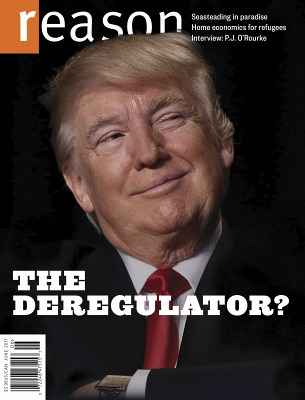

Trump's Deregulatory 'Juggernaut'?

Regulatory slowdown/rollback continues apace, but real deregulation requires congressional courage.

"While the Republican machine that emerged from the 2016 election may be sputtering on other fronts," The Wall Street Journal's Gerald F. Seib wrote this week, "it is proving to be a juggernaut on deregulation." But is that really true?

Seib notes that a recent U.S. Chamber of Commerce survey shows (in his phrasing) "29 executive actions…to reduce regulatory requirements," "100 additional directives that either knock down regulations or begin a process to eliminate or shrink them," "almost 50 pieces of legislation that have been introduced or begun moving through Congress," plus the overturning of 14 end-of-term Barack Obama regulations via the Congressional Review Act (CRA).

He does not mention, though you can read all about it right here, that the Competitive Enterprise Institute one month ago issued a report at the Trump administration's nine-month mark concluding that he is "the least regulatory president of all," with significant ($100 million and up) regulations down 58 percent from Obama's first 9 months of 2016, and significant proposed rules down 77 percent.

Those numbers are real, and meaningful. But "deregulatory"?

Slowing down and even blocking regulation is not the same as removing human activity from regulatory oversight by the state. It's true, the CRA (on which more below) has been used 14 more times under Trump than during all previous presidents combined, but that's against a backdrop of 2,183 rules issued during Trump's first nine months. In truth, there's really only so much that even the most deregulatory-minded president can do (and Trump has plenty of regulatory impulses as well). Real deregulation, as I spelled out in this magazine feature, must come from Congress:

"What deregulation meant [back in the 1970s] was we altered statutes," [Regulation Editor Peter Van Doren] explains. "Congress rewrote the laws." It's the underlying legislation, which instructs regulatory agencies to spend money and promulgate rules, that needs to be repealed, not just the odd stinkbud blooming at the end of the process. Even radical-sounding proposals, like the one-sentence bill introduced in February by the libertarian-leaning Rep. Thomas Massie (R–Ky.) to close down the Department of Education, ultimately "doesn't do anything," Van Doren argues. "You know why? The statutes!"

If you don't want federal money to be spent on education, he says, "you have to rewrite and/or eliminate the Elementary Secondary Education Act of 1965.…The Department of Education simply implements the ESEA, so if you eliminate the implementer, the law still exists." ("It's a fair charge," Massie acknowledges. "I had to decide whether to write a one-sentence bill that I could get a lot of people to agree with, or a very involved bill that talks about what happens to all that funding, and then people start disagreeing.")

So has this Congress, which has shown tangible enthusiasm both for killing stinkbuds and debating process-reform bills, started the hard work of repealing the problematic underlying laws? I'll answer the question with another question: Is the indefensible Jones Act still gratuitously hobbling hurricane-ravaged Puerto Rico?

As Susan Dudley, the regulatory studies director at George Washington University and former administrator for the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, recently concluded, "Despite some promising bipartisan efforts, the 115th congress has failed to make much progress on regulatory reform legislation, and the opportunities for doing so are rapidly diminishing."

However, Dudley also reports on an interesting new CRA wrinkle that could swell the list of potentially reviewable regulations into the thousands:

The window for such disapprovals was widely thought to have closed in May, but just last week, congress showed that it is not ready to mothball the Congressional Review Act (CRA) yet. It disapproved a recent Consumer Financial Protection Bureau rule and sent it to the president's desk. Perhaps an even more significant sign that the CRA is still viable is a new Government Accountability Office (GAO) letter confirming that the law gives congress the ability to veto agency guidance documents….

The less-reported bit of news on this front came in the form of a letter from the GAO to Senator Pat Toomey (R-PA). Toomey asked whether a guidance on leveraged lending issued jointly more than four years ago by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, was a "rule" for purposes of the CRA. The GAO responded on October 19 that it was.

As an earlier column (CRAzy After All These Years) observes, this opinion could put hundreds or even thousands of rules within the scope of congress's disapproval powers. This is because congress's 60 legislative-day review clock doesn't start ticking until a rule is published or until the issuing agency submits a report to the GAO, whichever comes later. As a former Congressional Research Service analyst documented, agencies neglected to submit reports to GAO for hundreds of rules since the CRA's passage in 1996. The broad definition of rule the GAO confirmed in the Toomey letter expands those numbers to thousands.

Perhaps even more interesting, according to the Wall Street Journal, "the Senate parliamentarian has found that the GAO ruling counts as the official report," triggering the review clock for the interagency leveraged lending guidance.