The Anarchic Interlude

In 1990s Prague, wonderful things happened in the chaotic space between the end of communism and the rise of its replacement.

Reason's December special issue marks the 30th anniversary of the collapse of the Soviet Union. This story is part of our exploration of the global legacy of that evil empire, and our effort to be certain that the dire consequences of communism are not forgotten.

"Shhhhh!!!" I slurred to the Amsterdam-based American jazz pianist who was at that moment bellowing out a profane interpretation of the "Star-Spangled Banner" while swigging from a bottle of cheap Moravian wine at around 3 a.m. on a weeknight in Prague's Old Town Square. It was August 1990, nine months after Czechoslovakia's Velvet Revolution, and I had just spotted two armed men in red-accented military fatigues veering in our direction with sudden interest. My lubricated 22-year-old brain, facing the prospect of confrontation with the Red Army, lapsed into a panicky pop culture tailspin—War Games, Red Dawn, Amerika…run!

The expat ivory-tickler, seasoned enough to have dodged the Vietnam draft, did not share my apprehension. "WEEEeeeeLLLL," he offered, in leery adaptation of Steve Martin's 1970s catchphrase, middle fingers beginning to jab defiantly upward, "FfffffUUUuuuUCCCKKK…YOUUUUUUUUUUUU!!!" I blinked dumbly in shock, too paralyzed to thwart the ensuing (and in retrospect inevitable) soldier-directed Heil Hitlers.

You never know while living through history how things will turn out in the end. Prague felt free (if poor and polluted) that summer, but the same had seemed true in the summer of 1968, until very suddenly and violently it was not. Warsaw Pact troops had brutally extinguished similar liberatory flickers in 1981 Poland and 1956 Hungary. Mikhail Gorbachev had just been elected to a five-year term as president of the Soviet Union, was vowing to give communism "the kiss of life," and in five months' time would dispatch tanks to crush protesters in Vilnius, Lithuania.

So I clutched my passport and steeled myself for the gulag. Instead, one of the soldiers smiled, made the universal tilted-head-on-two-hands people are sleeping gesture, and pointed toward the bedroom windows overlooking the magnificent plaza. The piano player threw a friendly arm around the grunt's shoulder and planted a sloppy kiss on his cheek, then we stumbled off cackling into the night.

Breaking the Spell, Exploring the Wreckage

Weird and wonderful things spring up in the untended spaces between an old system collapsing and a new one taking its place. Totalitarian structures don't just vanish overnight—laws, bureaucrats, cops, and even politicians can remain the same for months and years on end. But the spell of their power is broken, and everyone knows it. When authorities no longer have authority, the resulting atmosphere can be dislocating—and euphoric.

Prague had many claims to being the life of the post-Party party. Czechoslovakia's fairy-tale revolution, more than the others in what was still called the East bloc, had been spearheaded by high school and college students, who now streamed into the big city to gorge on previously forbidden cultural fruits. Their president, a chain-smoking playwright/dissident who had spent much of the 1980s in jail, delighted in welcoming international icons into the Mitteleuropa mosh pit: Lou Reed, the Rolling Stones, the Dalai Lama, etc. The capital of Bohemia, after an unnatural, four-decade attempt to stifle the same culture that helped produce Antonín Dvořák, Franz Kafka, Karel Čapek, Miloš Forman, and Jan Saudek, was ready to release some pent-up expression.

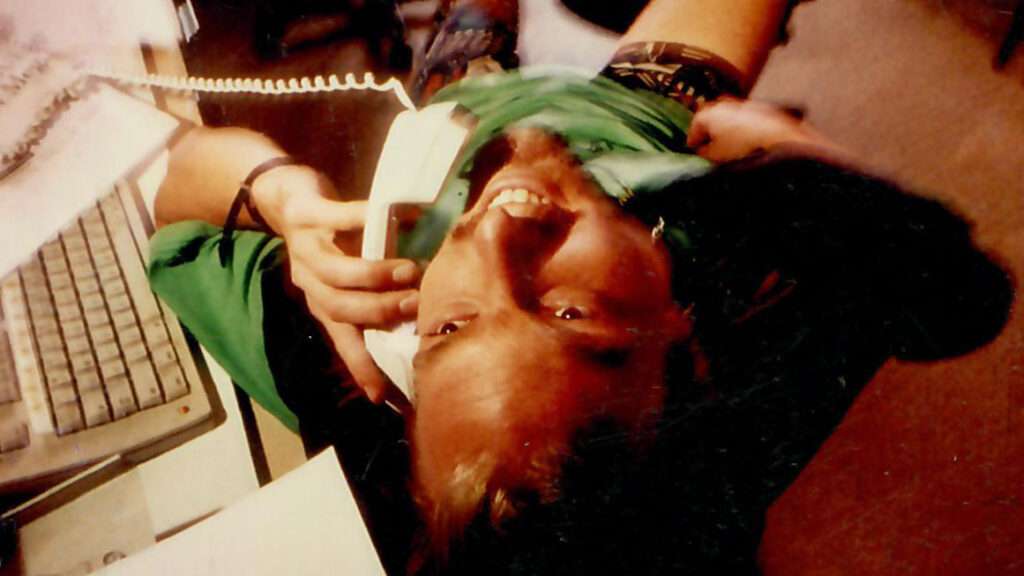

Rushing in from the other side of the breach were thousands of bushy-tailed Westerners like me—raised in the dull, horizonless stalemate of the Cold War, seeing only a big black smudge on the map marked "Iron Curtain," until that magical month of November 1989 when the veil was lifted and the bugle sounded. Imagine a world before the commercial internet, where your best travel information came from annual guidebooks that had been rendered obsolete overnight: Every peek down a neglected alleyway carried the promise of fantastical discovery. Especially in a city that beautiful, with beers that cheap and bars that packed with people your age who had just toppled totalitarians without firing a shot.

So what did these two worlds do upon colliding, now that governments no longer artificially obstructed their paths? They explored. And played, and created.

Elephants in the Stalin Space

Much of the Prague skyline at the time was choked with soot and scaffolding. The dingy latticework outside the famous (and famously grumpy) U Vejvodů pub, around the corner from the office of the English-language newspaper some friends and I launched in March 1991, was rumored to date from the 1950s. The physical deterioration of arguably Europe's most architecturally significant never-bombed metropolis—the entire city center was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1992—had posed a conundrum for the Communist government that owned and mismanaged most property: How to keep up appearances, and appeal to tourists with much-needed hard currency, without soaking up too many scarce resources?

Enter the Linhart Foundation. Or more accurately stated, enter the dissident architects who, having been barred from creating their own works, were grudgingly allowed in the 1980s to spruce up some of the regime's grimy buildings and crumbling statues, gaining invaluable knowledge along the way about what was underneath all that scaffolding. When the commies were driven from power, this underground group of artists and engineers formed one of the most potent—and mischievous—countercultural organizations in post-revolutionary Prague, constantly probing and colonizing abandoned spaces, testing the limits of the law, and igniting "actions" that mesmerized all those lucky enough to take part.

The Linharts (named after a flying elephant, because why not?) were officially organized as a foundation about 10 days before my Old Town Square episode, with the initial, urgent aim of getting the city some damn rock clubs. Czechoslovakia was only then beginning the process of removing the state's central role in commerce, sorting out property rights, and rewriting the legal code to enable the most basic of enterprise. Back then all the grocery stores were still called "groceries" (potraviny) and fruit and vegetable stores were "fruits and vegetables" (ovoce a zelenina), and you'd be lucky in the latter to find anything besides potatoes and onions come November.

The laws as written required countless stamps from various sluggish ministries to launch much of anything, let alone an undertaking as novel and complicated as a rock club, so the Linharts started acting first, asking for permission later. That summer, the architects stole a peek behind the padlocked iron doors guarding a vast, labyrinthine bunker under the hilltop pedestal where the world's largest statue of Josef Stalin once stood. The dank "Stalin Space," as it soon would become known throughout Europe, had been largely forgotten, used mostly as storage for potato crates and old junk, since the monstrosity was dynamited in 1962 as part of Nikita Khrushchev's campaign of de-Stalinization.

The foundation sprang into action, sending letters—email wasn't really a thing—to 200 art weirdos in 17 countries, basically saying "Come!" To house them, an entire abandoned palace just down the hill from Prague Castle was commandeered and converted into an avant-garde squat, where one might (and did) encounter a half-naked Russian interpretive dance combo writhing and screeching around a courtyard bonfire under terrifying pink cherubs suspended on wires while a phalanx of cops paced outside threatening to shut the whole shebang down.

All that was just an amuse-bouche for the "Totalitarian Zone," a legendary two-week art happening held in the creepy caverns of the Stalin Space. As I attempted to convey in the second issue of our newspaper, the hallucinatory scene drew more than 1,000 adventure seekers daily, "and in the process captured the imagination of the local intelligentsia, writers, foreigners, politicians, artists and anarchists. Every night…offered the promise of rock bands, live pirate radio broadcasts, theatre, videos, sculpture, painting, beer and young people everywhere—all thriving amidst the asphalt shrapnel of the long-destroyed embodiment of the Biggest Brother."

And it was all technically illegal. The pirate "Radio Stalin," for example, operated on airwaves the government hadn't yet opened for private use. It incurred hefty fines…even though the first on-air interview was with none other than President Václav Havel. Such was the constant push-pull during this entertaining and fraught in-between stage of "transition": An impatient soul would kick open a door, thousands would scurry through, and flummoxed officials would unevenly enforce the letter of the law, while some of the nation's leading politicians lent moral support to the transgressors.

The Totalitarian Zone was not universally beloved. Those who were more conservative, or just unhappier with the side effects of radical system change, chafed at the lawlessness and bacchanalia. There was much grumbling in the first year or two after the revolution about all the "longhairs in the castle" amusing themselves to death and chasing utopian policy dreams (such as emptying the prisons and closing down weapons factories) while babičkas were struggling to get by on their decreasingly sufficient pensions.

But it is also true that the revelers were interested in much more than just partying. The corruptions and compromises that enabled 40 years of communism were never far out of their sights.

The art gallery in the Stalin Space included a fenced-off papier-mâché rendering of a hideous skull and bones, created by 23-year-old commie-hating provocateur David Černý, at the scale of the original Stalin statue. Černý—whose name appropriately means black, as in Czech culture's pervasive "black humor"—was already known domestically as the artist who had mounted a gold-painted East German Trabant car on elephantine human legs at the entrance of Old Town Square that summer. He would eventually reach international infamy by viciously satirizing all the countries of the European Union in a fake "group" project funded by the Czech government to mark its rotating presidency of the E.U. Council.

But before any of that, Černý would perpetrate the single most notorious and symbolic art prank of the entire 1990s, an act that would strain international relations and land Černý temporarily in jail, even while nudging people away from the path not taken during the fluxy interval between the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and the expansion of NATO.

The Pink Stink and the Road Not Taken

Just as there was no guarantee in August 1990 that the still-existing Soviet Union wouldn't crack down on its current republics or even its former satellites, it was not preordained that NATO, founded in 1949 to counteract the Soviet menace, would continue, let alone expand, after the demise of its enemy.

When Havel addressed a joint session of the U.S. Congress in February 1990, he sketched out a vision where the countries of Europe would be "responsible" for their own security and the superpowers could finally go home. "The main thing is," he said, "that these revolutionary changes will enable us to escape from the rather antiquated straitjacket of this bipolar view of the world."

In the immediate term, the task for all the newly freed states of Central Europe was getting all the Soviet troops out pronto. (Czechoslovakia would be first to accomplish that goal, marking the occasion in June 1991 with a star-studded rock concert at which the nationally revered Frank Zappa gave his final live performance.) The "Visegrád Group" of Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia next set about convincing Gorbachev to liquidate the Warsaw Pact, which was accomplished in Prague on July 1, 1991. So far, so responsible.

Havel proposed creating a European Security Commission under the auspices of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), which had played a critical role in the 1970s and '80s in pressuring communist governments to live up to their international human rights treaty obligations. "In the end, Europe would be capable of ensuring its own security," he envisioned in a May 1990 speech, "at which point the last American soldier could leave Europe, because Europe would have no further cause to fear Soviet military might."

Explained Czechoslovak Foreign Minister Jiří Dienstbier in the summer 1991 issue of Foreign Policy: "Replacing previous membership in the Soviet sphere of influence with integration into another sphere of influence would hardly improve the security situation of Central Europe."

So why was the road of European self-responsibility not taken? Critics of American foreign policy overreach tend to pin the blame on power-hungry Washington and the customer-seeking military-industrial complex, eager to expand the reach of the American-led transatlantic alliance. But that analysis absolves the cipher at the center of the story: Europe.

Shaking up a snow globe can look beautiful from the outside and exhilarating from within, but waiting for the new scene to settle can be vertigo-inducing for those who want a bit more predictability in this world. The fledgling Central European nations shared one unhappy trait: They'd all been repeatedly overrun and subjugated by larger imperial neighbors. As such, the one thing they wanted most of all after the last Red Army soldier boarded an eastbound train was a security guarantee—that the borders will no longer be breached, and that someone will come running if they are. Rebuilding after the economic and environmental wreckage of Really Existing Socialism was expensive enough without adding an arms race to the unrequited nationalist longings that were beginning to bubble up.

Our newspaper, Prognosis, was monthly back then, and our July, August, and September cover stories from 1991 tell the tale of a rapidly growing security vacuum: First the Soviet troops finish their withdrawal, then Yugoslavia begins its descent into bloody civil war, and finally a failed coup attempt in Moscow sends tremors of fear throughout the region. (Americans back home tended to imagine our time abroad as an un-interrupted carnevale. I'm here to tell you it was not.)

Havel and his counterparts had wanted to rejoin a more assertively responsible Europe, but the European Community (as it was still known) reacted to the tumult on its turf with something closer to paralysis. Member states squabbled over whether the coming E.U. needed to be "deeper" or "broader," thus delaying accession talks with the needy young upstarts in the east. World War II allies were spooked by the potential pull of a unified Germany, which then added to the anxiety by taking sides early in the already nightmarish Balkan crack-up. Much of the continent was still overreliant on Russian oil and gas, screwing with the incentives about how to deal with a wobbly Gorbachev. There just wasn't appetite for any newfangled ideas about turning the OSCE into a border-securing, tension-reducing military force.

But I think there was an additional factor pushing Central Europe's new idealists into the hoary old arms of NATO, best symbolized by the June 1991 cover story of our newspaper: "The Pink Stink."

On April 28 that year, the aforementioned enfant terrible David Černý, dressed in worker overalls and carrying a forged permit, clambered atop the "Monument to Soviet Tank Crews"—an imposing tank that had been mounted atop a 15-foot pedestal since 1945 in commemoration of the Red Army liberating Prague in the waning hours of World War II—and, with the help of a dozen friends, painted the whole thing a festive bubblegum pink. In case the emasculation wasn't obvious enough, Černý also affixed to the top of the vehicle a giant pink papier-mache middle finger. "I don't understand art which is about nothing," the artist shrugged to me after.

Cops who caught Černý mid-caper were satisfied with his permit and his cover story about preparing some fun-loving fraternal art for the coming May Day parade. (Look, anything seemed plausible in Prague back then.) And even though Černý signed his name, it wasn't until he called in with a confession a couple of days later that the bumbling police could figure out the culprit. Upon which they arrested him, for a crime called výtržnictví, which means (depending on your translator) "hooliganism," "disorderly conduct," or "disturbing the peace." That's when things escalated.

Authorities had re-painted the tank green the day after Černý's stunt, and all the requisite apologies were made to smooth the appropriate diplomatic feathers. But for many of the former dissidents who now found themselves in parliament, watching a cheeky young anti-communist rung up on the same catchall statute that had landed so many of them behind bars in the bad old days—there's a book-length 1987 interview with Havel titled Disturbing the Peace—had them seeing red.

And so on May 16, to cap off a student rally at the base of the memorial, the ladders and paint cans and overalls came out, and 15 deputies from the Federal Assembly flexed their parliamentary immunity by painting the old IS-2 attack vehicle pink all over again. "This was a vile act of political hooliganism," Soviet Foreign Minister Vitaly Churkin said the next day. Ruh-roh.

In retrospect, that might have been the moment when the anti-communist movement was decisively cloven in two, between the outsidery tricksters who could never get enough of razzing the reds—"This is the best action since the revolution!" one of the student organizers told me—and the increasingly grim-faced adults trying to navigate the realities of governance. "We were in a bad situation, because everybody likes the pink tank, but they have to deal according to the laws," district Deputy Mayor Eva Kalhousová explained to me.

Federal Assembly Chair Alexander Dubček, whose humiliation by Moscow in 1968 symbolized the imperial kneecapping of the Prague Spring, now flew back to the Kremlin to beg for forgiveness. Havel, who until then would usually wink in the direction of the scofflaws, said tersely that "the action of the federal deputies does not get my credit at all." (Privately, the president signaled he would pardon Černý if necessary, which it ultimately wasn't.)

With the honeymoon phase of the post-revolutionary period winding to a close, many of the ex-dissidents' pie-in-the-sky ideas were treated as childish things to be put away. Havel had come into office refusing to start or join a political party, preferring instead the lofty-sounding ideal of "non-political politics." (The man who would become Havel's longtime rival and tormentor, Finance Minister Václav Klaus, rushed gleefully into party formation, instantly becoming the most powerful politician in the country.) The president's philosophical meanderings about "Being," his overemphasis on Czech responsibility for bilateral historical tensions with formerly antagonistic neighbors such as Germany, his stubborn focus on the human rights violations of influential countries—all were seen as naive, even self-destructive.

With Europe unwilling to act on his security proposals, with Yugoslavia on fire, and with the Soviet Union dissolving in December 1991, Havel himself appeared to internalize these criticisms, or at least to recognize that a post-superpower vision of foreign affairs was just not in the immediate cards. "Our main problem is that we feel as if we are living in a vacuum," he told Bill Clinton on April 20, 1993, after the opening of the Holocaust Museum in Washington, where the leaders of the Visegrád Four (Slovakia having been freshly minted as an independent country) thrust alliance-expansion onto a reluctant new U.S. president. "That is why we want to join NATO."

Unlikely Entrepreneurs

One of the best parts about living near the rubble of a knocked-down wall is that there's a lot of wiggle room in the cracks. Not only do you quickly learn what scary-sounding laws are never enforced—no, you didn't really have to exchange $15 a day at the state-run tourist agency or get your passport stamped at the border every couple of months—but you also discover bizarre loopholes to exploit until the new boss wises up.

I had saved up about $4,000 before getting on a one-way flight to Paris on July 4, 1990 (the juvenile symbolism was intentional) and upon arrival in every new country would use my debit card to obtain local currency. At the main Prague bank, I noticed a low-tech wrinkle: The plastic wasn't run on anything electronic; they just made a carbon imprint on paper and handed you a cash advance. It was as if you could just…print money. From this came a healthy chunk of Prognosis' startup funds.

One of the worst parts about living in an economy basically starting from scratch is that there just isn't much of anything you want—local news, non-Turkish coffee, bagels, coin-operated laundromats, burritos, etc. So a generation of young expats who had never dreamed of running businesses started launching the things right and left, taking advantage of all that latitude before the new rules were cemented into place.

There were (and in some cases still are) expat-run coffee shops, rave clubs, literary magazines, vegetarian restaurants, New York pizza joints, one of the continent's greatest English-language bookstores, one of its dingiest pool bars, some guy named Peyton who would swing by our office every day selling homemade submarine sandwiches, and so forth. Americans expect immigrants to be entrepreneurial, to bring some of the home culture to the new place, but we don't necessarily expect them to be us.

One day another American came by our office, a wild-eyed true-crime author named John Bruce Shoemaker, who had clips from magazines like Screw. I would have hired him on the spot, but I wasn't in a hiring position that season, and so J.B., as we would all end up calling him, went on to other pursuits. Oh man did he.

One of Prague's most magnificent buildings, arguably the most spectacular art nouveau structure in the world, is the Obecní dům, or Municipal House, the living monument to the turn-of-the-century Czech National Revival. It was here in 1918 where Czechoslovakia declared itself an independent country; it was here in 1989 where Havel's Civic Forum negotiated the transfer of power from his former communist captors; it was here in 1994 where I got disorientingly stoned while listening to Allen Ginsberg rap about Sarajevo. The Czech Philharmonic plays in the building's Smetana Hall; majestic Slavic murals by the immortal Alphonse Mucha adorn the walls; even the basement pub is decorated with pastoral tileworks fine enough to make your knees go wobbly.

And for a couple of years there in the early '90s, most of this cornerstone of Czech patrimony was run like a pleasuredome…by John Bruce Shoemaker.

The specifics are too hazy and preposterous to fact check (J.B. left this mortal coil in 2010), but the general template was the familiar script across the city, country, and region: Between the collapse of communism and the erection of capitalism, between the end of central planning and the beginning of private ownership, there were still assets to exploit, markets to cultivate, and wheeler-dealers to lubricate the temporal spaces in between.

Shoemaker and his fellow Montanan Glen Emery came to town with less than $1,000 each but hustled up one of the first runaway expat restaurant successes—a Mexican joint near the Charles Bridge called Jo's Bar. The Obecní dům by then was sporadically glorious but mostly empty and run-down, as the city prepared a laborious plan for eventual restoration and development. Someone knew a guy who knew a guy, and by 1993 the Shoemaker/Emery team was invited to begin temporarily managing a few of the massive building's commercial spaces: some grand, some grisly.

If you've ever heard Nick Cave sing about how he's "feeling very sorry in the Thirsty Dog," well, that was one of the bars. Another had to be closed down when too many Czech teens were shooting up Pervitin. There were legends of 24-hour acid-trip lockdowns, sacks stuffed with cash thrown out of windows to avoid either inspectors or bag men (or both), live music pouring out of every decorative hole. And while there was something discordant about this Czech crown jewel being trampled underfoot by transnational sybarites and English-speaking locals, that building for the first time in who knows how long was also alive, teeming with celebratory cosmopolitans who were appreciative of the space, if not precisely careful with its treatment. (My shoes get sticky just thinking about it.)

Between the Big Bangs

Once the entrepreneurialism bug hits, it never really exits your system. Long after Prague reclaimed its Municipal House for renovation and more sober management, J.B. was still kicking around the city, launching and managing popular nightlife establishments. The Linhart Foundation people did eventually get their rock clubs and cultural centers—most notably the Akropolis, one of the most vibrant venues in Europe. Radio Stalin became Radio One, a market-dominating alternative station that thrives to the present day.

My little corner of the Central European startup universe, English-language newspaperdom, ended up seeding a disproportionate number of early dot-com pioneers back in the United States. Prague colleagues Ken Layne and Charlie Hornberger started one of the first internet newspapers in 1996 (Tabloid.net); Layne would later work off and on for the Gawker empire of Nick Denton, himself the dean of the Budapest foreign correspondents in the early 1990s. Budapest Business Journal editor Henry Copeland would go on to found the first blog advertising company; Budapest Week founder Rick Bruner was an even earlier developer of online ads. Moscow's bad boy The eXile unleashed onto the world Matt Taibbi, and even the humble Baltic Times gave us eventual BuzzFeed editor in chief (and current New York Times media columnist) Ben Smith.

Our generation, known for the past three decades as "X," has three distinct straddling points in the modern human timeline: We remember before and after the end of the Cold War, we remember before and after the beginning of the World Wide Web, and we remember before and after 9/11. All three events reordered life on this planet so profoundly that words are effectively helpless. Each Big Bang has also had its backlash: the reappearance of an imperialist Russia (with tentacles spread back into Central Europe), the internet's shift in public perception from liberating force to omnipotent ensnarer, and most recently the ignoble ending of a mostly pointless 20-year war in post-9/11 Afghanistan. We're still desperately trying to figure all this stuff out.

But those of us who went exploring in the newly opened 1990s can testify that there once was a time when you could buy a one-way international ticket in cash without arousing suspicion or entering a database, where the only way for your family to reach you was at the open letterbox marked poste restante in some city's main post office, where the next train stop was a genuine mystery only hinted at by a couple of terse paragraphs in a dog-eared guidebook. I'm not saying that we were more free then, but there were certain advantages and experiences that have been lost and are worth remembering.

Lost, too, were opportunities, in literally every country, for a kind of moral inventory of how the Cold War, even on the most righteous of flanks, corrupted our belief systems and activity. Americans in the political class could have spent the '90s confessing their prior misjudgments, publicly recalibrating their views, and rediscovering humility in the face of events literally no one predicted. Instead, most just dutifully trudged on to the next political fight, took in precious little information after the secret police archives opened up, and slowly began preparing for the next "existential crisis." After beginning the decade with heated political debates about Washington's role at "the end of history," a bipartisan elite consensus by the turn of the millennium agreed with (Czech-born) Secretary of State Madeleine Albright's characterization of America as the "indispensable nation." We are still living with the consequences of that choice.

Albright's ancestral home during the early '90s was a fixation of both the gushing international media—I was profiled by 60 Minutes, NBC's Prime Time Live, the BBC, the L.A. Times, Editor & Publisher, and Details magazine, among others—and of the grousing expatriate communities nearby. (The acclaimed Arthur Phillips novel Prague is actually about early '90s Budapest, whose characters are alternately disdainful and jealous of the Golden City's glow.) Those of us who lived in that bubble, especially during our mixed-up 20s, were perpetually haunted by the question of whether we could attain anything like our pecking-order placement, or at least our degree of notoriety, back home in the "real world." I was surely not the only slingshottee from Central Europe newspapers to American online media who came to see the calamity of that miscalculation.

The 1990s ushered in more freedom than any decade the planet has ever seen. Released in the First World from the grip of the superpower struggle and in the Third World from local despots propped up either by Moscow or by Washington, human beings just did their own thing, which largely turned out not to be about white-knuckle politics or life-and-death international relations. It was about normal, glorious, human interaction. If things got a bit manic and experimental around the edges, well, good.

Most of us are fortunate enough now to live well outside the shadow of totalitarianism. But authority—surveillance, controls on our movement, intrusive policing—is still around us, and on the grow. Tribal politics are demanding more of our attention, turning neighbor against neighbor. Oh, the places we could go if we busted down some walls, allowed for more untended spaces, and relished our own untethered personal responsibility!

We are meant to build new stuff, meet new people, and probe the outer perimeters of any attempts to fence us in. In hindsight, the proper question in early '90s Prague was not "Should this be more like real life?" but "Shouldn't real life be more like this?"