Why We Don't Worry About Scarlet Fever Anymore

The infection killed millions of people throughout history. Today it's considered a mild illness.

My 1-year-old daughter recently got sick. She cried nonstop, she ran a fever, and her body broke out in a fiery red, spotty, measleslike rash. But it wasn't measles. (Recent outbreaks notwithstanding, that disease is blessedly rare in the U.S., thanks to widespread vaccination.)

Alarmed by the spreading rash and worsening symptoms, I rushed my screaming toddler to an emergency room, where a doctor calmly diagnosed her with scarlet fever.

I thought I had misheard. Scarlet fever sounds like something from a different century.

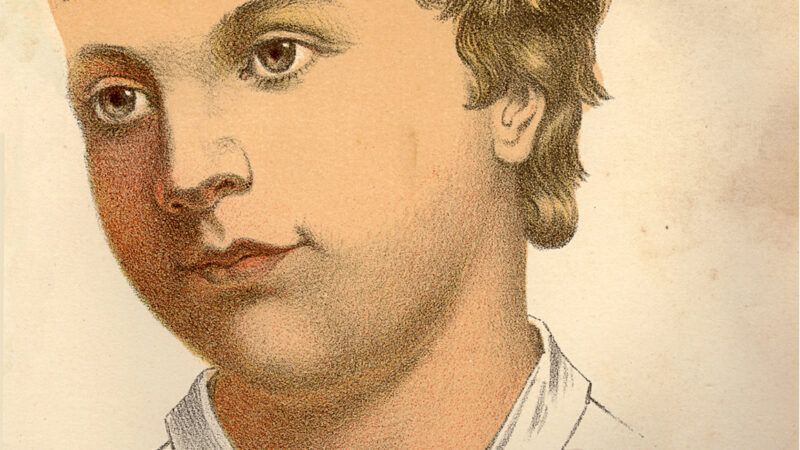

Many people today are only vaguely familiar with the term from classic literature. Scarlet fever is prominently featured in the plots of many old books, such as Frankenstein, Little Women, The Velveteen Rabbit, and Little House on the Prairie. The disease is described in Anna Karenina as an inevitable part of life. Scarlet fever's prominence in fiction makes sense, given that many writers once had real-life experience with the illness. Little Women author Louisa May Alcott's sister died from it at age 22.

Yet scarlet fever, a scourge that has caused millions of deaths throughout history and that was once described as "agonizing" and "diabolical," is now a mild illness. This formerly feared disease once sent countless children into isolation from their loved ones at so-called fever hospitals, where the young patients often contracted additional illnesses and died, separated from their families. Yet today a scarlet fever diagnosis is no cause for alarm. Modern medicine played an important part in that change, but there is more to the story.

Many lethal epidemics of scarlet fever occurred throughout Europe and North America during the 17th and 18th centuries, and such deaths were numerous in the 19th century. In fact, from 1840 through 1883, scarlet fever was among the most common causes of death for children in the United States, with case fatality rates ranging from 15 percent to 30 percent.

Making matters worse, scarlet fever sometimes occurred in combination with other potentially deadly ailments, further lowering the chances of survival. As the historian Judith Flanders put it, "Before the age of five, 35 out of every 45 Victorian children had experienced either smallpox, measles, scarlet fever, diphtheria, whooping cough, typhus or enteric fever—or some combination of those illnesses—and many of them did not survive."

In 1865, there were around 700 scarlet fever deaths per 100,000 1-year-old children in England and Wales. Despite a decline in the scarlet fever death rate, at the beginning of the 20th century the disease still caused around 350 deaths per 100,000 people of all ages.

Scarlet fever is caused by a toxin produced by Streptococcus pyogenes, the same bacteria behind the far more common ailment strep throat. Even before Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin in 1928, scarlet fever cases and deaths were falling. That was likely thanks to improvements in the population's overall health, partly due to cleaner water and better sanitation. Research suggests that better maternal nutrition also greatly increased children's resilience against the disease. Once penicillin was discovered, doctors could employ it to fight off most bad bacteria.

Scarlet fever spread easily among the poor but killed without regard to wealth or status, even slaying royalty, including queens of Denmark and Norway and a young Romanian princess. The Romantic composer Johann Strauss I lost his battle with scarlet fever in 1849 at age 45. It could kill at any age but was particularly deadly to children. The philosopher René Descartes' daughter Francine lost her life to scarlet fever in 1640 at age 5. Scarlet fever killed biologist Charles Darwin's 10-year-old daughter in 1851 and his last child, an 18-month-old son, in 1858. Scarlet fever also claimed the life of the 3-year-old grandson of oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller Sr. in 1901.

Too often, those who survived untreated scarlet fever developed rheumatic fever a few weeks later. Triggered by an immune system overreaction to scarlet fever, rheumatic fever can permanently damage essential bodily organs such as the heart and brain. Potential long-term complications ranged from an irregular heartbeat to neurological issues to heart failure. Today, thanks to antibiotics, rheumatic fever is rare.

Due to antibiotics, already-declining deaths from scarlet fever became virtually unknown. Cases of scarlet fever also became few and far between by the year 1950. The Harvard Medical School website notes the reason why scarlet fever has become so rare "remains a mystery, especially because there has been no decrease in the number of cases of strep throat or strep skin infections." Recall that the same bacteria causes all those ailments.

Sadly, cases of the disease are now rising again, although they remain far rarer than in the 19th century. Many areas of Asia began to see an increase in scarlet fever around 2009. Starting around 2014 and especially since 2022, there has been an uptick in cases in children in Europe and, more recently, in the United States. Scientists suspect that new mutations or variants in the bacteria may fuel the return of scarlet fever as a serious problem. Thankfully, the mortality rate for scarlet fever is now less than 1 percent, as almost all cases receive antibiotic treatment.

My household's tiny scarlet fever patient has been drinking each dose of the strawberry-flavored antibiotic that she was prescribed and is on the road to recovery. I am grateful to live in an era of modern medicine and good general health, where diseases with scary, old-timey names are no longer so frightening. If only the children of the past were so fortunate.