Report: 38 Percent of FEMA Employees Aren't 'Qualified' for Their Jobs

At the height of the agency's deployments in the summer of 2017, 54 percent of staff were serving in a capacity for which they were not fully qualified.

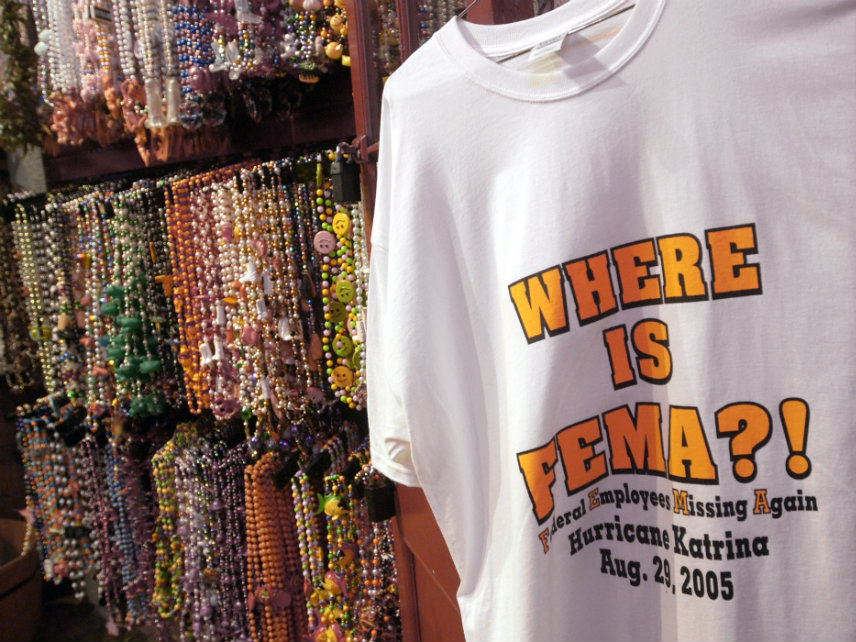

If it sometimes seems like the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) doesn't know what it is doing, well, that might be because many FEMA employees don't know what they are doing.

As part of an ongoing review of its response to the 2017 hurricane season—a particularly bad summer that included major storms hitting Florida, Puerto Rico, and Texas—FEMA concluded that as many as 38 percent of it's workforce were unqualified for the positions they held, according to Politico. Being unqualified, in this case, means those employees had not completed mandatory training for their current position.

As a result, FEMA "placed staff in positions beyond their experiences and, in some instance, beyond their capabilities," according to the agency's internal analysis of the 2017 hurricane season.

The number of FEMA employees who are qualified for their jobs has actually ticked up since 2017. At the height of the agency's deployments in response to that summer's storms, 54 percent of staff were serving in a capacity for which they were not fully qualified, according to a September 2018 report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

"FEMA officials noted that staff shortages, and lack of trained personnel with program expertise led to complications in its response efforts, particularly after Hurricane Maria," the GAO found.

While FEMA distributed more than 35 million meals in Puerto Rico after Maria made landfall, the agency's response was widely criticized for taking longer than it should have—the agency has admitted it failed to prepare adequately for the storm—and for logistical failures like leaving nearly 1 million bottles of water at an airstrip that were apparently never distributed to stricken Puerto Ricans. The storm may have killed as many as 3,000 people, though tallying the human cost has had its own problems.

It might seem like one solution to FEMA's staffing problem is to commit more funding to the agency for hiring and training. But from top to bottom, FEMA has proven itself to be a poor steward of tax dollars. Just three months ago, FEMA Administrator Brock Long was criticized by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Inspector General for having blown $150,000 on personal travel expenses. Among other things, Long had hired a chauffeur to drive him from Washington, D.C., to his home in North Carolina for weekends. On at least one occasion, an aide picked up Long's children from their school, as Reason's Zuri Davis reported in September.

Others at FEMA are no better at managing the public's money. A December 2017 report by the DHS inspector general found that FEMA's "lack of process" for tracking insurance reimbursements leaves "billions of taxpayer funds" possibly wasted. In 2015, for example, FEMA spent more than $450 million—about 30 percent of its total disaster relief expenditures for the year—on "questionable costs," including "duplicate payments, unsupported costs, improper contract costs, and unauthorized expenditures," according to the DHS Office of Inspector General.

With that sort of track record, there's no reason to continue throwing money at FEMA. Instead, the lack of "qualified" employees is an opportunity to reassess exactly what FEMA is capable of doing competently with the money it has.

The federal government is probably going to continue to play some role in the aftermath of major natural disasters, but FEMA is never going to be able to react to changing on-the-ground circumstances as quickly or effectively as private operators with established ties to the effected communities and supply chains that are already in place. Think Waffle House. Or Walmart.

Perhaps FEMA should stop trying. A narrower focus could let FEMA do more with less, allowing the agency to train a smaller number of employees to handle high-level emergency response roles and keep better track of relief dollars. Offloading duties that are better handled by local or state governments and private businesses would improve FEMA's effectiveness—and, more importantly, disaster relief operations for those who need them most.