HBO Documents the Tragic Tale of Lucy, the Chimp Raised Like a Human

An experiment to see if nurture could overcome nature did not end well.

Lucy the Human Chimp. Available Thursday, April 29, on HBO Max.

A couple of weeks ago on the distant shores of satellite TV, I stumbled upon an old favorite of mine, Congo, a 1995 film about a safari in search of King Solomon's fabled diamond mines that runs afoul of a tribe of killer chimpanzees. (Back in the day, it scared a visiting granddaughter catatonic and I had my first full night's sleep in weeks.) The movie's MacGuffin was a sweet, lab-raised chimp who could use sign language to talk through a computer doo-hickey—and who knew the mine's location.

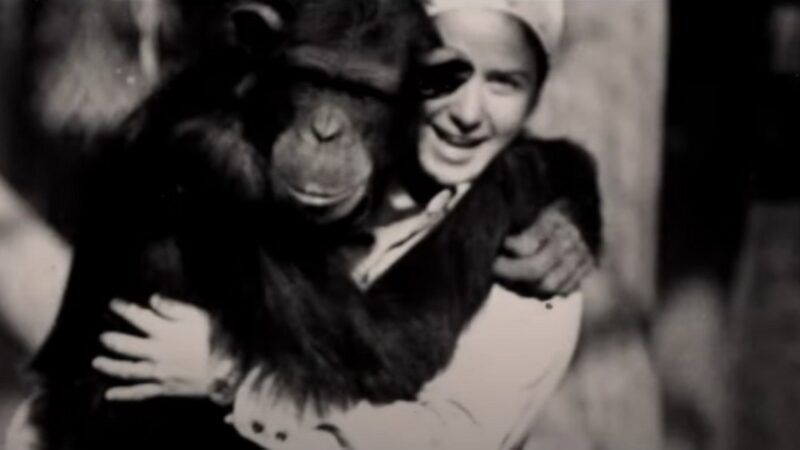

I'm guessing the people behind Congo knew something about Lucy, a very real chimp who had her 15 minutes of fame back in the 1970s—book, Life magazine story, episode of Wild Kingdom, everything but her own reality show. Lucy, raised by a (human) psychologist almost from birth, also learned sign language, not to mention gin-and-tonics—she squeezed the lime with her teeth—along with Playgirl magazine and all the other stuff that makes humanity so special. (Though when Lucy was taken to a drive-in showing of Planet of the Apes, she was merely bored.)

But when she turned rambunctious upon reaching puberty, Lucy was shipped to a chimp reeducation camp in the Gambian jungle, where she had a difficult time of it and was eventually killed by poachers.

The poignant and sometimes disturbing HBO Max documentary Lucy the Human Chimp updates Lucy's tale, and even more so that of Janis Carter, the human companion who accompanied her back to Gambia for a three-week acclimation trip that stretched into forever. The program inevitably raises some issues about human anthropomorphism and scientific indifference to animal welfare. But mostly it's a meditation on the difficulties attendant upon falling in love across species lines, something already touchingly familiar to anybody who saw Willard.

Carter was a University of Oklahoma grad student hired to feed Lucy and clean out her cage. Carter was warned not to attempt any BFF stuff; Lucy was already showing some aggressive tendencies, jumping through closed windows and even breaking out to loot the refrigerator of the neighbors next door. Sticking a finger into her cage was less likely to be regarded as a friendly gesture than as an offer of a fast-food sample.

Moreover, there was a daunting intellectual gap between the two; Lucy knew 120 words of English, apparently well beyond the vocabulary of the average University of Oklahoma grad student. When Lucy grew frustrated by the slow speed of Carter's signing, she repeatedly flashed the signal for "stupid." Nonetheless, their long afternoons together eventually developed into a friendship. Carter put her back against the cage and allowed Lucy to groom her for vermin; then they reversed positions.

Lucy had been snatched from her mother, a performer in a ramshackle Florida roadside zoo, when she was just two days old and raised as if she were human, a calculated attempt to sort out nature from nurture in chimp behavior. At home, she slept on a Beautyrest mattress, ate oatmeal with raisins for breakfast, then washed it down with coffee and Tang. That made her relocation into a jungle camp nearly impossible. There she lost weight and great patches of her hair fell out.

Carter made the flight to Gambia just to help with a three-week transition, but her alarm at Lucy's condition made her postpone return to the United States for two weeks, then another three months. In reflective moments, when she wasn't eating grimy leaves and twigs from the jungle floor and grunting in pretend-pleasure to convince Lucy that this stuff was food, Carter wondered what she was doing, missing classes and rent checks back home. "I had a dog," she mused. "I had a boyfriend." As her funds ran low, she moved out of a hotel room into a jungle treehouse. In an even more profound inversion, when she took Lucy and three other rescue chimps out of the camp and onto a jungle island, Carter slept in a cage ("I don't think anyone told me about the leopards") while the chimps spent the night on the roof—unleashing a rain of excreta onto her through the bars whenever they heard a scary noise, which was practically all night long.

Years passed. Lucy was not acting much more like a chimp, but Carter was. She let her correspondence with the outside world lapse and spoke little English other than frequent and futile repetitions of "Lucy—food—eat." Carter lost all track of time aside from the seasons and never even thought about returning to the outside world. "I don't know if I ever became a chimp, so to speak," she says in an interview taped for the documentary. But she sure takes a long time to answer.

When six years passed, the chimps themselves let Carter know—unambiguously and heartbreakingly—that it was time for her to leave. Even then, she just moved across the river and continued watching them from afar. Today, more than four decades later, her hair slack and gray, she still sleeps in her old cage on the island, tending a steady stream of rescue animals. Nature vs. nurture remains an open question for chimps, and perhaps for their human minders as well.