The End of Astronauts: Should We Send Robots to Space Instead?

Robots don't get cabin fever, develop cancer from cosmic radiation, miss their families, or go insane.

The End of Astronauts: Why Robots Are the Future of Exploration, by Donald Goldsmith and Martin Rees, Harvard University Press, 192 pages, $25.95

If the vast potential of outer space excites you but the cost of exploring it does not, The End of Astronauts is for you. The book imagines a future where frugal humans can have their cosmic cake and eat it too—as long as they don't mind robot bakers.

Notwithstanding their provocative title, science writer Donald Goldsmith and astronomer Martin Rees are not pessimistic about or opposed to space exploration. They just think robots should do most of the work, because robots are less needy than people, gentler on extraterrestrial ecosystems, and cheaper.

In keeping with their preference for cold machines, the authors are unmoved by the tautological romanticism that says we should go to space in order to go to space. They wave off President John F. Kennedy's famous 1962 declaration that we "choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things not because they are easy, but because they are hard."

Goldsmith and Rees are likewise unconvinced by the argument that human beings are hard-wired for space exploration. And they wonder why, if a multiplanetary existence is humanity's "destiny," we must rush to accomplish that goal now.

Stern actuaries, Goldsmith and Rees bring up such irritating considerations as cost. They note that the Hubble Space Telescope, which has captured pictures of a supernova 650 light years from Earth, could have been replaced seven times for the same amount of money that America and Europe spent on five manned repair missions. Choosing manned missions over satellite launches, they say, "reminds us that our 'sunk costs' prejudice would prevent us from choosing the replacement option so long as the repair option, even if somewhat more expensive, remained viable." As they note elsewhere in the book, such cost comparisons seldom include a ledger entry for the dollar value of an astronaut's life.

The authors are equally unsparing in discussing the International Space Station, "probably the single most expensive artifact humans have ever made." Yes, they say, it has produced "scientific and technical results," but "its return on investment has been far less than the payoff from robotic missions." The space station has been orbiting the Earth for 30 years and is now old hat, which is why it captures headlines "only from a malfunctioning space toilet in 2019 or from stunts such as the Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield's rendition of a David Bowie song with guitar accompaniment in 2020."

If they have it in for the space station and for dear old Hubble, you can imagine how Rees and Goldsmith feel about sending people to Mars or back to the moon. They go long on these topics, lazing in minutiae about exit velocities and gravity wells. If you're a fan of manned space missions, these sections may feel like someone is waving a decadent dish under your nose. The moon, they inform us, is an ideal launchpad for Mars missions as well as a potential source of helium-3 and water. And the fossil and soil records on Mars could be the key to understanding how planets die—if, that is, they don't contain microscopic life.

But none of that, the authors remind us, must be done by human beings. Robots can drive around Mars and pick up dirt. John Deere has them doing that right now in Iowa.

What robots won't do is get cabin fever, develop cancer from cosmic radiation, lose bone mineral density in zero gravity, miss their families, or go insane. A robot might die on a global broadcast, but no one would care very much.

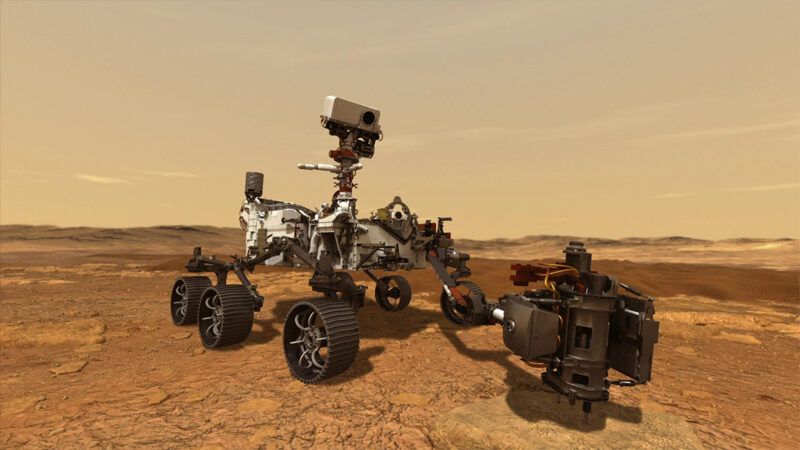

Robot and artificial-intelligence skeptics may snort at this line of reasoning, which is the book's backbone. But a pretty smart robot named Perseverance is on Mars right now, which is how we know the planet is a pocked and pimpled plane of freezing red nothingness. Do we need to spend several hundred billion dollars to have humans confirm in person that Mars looks just like it does on TV?

But we'd do more than just that! Would we? Creating a second habitable planet would be a multistep process in the way that creating a natural diamond is a multistep process for prehistoric coal. First, Goldsmith and Rees write, we'd have to give the planet a thicker atmosphere by "vaporizing the small amounts of water and much larger amounts of carbon dioxide that currently lie frozen within the polar caps." That would allow for the resurrection of the lakes and streams that once existed on Mars and, eventually, the creation of an environment that could sustain plants, which, "after five hundred or a thousand years, could make the Martian atmosphere," currently 95 percent carbon dioxide, "rich in oxygen."

The book's case against human space exploration also touches on the epistemic dangers of "contaminating" the Martian ecosystem, which could lead to an astronaut's accidental collection of his own DNA. This, in turn, might leave Earth's best and brightest unable to conclusively rule out that some kind of human had already lived on or visited Mars. That argument is not the book's strongest moment. Neither is a brief section comparing the European colonization of Asia, Africa, and the Americas with a handful of humans colonizing a desolate planet (possibly) inhabited by microscopic lifeforms trapped in layers of rock.

Despite these weak points, the book's main argument is convincing. Robots offer more bang for the buck, not just because they cost less but also because they can do a lot. If, eventually, robots are able to do nearly everything astronauts currently can, sending people into space may well become pure vanity.

Several times while reading The End of Astronauts, I recalled "American Spaceman, Body and Soul," a 2021 essay by Mike Solana, a vice president at the venture capital firm Founders Fund. "Their problem is the vision itself of an expanding, growing, heroic human civilization," Solana wrote. Solana was referring to progressives like Sens. Bernie Sanders (I–Vt.) and Elizabeth Warren (D–Mass.), who have argued that businessmen like SpaceX founder Elon Musk and Blue Origin founder Jeff Bezos should be spending their fortunes on terrestrial problems rather than exploring space. "In order to justify our present stagnation, and the committed failure of almost every person in a position of influence and authority," Solana wrote, "it must be argued there are no good men doing hard good things."

Solana, Bezos, and Musk, like many Reason readers, are space romantics, and one thing space romantics can offer that space pragmatists often don't is a spirited rebuttal to the kind of declinist thinking that says no one can dream big until America has cured its most intractable social ills. Were that argument to prevail, there would be little money (public or private) for astronauts or robots. But if we are to extend ourselves further into space, we cannot ignore what the pragmatists say. And the most pragmatic path may be both private and robotic.