Microschools Have a Big Future

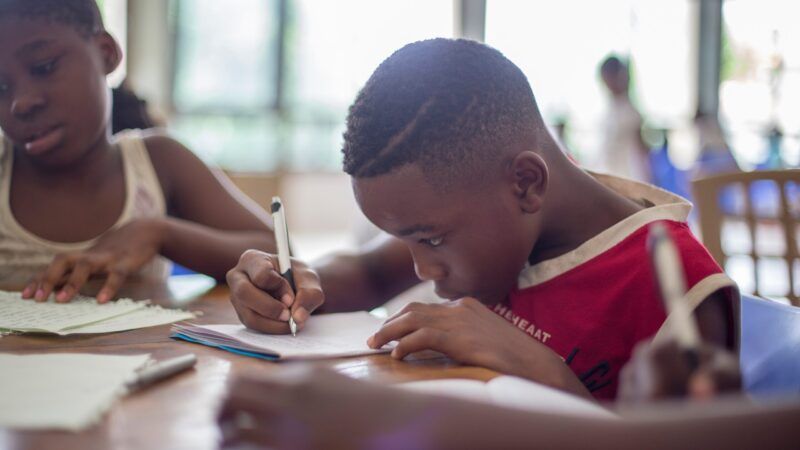

Small-is-beautiful education avoids conflicts that plague larger one-size-fits-few institutions.

What might the future of education look like? As families and students steadily migrate to learning options better poised to serve their needs than struggling traditional public schools, it's natural to wonder what's to come. But education in the future may not have any one face, and that's a good thing. Flexibility is the name of the game as parents experiment with homeschooling, private schools, microschools, charter schools, learning pods, and combinations of all of the above as they move beyond floundering institutions.

The challenges are obvious as even the most risk-averse school officials move past closed classrooms and distance-learning plans in an effort to keep public schools open, only to run afoul of new challenges.

"While many officials and parents nationwide push to keep kids in school and away from remote learning, Omicron has left many schools short of the essentials needed to operate, like teachers, substitutes, bus drivers, cafeteria workers—and sometimes students themselves," The Wall Street Journal reported this week.

Shortages of students? Well, yes. After nearly two years of uncertainty and lost ground, a lot of families have turned their backs on the schoolhouse doors. Maryland's public schools are only the latest to report that the exodus of students seen last year continued this year, with enrollment down 28,000 from pre-pandemic figures. Disappointment in public schools cuts across race and class lines as American families look for something better for their kids.

"While the learning pod movement swept across the country's white, affluent areas during the pandemic, outrage grew as the pandemic afflicted Black communities more than any other group and academic gaps grew along racial lines," The 74, an education-oriented publication, noted this week. "The moment became an opportunity for the Black Mothers Forum to formally launch and recruit for their own schools in January 2021."

Based in Phoenix, Arizona, the Black Mothers Forum launched a network of microschools to "tear down barriers to academic excellence due to low expectations, and break the cycle of the school to prison pipeline" as the group's mission statement reads. Originally partnered with Prenda, an Arizona-based company that specializes in getting microschools launched and operating, Black Mothers Forum has since converted its outlets to charter schools, which subjects them to greater regulation, but also comes with funding so that they don't have to charge tuition. The organization's efforts won the attention of Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey (R), who granted it $3.5 million to expand the network of microschools from seven to 50. Their success is reflected in similar efforts across the country.

"Micro schools are the latest schooling alternative to take off as more teachers and parents are becoming fed up with schools keeping their classrooms closed and students falling behind," Fox Business observed earlier this month.

If the term "microschools" confounds you, that may be because it came to the public's attention only recently, along with "learning pods," as families scramble to educate their children amid COVID-19-fueled disruption. The dividing line between the two is more than a bit fuzzy, and they overlap with other categories of learning, such as homeschooling co-ops and even one-room schoolhouses.

"As their name suggests, microschools, which serve K-12 students, are very small schools that typically serve 10 to 15 students, but sometimes as many as 150," Barnett Berry, a research professor of education at the University of South Carolina, specified in a September 2021 article. "They can have very different purposes but tend to share common characteristics, such as more personalized and project-based learning. They also tend to have closer adult-child relationships in which teachers serve as facilitators of student-led learning, not just deliverers of content."

Meridian Learning, a microschool advocacy group, insists that learning pods are "temporary alternatives" for stranded families while microschools are "professional, long-standing" approaches rooted in homeschooling. But rather than get hung up on terminology, it's better to emphasize that these are all ways of describing flexible alternatives to rigid institutions that struggle in good times, founder at a hint of crisis, and become battlegrounds for disagreements about what should be taught. What matters is that children learn, not the details of the settings in which they absorb lessons.

"Grassroots microschools serve a variety of children and families, including those in underserved areas and those whose needs are not being met by the current system," Meridian adds.

Because the emphasis is on teaching kids through whatever approach works in different situations, guidance for starting up a microschool/learning pod/homeschooling co-op, etc. tends to be on the vague side. "Some microschools are run out of homes. Others build their own facilities. Shared space can often be rented from churches–which tend to remain vacant during the week–at a very low rate," advises Microschool Revolution, which connects school founders with funding.

Advocacy groups like Meridian Learning and companies such as Prenda offer guidance, structure, and teaching materials. Other microschools evolve out of homeschooling networks in which families share expertise to teach each other's kids. The results might be organized as private schools, charter schools, schools-within-public-schools, or homeschooling co-ops. That means the rules to which they're subject vary, although many fly under the radar as ad-hoc arrangements. Again, the emphasis is on small, flexible environments that address the needs of specific students.

If that sounds confusing, it's no more so than any other freedom to make your own arrangements. It also can't be any more confusing than what The Wall Street Journal describes as "low-grade chaos" prevailing at public schools struggling to adapt to lingering health challenges and labor shortages, and often failing to satisfy anybody in the process.

"Some are saying the guidelines are too strict, some are saying the guidelines are too lenient. It's almost a Catch-22. You do one thing for one, then you get heat from the other," one high school principal told the newspaper.

By serving students assembled from like-minded families, microschools and similar small-is-beautiful approaches avoid conflicts over policy as well as other disagreements that plague larger one-size-fits-few institutions. The one thing they have in common is their mission to educate students in a focused setting. The future of education may well be small, in a very big way.