rep. James Santini—as much because of its use in medical equipment as because of its use in automobiles.

The current worries about import dependence are put in perspective by William Dresher, dean of the College of Mines at the University of Arizona and a consultant to the National Science Foundation. In 1950, he points out, "this country depended on imports to meet half or more of its needs for only four of thirteen basic industrial raw materials.…In 1979, imports accounted for more than half of nine of these same thirteen mineral commodities." In those two decades, the United States moved from "a positive balance of trade in minerals to a deficit of more than $9 billion."