Tiny Nations in the Crack of the Map

You could travel to a foreign country, or you could create your own.

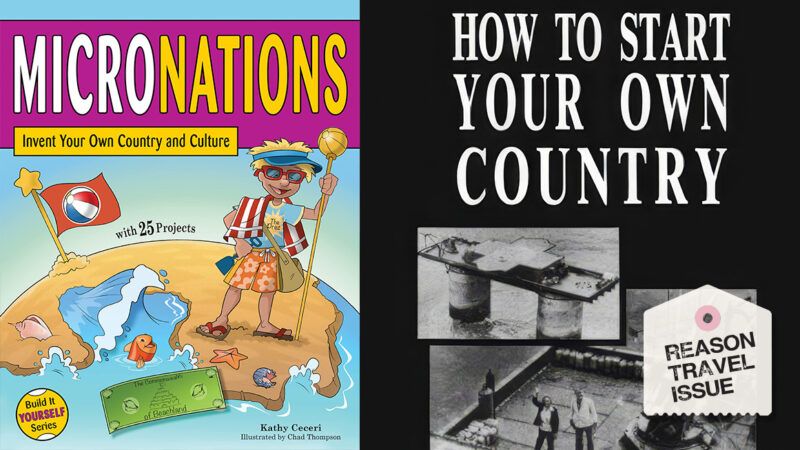

Micronations: Invent Your Own Country and Culture with 25 Projects, by Kathy Ceceri, illustrated by Chad Thompson, Nomad Press, 128 pages, $16.95

How To Start Your Own Country, by Erwin Strauss, Paladin Press, 170 pages, $20–$50 used

After the initial thrill of a few stamps on one's passport, the idea of touching down in yet another nation-state may seem jejune. After you've seen one nation-state, how truly different can another one be? Airports and highways with instantly navigable signage, cultures and cuisines flattened to meet the supply and demand of global trade, traditions reduced to photo opportunities—just more of the same.

The English essayist Samuel Johnson wrote that "the use of travelling is to regulate imagination by reality, and instead of thinking how things may be, to see them as they are." More and more, it seems that "how things are" doesn't require much travel at all to understand, and that despite the endless stream of novelties that bombard us, our imaginations are regulated by the ruthless bottlenecks of our streamlined and optimized modern world. Can we still imagine a place where we truly make our own decisions, where we own the glory and duty borne of each victory and each defeat? Can we imagine a place where every person stands without privilege or prejudice under our shared sun?

If we cannot visit this utopia, and if we cannot wave a wand and bring the whole system down tomorrow, then perhaps we can do something else: carve out a place where our wishes and our dreams override the unending bustle of the crowded world. Perhaps as a stepping stone to a world without kings, we can stand up and declare ourselves the equal of any empire or republic. We can raise our own flags and deflate the self-importance of the state's pageantry. We can travel to a place where, contra Johnson, our imagination regulates reality. We can become nations ourselves.

Over the last few decades, a number of hobbyists and eccentrics have done just this, declaring the independence of their apartment, their backyard, or, in one notable case, a raft anchored by a Ford engine block off the coast of Jamaica. A few of these independent-minded pranksters have graduated to become bona fide nuisances to the world of nation-states, but the vast majority don't take themselves or their self-declared sovereign power very seriously. These kings and presidents-for-life have become part of a community of "micronations."

In her 2014 book Micronations: Invent Your Own Country and Culture with 25 Projects, Kathy Ceceri laid out a series of activities designed to walk children through the steps of declaring independence, from writing a constitution to designing a sweet sash. The book includes brief interviews with figures who will be familiar to anyone who has studied the world of micronations, including Kevin Baugh, the longserving president of Molossia (located in Nevada, or surrounded by Nevada, depending on how you look at it), and His Imperial Majesty Doctor Eric Lis of the Aerican Empire (located in cyberspace and allegedly in outer space, though Lis himself lives in Canada).

Ceceri doesn't just stick to the fun stuff, like using stickers to make your currency harder to counterfeit. She also uses this whirlwind tour of national symbology and identity to create a primer that walks children through the basics of culture, economics, law, and international relations. If you've got a middle schooler in need of a rainy-day project, then Ceceri has created a cheerful and informative book that will provide them with a lot of fun while sneaking in a bit of learning.

All of those activities are literally child's play next to the DIY projects mapped out in Erwin Strauss' cult classic How To Start Your Own Country. Strauss, a passionately libertarian figure in science-fiction fandom, first published this slim book in 1979 and expanded it for a second edition in 1984. At first it feels almost entirely tongue-in-cheek. But when Strauss lays out the approaches an aspiring nation-state might use to gain independence, he starts with the observation that a nation has to have territory and hold it. This leads him into a multipage discussion of topics ranging from accepting the economic domination of larger powers to whether a libertarian enclave can ethically threaten the use of weapons of mass destruction to maintain its independence—heady stuff for page 22 of any book.

If nuclear brinksmanship isn't how you'd like to spend your free time, Strauss walks through some other paths to independence or quasi-independence: setting up shop under a "flag of convenience," a legal battle, simply disappearing off the grid, or setting up a model country (what we would now call a micronation). Strauss puts less effort into giving readers the tools they'll need to organize a successful nation and recruit a population, topics that likely merit books of their own.

All of this makes up a mere third of the book. The remainder is dedicated to a series of small articles detailing different micronations, seasteads, and other secessionist projects of varying seriousness. For younger readers, this might come across as a cop-out, but for readers who grew up in the pre-Wikipedia age, this was the true delight of the book. It was a steady, driving, seemingly endless march of stories that appeared in no history we'd heard of, from Outer Baldonia, a North American "principality" that no one involved took seriously, to the Floating Republic, a brief 1797 alliance of British mutineers that made the very serious demand that London stop fighting Napoleon. After a few pages, it began to shake your faith in yourself. "How did I not know this?" "Can you really just do that?" "Why didn't that revolt succeed?" You might breeze past a handful as curiosities. Assembled in ranks of dozens, that list of enclaves and ministates and freeholds began to seem more like forbidden knowledge.

Today, we live in a world of listicles and clickbait trivia, and any random teenager can look into their phone and fire off the facts they just learned to an audience of millions with the easy authority of a tenured professor. Strauss' volume lived in that same space, years before most of us set aside the authority of academia or the library's reference section for the immediate satisfaction of the top three search results. How To Start Your Own Country presented an alternate world, and finding it in a used bookstore or a head shop could seem like finding Narnia in a wardrobe.

***

The book sits at the center of today's micronationalism movement, which has exploded in size and popularity as the internet has lowered the barriers to entry. Wikipedia details dozens of micronations, and hundreds more can be found elsewhere on the internet. By gathering the stories of early micronations, Strauss jumpstarted this community.

He inspired more than just hobbyists. Venture capitalist Peter Thiel is just the most visible of the many figures who dream of establishing truly sovereign micronations on artificial "seasteads," and in 2009 Strauss spoke at a conference held by the Thiel-funded Seasteading Institute. Strauss' offhand suggestion that aspiring heads of state might begin by co-opting a friendly nation as a "flag of convenience" is visible across the world. As our world becomes ever more interconnected and instantly legible, we have ironically learned more and more that the clean lines on our maps mean less than the flow of money and influence. In the course of suggesting that anyone could run a country, Strauss made his readers think about what people who run countries actually do. For some readers, this was an inspiration; for others, a warning.

Strauss' text is no longer in print, but copies are readily available. While it may be dated in many regards, it still provides the reader with a perspective and a sense of possibility that few books do. You could travel to a foreign country, or you could start seeing the patch of the world where you stand in new and exciting ways. And if you decide to turn that bit of land into a foreign country, well, Strauss has you covered.