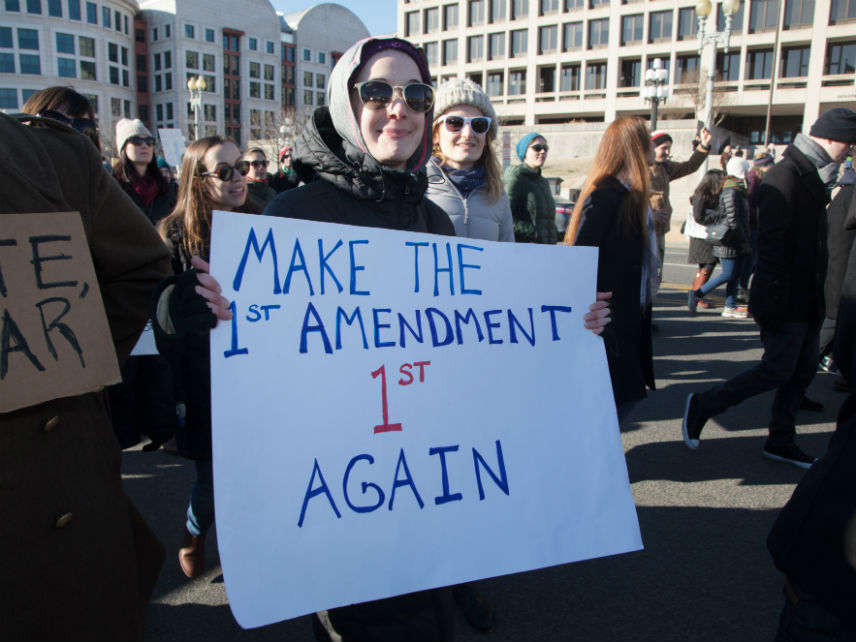

ACLU Sues D.C. Metro for Rejecting Ads, Including One With Text of the First Amendment

A dumb government rule to protect subway riders from controversial ads gets predictable results.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is suing the D.C.'s dysfunctional and much-loathed transit authority for rejecting subway ads the government deemed too controversial, including one that contained the text of the First Amendment.

The ACLU announced Wednesday that it was filing suit against the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) on behalf of four plaintiffs, including itself, who were denied advertising space by the government agency. The other plaintiffs are People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), a local abortion provider, and noted troll Milo Yiannopoulos. (Something for everyone to hate!)

All of the groups had ads rejected by Metro for running afoul of its policy against advertisements that are "issues-oriented" or "intended to influence members of the public regarding an issue on which there are varying opinions." Metro rejected several ACLU ads in 2016 and 2017, for example, that displayed the text of the First Amendment in several languages. In Yiannopoulos' case, Metro placed ads for his recent simulacrum of book, but took them down after it received complaints.

The ACLU argues the rules are unconstitutionally vague and restrictive, violating the First Amendment.

"The four plaintiffs in this case perfectly illustrate the indivisibility of the First Amendment," Lee Rowland, a senior staff attorney with the ACLU, said in a statement. "In its zeal to avoid hosting offensive and hateful speech, the government has eliminated speech that makes us think, including the text of the First Amendment itself. The ACLU could not more strongly disagree with the values that Milo Yiannopoulos espouses, but we can't allow the government to pick and choose which viewpoints are acceptable."

Metro adopted those guidelines after anti-Islam activist Pamela Geller attempted to purchase ads on Metro in 2015 that showed a cartoon of the prophet Mohammed.

The new rules' results were entirely predictable: Metro employees, tasked with determining what is too controversial for the mores of morning commuters, restricted speech based on undefinable terms and inconsistent guidelines. They err on the side of censorship because their jobs depend on it, and because there's always someone somewhere waiting to be offended.

Note that Metro does not consider the ubiquitous ads for Pentagon contractors such as Northrop Grumman and Raytheon to be "issue-oriented," even though they are clearly placed to influence legislators and bureaucrats, because those ads have a profit motive at heart. Apparently the text of the First Amendment is a policy issue on which sides disagree, but an ad for a taxpayer-funded F-35 at the Pentagon Metro stop is just a marketing opportunity.

The ACLU's lawsuit is a laudable continuation of the sort of work that defined the organization: fighting for free speech in cases that others lack either the principles or the stomach to stand up for.

It's all the more important because there is increasing pressure to abandon free speech as an unfettered good—and the pressure isn't just coming from the outside. One ACLU lawyer, Chase Strangio, released a personal statement on Twitter yesterday explaining why he thinks the ACLU was wrong to defend Yiannopoulos' First Amendment rights. His statement included a curious sentence: "Though his ability to speak is protected by the First Amendment, I don't believe in protecting principle for the sake of principle in all cases."

That's a confused way of saying he's unprincipled, since the entire point of principles is they don't change according to circumstance.

Fortunately, there is still enough principle left at the ACLU to fight for controversial speech and against dumb government rules.