Scooter Libby Aside, Presidential Pardons Are Good and Trump Should Issue Even More of Them

"I don't know Mr. Libby, but for years I have heard that he has been treated unfairly."

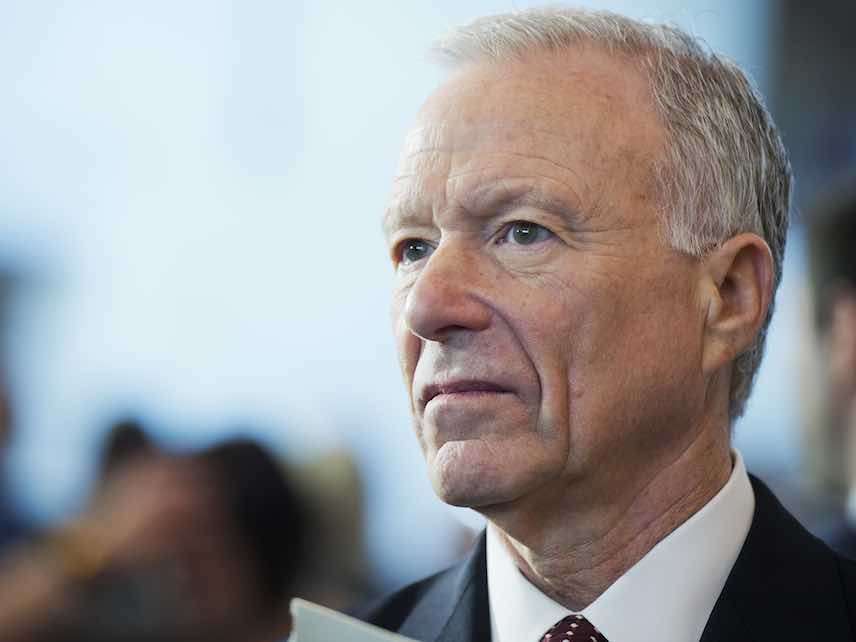

President Donald Trump announced today that he is pardoning Lewis "Scooter" Libby, a vice presidential aide convicted in 2005 of obstructing justice. Thanks to a commutation from then-President George W. Bush, Libby served no time, though friends of Libby had always hoped to win him a full pardon.

Trump has now delivered just that. Given the timing, and given the familiar details of the Libby case, Trump's reason for doing so seems obvious: He wanted to send a very clear message that he is perfectly willing to pardon government officials who stay loyal to the president in the face of Bob Mueller's investigation.

That's wrong. But issuing pardons, as a general matter, is not. In fact, Trump should issue even more of them.

I say that even though the Libby pardon look like a craven political move. Libby was charged with lying to officials investigating an incident in which a CIA officer's covert status was leaked to the media. The officer, Valerie Plame, believed members of the Bush administration had orchestrated the leak to punish her husband, Joseph Wilson, a vocal critic of the Iraq War. Investigators never proved a definitive connection, but they did build an obstruction case against Libby. Many believe that Libby took a fall to protect his boss, Vice President Dick Cheney. (The special prosecutor in that case, Patrick Fitzgerald, was appointed by then Deputy Attorney General James Comey.)

"I don't know Mr. Libby, but for years I have heard that he has been treated unfairly," said Trump in a statement. "Hopefully, this full pardon will help rectify a very sad portion of his life."

Trump has also made clear that he thinks Mueller's investigation into his campaign's possible collusion with Russia is unfair. Pardoning Libby certainly seems like one way for Trump to discreetly assure any supporters touched by the Mueller investigation that he will take care of them in the long run—if they cover for the president.

It's possible to be both underwhelmed by the Russia probe and worried about Trump's efforts to thwart it. An overzealous state intelligence apparatus is a threat to the rule of law, and so is a president who does anything he can to keep himself and his cronies out of jail.

But all that aside, it would be a terrible shame if Trump's decision to pardon Libby had the effect of tainting pardons in the public's eye. Pardons and commutations are a good and useful tool to free people who don't belong in prison. President Barack Obama, for instance, commuted the sentences of 330 federal inmates, many of whom had received incredibly harsh sentences for minor drug violations. He also commuted the sentence of former U.S. Army analyst Chelsea Manning, who had been convicted of disclosing classified materials. Manning had indeed broken the law, but she had done so in order to expose a greater evil—wrongdoing by the U.S. government. Short of a full pardon, commutation of Manning's sentence was the best way to handle the situation.

Instead of pardoning obnoxious and objectively evil political supports like Sheriff Joe Arpaio, Trump should consider pardons and commutations for nonviolent drug offenders, whistleblowers like Edward Snowden, and Silk Road founder Ross Ulbricht, whose life sentence was vastly disproportionate to his crimes.