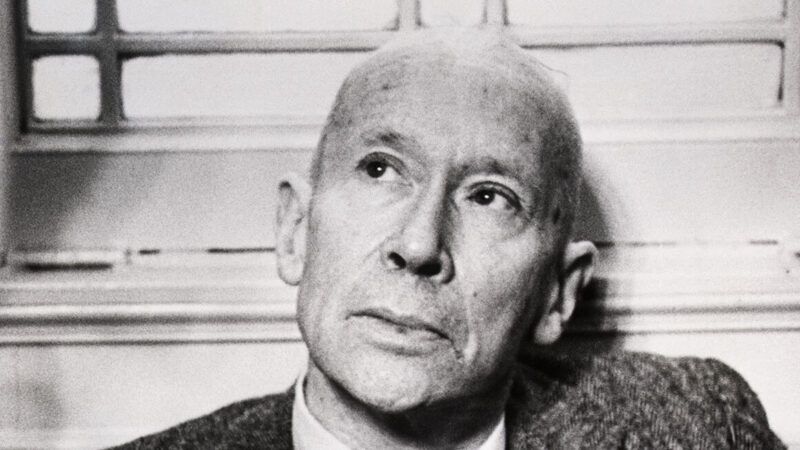

E.E. Cummings Celebrated Libertarian Utopia

His most popular book, The Enormous Room, was recently reprinted for its 100th anniversary.

The Enormous Room, by E. E. Cummings, New York Review Books, 288 pages, $16.95

Exactly a century after it first appeared, E.E. Cummings' novel The Enormous Room has been republished, reminding us that its author may have been the most profoundly libertarian writer in American literature. Beginning as a critic of authoritarian social situations, he wrote here mostly about his imprisonment in a French military detention camp at La Ferté-Macé during World War I. Eccentric and yet evocative, this classic is no less visceral a century later.

As a congenital free spirit, Cummings felt confined more than most. "The right-hand long wall contained something like ten large windows, of which the first was commanded by the somewhat primitive cabinet," he wrote. "There were no other windows in the remaining walls; or they had been carefully rendered useless. In spite of this fact, the inhabitants had contrived a couple of peep-holes—one in the door-end and one in the left-hand long wall; the former commanding the gate by which I had entered, the latter a portion of the street by which I had reached the gate. The blocking of all windows on three sides had an obvious significance: les hommes were not supposed to see anything which went on in the world without; les hommes might, however, look their fill on a little washing-shed, on a corner of what seemed to be another wing of the building, and on a bleak lifeless abject landscape of scrubby woods beyond—which constituted the view from the ten windows on the right."

Published before Cummings turned 30, The Enormous Room became his single most popular book. On the back of this new edition is an encomium from T.E. Lawrence, a.k.a. Lawrence of Arabia: "From it I knew, more keen than from my own senses, the tang of herded men, and their smell. The reading is as sharp as being in prison, for all but that crazed drumming against the door which comes from solitary confinement." (When Lawrence reminds us that he too had been imprisoned, we note, by contrast, that few contemporary writers had a similar nasty experience.)

The best parts of The Enormous Room are Cummings' memories of other prisoners, each uniquely portrayed. For example: "Celina Tek was an extraordinarily beautiful animal. Her firm girl's body emanated a supreme vitality. It was neither tall nor short, its movements nor graceful nor awkward. It came and went with a certain sexual velocity, a velocity whose health and vigour made everyone in La Ferté seem puny and old. Her deep sensual voice had a coarse richness. Her face, dark and young, annihilated easily the ancient and greyish walls. Her wonderful hair was shockingly black. Her perfect teeth, when she smiled, reminded you of an animal. The cult of Isis never worshipped a more deep luxurious smile. This face, framed in the night of its hair, seemed (as it moved at the window overlooking the cour des femmes) inexorably and colossally young. The body was absolutely and fearlessly alive. In the impeccable and altogether admirable desolation of La Ferté and the Normandy Autumn Celina, easily and fiercely moving, was a kinesis."

He adds: "The French Government must have already recognized this; it called her incorrigible."

Notwithstanding his gut anarchism, Cummings did not write political polemics. He didn't sign petitions or march in the streets. The only sign of his "activism" that I can find is a 1948 letter to his daughter where he mentions working with "Margaret Dasilva, widow of Carlo Tresca, America's leading (murdered just a few years ago in NYC City by the USSR) anarchist."

Yet the anti-authoritarians recognized Cummings as one of their own. In his classic 1929 Anthology of Revolutionary Poetry, the anarchist editor Marcus Graham reprinted Cummings' "Impressions," with these closing stanzas:

in the mirror

i see a frail

man

dreaming

dreams

dreams in the mirrorand it

is dusk on eartha candle is lighted

and it is dark.

the people are in their houses

the frail man is in his bed

the city

sleeps with death upon her mouth

having a song in her eyes

the hours descend

putting on stars….in the street of the sky night walks scattering poems.

Here and elsewhere, Cummings celebrated a libertarian utopia in which no one invades anyone else's life. This is also the subject of another, more familiar Cummings poem known only by its opening line: "anyone lived in a pretty how town." Even during the 1930s, he was nobody's fool.

This centennial reprint from New York Review Books is peculiar. As far as I can tell, its text reproduces what has long been available, initially from the legendary publishing firm Boni & Live-right, later from the Modern Library, later from other reprinters, some of which publish sloppily. It does not acknowledge the "typescript edition with illustrations by the author" that Liveright published in 1978.

The 1978 edition is superior in several respects. First of all, it includes the sketches prepared by Cummings himself, as much a visual artist as an author who illustrates his text in complementary ways. Second, it restores many French phases and, in a further departure that its author intended, prints them without the customary italics for languages other than English. Cummings' typescript also makes the stylistic choice of eliminating the spaces following commas. The typescript edition has other additions, including an introduction written by the young author's father, then a prominent minister, who describes the efforts to get his son released from prison.

The Modern Library edition, by contrast, includes a 1932 preface by Cummings that is oddly not reprinted here, even though it has this marvelous passage about the Soviet Union: "Russia, I felt, was more deadly than war; when nationalists hate, they hate by merely killing and maiming human beings; when Internationalists hate, they hate by categorying and pigeonholing human beings."

Cummings never again wrote a popular extended prose text. For his later European adventure—his 1931 report on Soviet Russia, EIMI—he favored a more liberating prose, exemplifying stylistic deviance in his critique of a society that cracked down on any and every sort of deviance. But it resembles The Enormous Room in one important respect: EIMI is a dispatch from a prison that was an entire society.