Grieving Parents' Policy Preferences Are Irrelevant to the Constitutionality of Gun Laws

Kamala Harris wants Brett Kavanaugh to give gun violence victims "a fair shake," by which she means adopting her view of the Second Amendment.

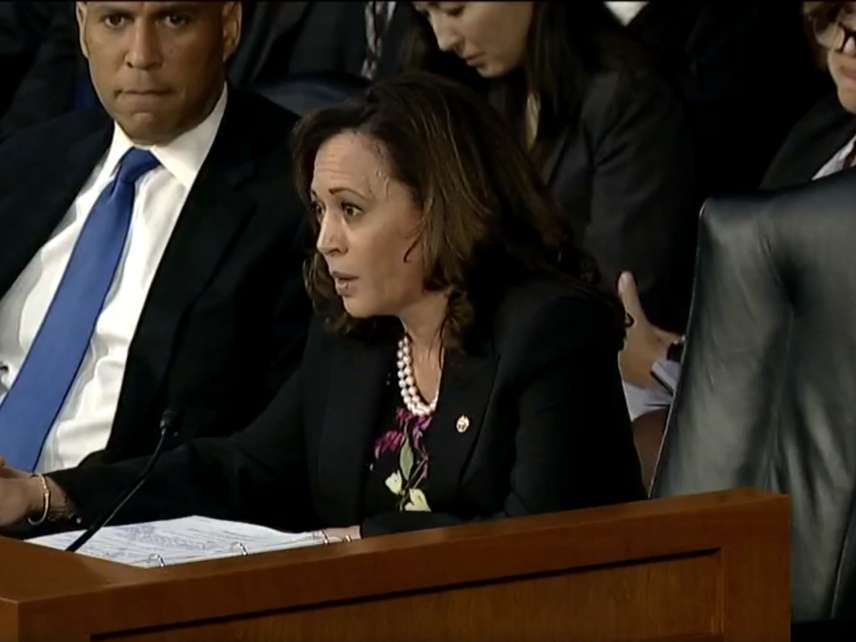

Whether or not Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh deliberately spurned a handshake with the father of a teenager who died in the Parkland massacre, the response from Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) was puzzling. "If Kavanaugh won't even give him a handshake," she tweeted, "how can we believe he would give gun violence victims a fair shake in court?"

Unless Harris imagines that one of the doomed lawsuits charging gun makers with complicity in mass shootings will somehow make it to the Supreme Court, she presumably had in mind the next time the justices decide to hear a Second Amendment case. But "gun violence victims" are not parties to such cases, which involve individuals who challenge the constitutionality of legal restrictions on firearms. Harris' misrepresentation of what's at stake in that situation reflects a broader strategy of replacing logic with emotion in the campaign for stricter gun control.

A father's grief is not an argument for the effectiveness of any particular gun control law, and it certainly is not an argument for the constitutionality of that law. Contrary to Harris' implication, it is not relevant in deciding whether, say, a ban on so-called assault weapons is consistent with the Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms.

"We have witnessed horrific mass shootings from Parkland to Las Vegas to Jacksonville, Florida," Harris said in her opening statement during Kavanaugh's confirmation hearing yesterday. "Yet Judge Kavanaugh has gone further than the Supreme Court and has written that because assault weapons are in 'common use,' assault weapons and high-capacity magazines cannot be banned under the Second Amendment."

Kavanaugh's argument in the 2011 case to which Harris referred, where he dissented from a D.C. Circuit decision upholding a local ban on certain arbitrarily selected semi-automatic rifles, was a pretty straightforward extension of the Supreme Court's logic in the landmark 2008 case District of Columbia v. Heller. "In Heller," Kavanaugh noted, "the Supreme Court held that handguns—the vast majority of which today are semi-automatic—are constitutionally protected because they have not traditionally been banned and are in common use by law-abiding citizens. There is no meaningful or persuasive constitutional distinction between semi-automatic handguns and semi-automatic rifles. Semi-automatic rifles, like semi-automatic handguns, have not traditionally been banned and are in common use by law-abiding citizens for self-defense in the home, hunting, and other lawful uses. Moreover, semi-automatic handguns are used in connection with violent crimes far more than semi-automatic rifles are. It follows from Heller's protection of semi-automatic handguns that semi-automatic rifles are also constitutionally protected and that D.C.'s ban on them is unconstitutional."

Maybe Kavanaugh misapplied Heller. Maybe Heller misinterpreted the Second Amendment. Maybe Harris believes both of those things. But the fact that "horrific mass shootings" occur, or that they leave behind grieving parents, has nothing to do with those questions. If Kavanaugh is on the Supreme Court when it hears a challenge to an "assault weapon" ban, he will owe a "fair shake" to the people claiming the law violates their constitutional rights and to the government lawyers claiming it does not. The policy preferences of gun violence victims, no matter how heartfelt, should not carry any weight.