Capitalism in the Cracks: How Japan's Microspaces Unleash Economic Experimentation

These spaces are so small that most cities would ignore them. Tokyo doesn't.

This is part of Reason's 2025 summer travel issue. Click here to read the rest of the issue.

A three-story house tucked into a mere one-meter gap between tall buildings. A flower shop shaped like a triangle, wedged between a retaining wall and the sidewalk. A standing bar humming with laughter beneath the rumble of passing trains. In most cities, these spaces would be dead zones—awkward, overlooked, written off by zoning and building codes as unusable.

But in Tokyo, they bloom with life. These microspaces are amenities. They're capitalism in the cracks, not just in form but in function.

These strange slivers often become homes for new ideas: a two-person bar, a bookstore barely wider than a fridge, a late-night shop that opens on a whim. They invite experimentation, economic as well as architectural.

Tokyo's ability to cultivate these spaces isn't just a cultural quirk. It's a byproduct of a city that leaves room for improvisation, that adapts to its imperfections, and that transforms constraints into creativity. These spaces reveal what is possible when cities loosen their grip on regulations—when policy becomes an enabler, not a gatekeeper. They offer a glimpse of what urban life could look like if more places embraced flexibility.

Tokyo's urbanism emerged more than it was planned. Most of its neighborhoods weren't drafted in a planner's office. They were shaped incrementally by individuals responding to need and opportunity.

Modern Tokyo is a city born from ruin. After the devastating bombings of World War II, with little funding available for formal reconstruction, residents rebuilt on their own—using salvaged materials to create homes on the ruins of old neighborhoods. Over time, the government stepped in to connect and formalize what had already taken shape. The result is a dense, oddly beautiful patchwork: irregular lots, winding streets, and spaces so small that most cities would ignore them. But Tokyo doesn't.

There are at least three varieties of microspaces here: pet architecture, yokochos, and undertrack infills.

***

Of all of Tokyo's urban quirks, few are as endearing—or revealing—as pet architecture.

Coined by the architectural firm Atelier Bow-Wow, the term describes buildings that are "unusually small, humorous, and charming": little pets in a city built for human beings. Awkwardly shaped and impossibly tiny, they defy conventional notions about how much space is necessary for any given use.

You might stumble upon a rubber stamp store crammed into a leftover triangle of land between a train line and the road in Nakano. A one-meter-wide real estate office in Shimokitazawa. A tiny bakery that somehow fits between a wall and a utility pole in Koenji. These are buildings that shouldn't exist, but they do.

In many cities, spaces like these would be rejected outright as unusable. They'd run into a wall of regulatory barriers: minimum lot sizes, minimum unit sizes, parking mandates, and zoning codes that separate uses into rigid slots—residential here, commercial there, industrial somewhere else.

But in Tokyo, they're opportunities. They challenge bureaucratic assumptions about what buildings are supposed to look like. As the Atelier Bow-Wow architect Yoshiharu Tsukamoto has put it: "They illustrate unique ideas with elements of fun, without yielding to unfavorable conditions." Pet architecture is playful, it's resourceful, and it's all over the city.

***

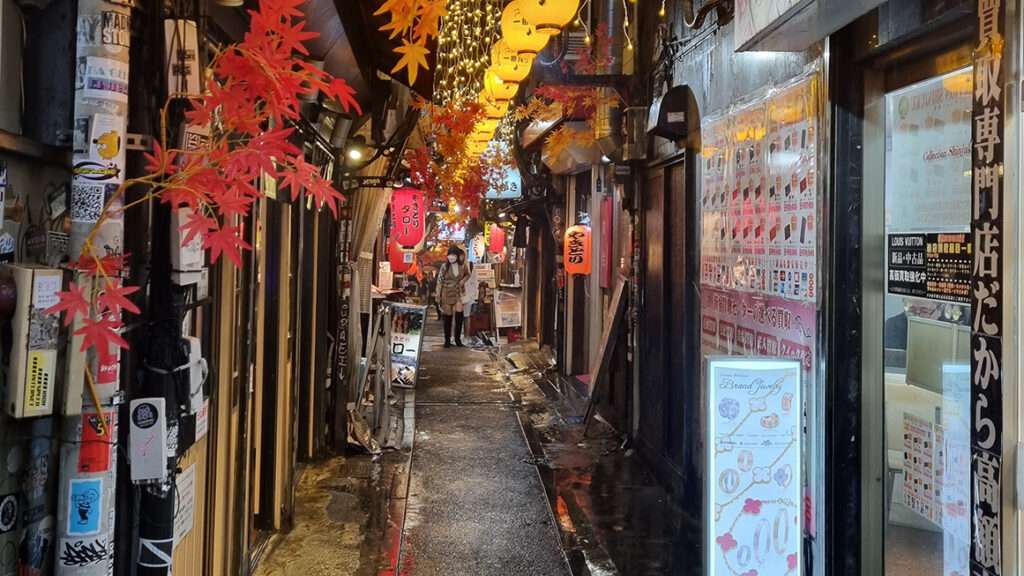

Yokocho literally means "side street" or "alleyway." In Japan, it means something more: narrow lanes filled with tiny bars and restaurants. Usually found near train stations or commercial centers, these narrow streets range from just 1.3 to 2.8 meters wide—narrow enough to stretch out your arms and touch both walls, too tight to meet code in most U.S. cities. Inside, you'll find bars the size of walk-in closets, seating six to 12 patrons and often run by a single staffer.

Yokochos emerged after World War II as black markets. They were improvised stalls selling basic goods. Over time these stalls became food joints and drinking dens, and eventually they were fixtures of Tokyo's urban landscape.

The Golden Gai district in Shinjuku packs more than 200 tiny bars into six alleyways in an area smaller than a city block. (It's the kind of setup a North American fire marshal would never allow.) Most buildings are two stories high, with steep staircases leading to completely different experiences upstairs. Want a fancy whiskey bar? It's there. A horror movie–themed bar? Absolutely. Hospital-themed? Erotic fetish? Retro video games? A quiet library bar? They have all of the above. All unique. All impossibly small.

Nearby, on the other side of Shinjuku station, the Omoide Yokocho district is known for late-night yakitori (chicken skewers) and drinks, with around 80 shops squeezed into a single alleyway. In Shibuya, Nonbei Yokocho—or "Drunkard's Alley"—crams 40 shops into spaces barely two meters wide. And in Ebisu, Ebisu Yokocho sits in a covered passageway built on the remnants of a former shopping center that houses izakayas (Japanese pubs) ranging from 10 to 16.5 square meters, serving everything from grilled fish to okonomiyaki to oden.

So beloved are these places that developers have recreated them inside modern buildings. Shibuya Yokocho, a sleek version inside the Miyashita Park complex, mimics the feel of the real thing, with curated chaos, shared tables, and dishes from every prefecture in Japan.

Nostalgia aside, yokochos are more than relics. Their size, affordability, and independence make them incubators for creativity and entrepreneurship.

***

Tokyo's rail system is everywhere—and wherever there are train tracks, there are gaps. In many cities, these would be fenced off. In Tokyo, they're filled with life.

Like yokochos, many undertrack infills began as black markets after the war. What were once dusty, makeshift stalls have since evolved into hubs of commerce and dining.

Near Ueno Station, izakayas nestle underneath and between train lines. You can sit shoulder-to-shoulder with salarymen, sip a highball, nibble on sashimi, and watch the trains pass overhead.

A few blocks from there is Ameyoko, a market wedged beneath the Yamanote Line between the Okachimachi and Ueno stations. It's a sensory overload: cosmetics, spices, fresh seafood, and cheap street snacks packed into a narrow pulsing corridor under the tracks.

A few stops away on the Yamanote Line, in Yurakucho, rows of cozy restaurants and standing bars are tucked into the arches beneath the tracks. Some are linked by narrow alleyways that run under the railway itself, connecting one lively pocket to another. At around 6 p.m., the lights come on, the smoke rises, and the area fills with after-work revelers grabbing food and drinks before catching their train home.

What unites these undertrack infills is their uncanny ability to turn infrastructure into opportunity. Instead of ignoring the voids created by transit, Tokyo builds into them.

***

To understand why Tokyo looks the way it does, you have to start with zoning. Zoning laws determine what can be built and where—homes, shops, factories, or nothing at all.

In the U.S., zoning is local. Each city or county writes its own code, but most follow similar templates. Neighborhoods are typically residential, commercial, or industrial, with little room for overlap. The rules are rigid. It's often illegal to run a small business out of your home or to build on a lot deemed too small. Any change of use typically requires hearings, permits, consultants, and months—maybe years—of paperwork. It's a large bureaucratic system that tends to push out small, experimental, or unconventional uses.

Japan takes a different approach. The same zoning system applies nationwide, from Tokyo's densest neighborhoods to the smallest rural town. The rules are meant to maintain the scale of buildings, preserve sunlight access, and prevent fire hazards.

Instead of rigid land-use rules, Japan uses a set of 12 flexible zoning categories, arranged on a spectrum from residential to commercial to industrial. These are broad guidelines, not strict prescriptions. Within them, landowners are largely free to decide how to use their space.

Take Category 1, officially designated as "exclusively residential." In practice, that doesn't mean only homes can be built. Small shops, dental clinics, hair salons, and day cares are all permitted. What's prohibited are large, disruptive developments. You won't find a department store in Category 1, but you might find a ramen shop on the ground floor of someone's home.

Each zone builds on the one before it. If something is allowed in Category 1, it's automatically allowed in Categories 2 through 12. The only major exception is strictly industrial areas. Elsewhere, layers of possibilities build on each other, allowing for the kind of vibrant, fine-grained mixing of activities you see in Tokyo.

Japan also avoids rules that would make small-scale development impossible. There are no minimum lot sizes. Small parcels can be freely subdivided. Building heights are based on road width, not a fixed number. And it's legal to run a business out of your house. The result is a city that allows for increasingly complex and nuanced configurations.

The rules are more like scaffolding than a straitjacket. They set the frame, but decisions are left to property owners, architects, and builders.

This flexibility has made Tokyo radically adaptable. It makes space not just for small businesses but even smaller microbusinesses. If you have an idea and a few square feet, you can start something without hearings or expensive consultants.

"There are a lot of ways in which not only zoning but other pieces of the puzzle all come together to encourage these experimental, intimate, small-scale mom-and-pop businesses," explains Joe McReynolds, an urban studies scholar at Keio University's Almazán Architecture and Urban Studies Laboratory. "There's a lot of tilt in the regulations toward small businesses," he says, from lower taxes and simpler food safety rules to the relative ease of getting a liquor license.

Tokyo may be unique, but you can sometimes spot a glimmer of flexibility even in cities with heavy-handed planning systems.

Take London. With its heritage protections, conservation zones, strict building codes, and endless red tape, changing the built environment there often means running an obstacle course of applications, consultations, and design reviews. Yet small-scale invention sometimes slips through.

In West London's Bayswater conservation area, where uniform facades and historical preservation rules are the norm, you'll find the Gap House. With a street frontage of only 2.3 meters (8 feet), this five-story home fills what was once a narrow alley between two buildings.

"My inspiration was Japan and the Netherlands," explains the architect (and owner), Luke Tozer. "Both make good use of small bits of land."

The project required extensive negotiation, creative diplomacy, and imaginative design work to bring neighbors and planners on board. "We ultimately convinced them of a design that could be contemporary and sympathetic to the adjoining areas without it trying to mimic them," Tozer says. "One of our arguments was [that] it should be different because it's obviously of its time but also we want to try and still make it clear that it is a gap."

The result is a home that opens into a rear garden and maximizes every inch of its narrow footprint. "It required some imagination. Thinking out of the box. Good design, that's where it comes in," Tozer reflects. "That's where good design adds value on tricky sites."

The Gap House shows that even in cities bound by strict zoning and preservation overlays, there's still room for architectural courage.

"I love the fact that in a city—even a city where you've got an acute housing crisis like in London—there are always bits of land that are left over, forgotten," Tozer says.

There are cracks worth filling. But if every project demands a fight, we will never see this kind of development flourishing.

"Letting people run a little coffee shop, a little bookstore out of the ground floor of their houses, that's the sort of thing that makes a neighborhood charming and local and lovable and livable," McReynolds says.

That's part of what makes Tokyo so magnetic. It's a city where the unexpected flourishes. Walk a single block and you'll see a narrow home tucked between buildings, a pet-sized owl café, or a triangle-shaped standing bar. It's this patchwork—this mixture of building scales and uses—that gives the city its pulse.

Tokyo can't be copied. Its history is unique. But we can learn from its ethos of trusting its citizens and adopting policies that enable rather than restrict. If more cities embraced the idea that flexibility breeds vitality, we might start to see cracks of our own—cracks that could be filled with opportunities.