The Unprecedented Judicial Move in the Texas Abortion Pill Decision

It’s not the FDA’s job to tell doctors what to do.

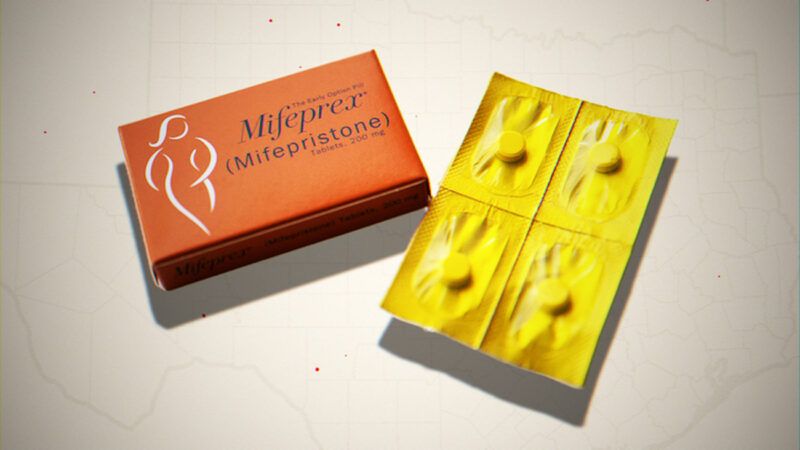

Last Thursday, Judge Matthew J. Kacsmaryk ordered the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to pull the abortifacient mifepristone from the market after 23 years of generally safe and effective market access. The opinion's activist tone and questionable reasoning have been discussed ad nauseam, but one tidbit has been missing: Kacsmaryk demanded an unprecedented degree of federal intervention in medical regulation.

Commerce Clause case law has drawn a fine line between federal regulation of medical devices —which Congress generally can regulate—and regulation of medical practices—which Congress cannot. The Constitution vests authority in Congress "to regulate Commerce…among the several States," and the Supreme Court is deferential to Congress' choices so long as Congress meets some minimum requirements. Under current case law, even "purely local" activities like growing wheat for home consumption may be reached by Congress if the aggregate effect of all home wheat farming "substantially affects" interstate commerce.

While the aggregation principle might seem unlimited in theory, there are at least some limits the Court has drawn. In the cases of United States v. Lopez (1995) and United States v. Morrison (2000), the Supreme Court clarified that the activity in question must be "economic or commercial"—relating to manufacture, production, distribution, shipment, advertisement, or transaction of goods or services. In Lopez, a federal ban on possessing guns near schools was struck down because it's silly to say mere possession of guns near schools is commercial or economic. In Morrison, a federal cause of action for sexual assault was struck down because sexual assault isn't economic or commercial in any meaningful sense. The remedy in both cases was for states to pass their own laws. This is straightforward because criminal law and public safety are primarily state issues.

Another limit was introduced in National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) v. Sebelius (2012), the case that determined the fate of the Obamacare individual mandate. The Court acknowledged the breadth of Congress' Commerce Clause authority but observed that Congress had never regulated economic inactivity. Congress had the power to regulate commerce as it exists, not to compel it into existence.

But Chief Justice John Roberts went further: "No matter how 'inherently integrated' health insurance and health care consumption may be, they are not the same thing: They involve different transactions, entered into at different times, with different providers." In other words, what you transact in, when you transact, and with whom you transact matter for Commerce Clause analysis. These questions matter because they support an additional limit to the Court's Commerce Clause jurisprudence: Congress can regulate medical devices but has never actively regulated medical practice.

The Supreme Court recently addressed this distinction in Gonzales v. Oregon (2006). Under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), the federal government may authorize doctors to prescribe controlled substances for medicinal purposes. Under a Department of Justice regulation, prescriptions must be issued "for a legitimate medical purpose by an individual practitioner acting in the usual course of his professional practice." But Oregon had defined its scope of legitimate medical practice to include physician-assisted suicide, to the chagrin of then–Attorney General Alberto Gonzales. Could the federal government under the CSA override a state's definition of what a "legitimate medical purpose" was or what the "usual course of…professional practice" meant?

The Supreme Court said no and distinguished federal regulation of access to drugs, substances, and devices, on the one hand, and how doctors used those drugs and devices on the other hand. Congress has regulated pharmaceuticals since 1906 and policed recreational drug use since 1909 but has avoided regulating the practice of medicine itself. But defining the appropriate standard of care is historically a matter of state concern. Though the statute's plain language could have justified Gonzales' regulation, the Court demanded explicit authorization before breaking from longstanding practice and respect for state prerogatives.

While Gonzales v. Oregon was ostensibly a case about statutory interpretation, the constitutional question was lurking in the background. Justice Clarence Thomas pointed out that a year prior, the Court ruled the other way in a nearly identical case called Gonzales v. Raich. California had legalized the cultivation of small amounts of medicinal marijuana for personal consumption. But the Court said Californians following California law could still be prosecuted by the federal government under the Controlled Substances Act. The Court reasoned that Congress could prohibit purely personal cultivation of medicinal marijuana if it "enacted comprehensive legislation to regulate the interstate market in a fungible commodity" and it would be "necessary and proper" to do so to avoid a "gaping hole" in Congress' "closed regulatory system."

Why did Oregon win when California lost a year prior? Because Gonzales v. Oregon (2006) was about professional practices and Gonzales v. Raich (2005) was about substances and devices. This distinction is one Justice Thomas ought to appreciate: He has already suggested in Gonzales v. Carhart (2008) that the federal government cannot regulate how doctors perform abortions under the Commerce Clause and has more recently proposed to limit Raich in other ways.

Distinguishing professional courses of conduct from other federal regulatory prerogatives is also a longstanding principle of federal law. The gist appears to be that unless doctors are dealing drugs, fixing prices, or using government power to muscle out competition, the federal government can't tell doctors—or other so-called learned professionals—what to do.

The Court even said this outright in United States v. Oregon State Medical Society (1952). A district court ruled that the intrastate practice of medicine, constitutionally speaking, was not interstate commerce. Going further, the Court held that the intrastate sale of prepayment plans for medical services—a kind of insurance—wasn't interstate commerce either. And even though there were payments made to out-of-state medical providers, the initial registration for prepayment plans wasn't interstate commerce either. Because the out-of-state payments were few, "sporadic and incidental," and presumably made on behalf of Oregon-resident policyholders, the initial sale of insurance plans wasn't interstate commerce. The Supreme Court found this reasoning persuasive and affirmed the decision. Oregon State Medical Society might seem like a forgettable footnote sunk below a rising tide of federal economic power, but its reasoning lines right up with Gonzales v. Oregon (2006) and NFIB v. Sebelius (2012).

When Kacsmaryk ordered the FDA to pull mifepristone from the market, he called for unprecedented federal intervention in medical practice as well. When the FDA approves drugs for market, it relies on a great many nonidentical studies to get a big-picture understanding of how safe and effective a product is. In some U.S. trials, the FDA relied upon required courses of conduct like checking for fetal age and ectopic pregnancies via transvaginal ultrasounds prior to giving women mifepristone. But when the FDA approved the drug for market, it determined that less invasive methods of identifying fetal age and ectopic pregnancies would be fine. In its briefing to the trial court, the FDA stated that it thought it inappropriate "to mandate how providers clinically assess women for duration of pregnancy and for ectopic pregnancy."

Kacsmaryk fumed that the FDA should have done more to tell doctors how to do their jobs. But where does the FDA, which only says which drugs are safe for market use, get the authority to regulate how doctors use those drugs? Kacsmaryk's decision repeats what later proved to be one of Roe v. Wade's (1973) biggest flaws: turning the judiciary into an "ex officio medical board with powers to approve or disapprove medical and operative practices and standards throughout the United States." After Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization last year, some activist judges would like to keep it that way.

The 5th Circuit has halted much of Judge Kacsmaryk's decision while the case is appealed. Under the FDA's 2000 approval of mifepristone, qualified physicians could dispense the drug to terminate pregnancies under 50 days gestation if there were three in-person office visits under the supervision of a qualified physician and reporting of all adverse events. The 5th Circuit upheld the 2000 FDA approval but blocked the FDA's later actions which further loosened mifepristone access.

How this will play out on appeal is still an open question. The discussion is likely to center on arcane and technical matters of federal courts' jurisdiction and administrative procedure. FDA efforts to limit the marketing of drugs for off-label purposes have raised First Amendment questions, but it's the Commerce Clause that's the source of the federal government's regulatory authority. And on that the Supreme Court has been consistent: The federal government can regulate drugs, but states regulate doctors.