Trump's Trade War Is Making America Love Trade Again. So Why Are Democrats Going Protectionist?

The leading candidates are even more hostile to free trade than Trump.

President Donald Trump's new round of tariffs on Chinese goods is going into effect even as we speak. But the more Trump escalates his trade war, the more unpopular protectionism gets with American voters, especially Democratic ones. So all the Democratic presidential candidates are sprinting to put distance between their trade policies and Trump's America Firstism, right? Wrong!

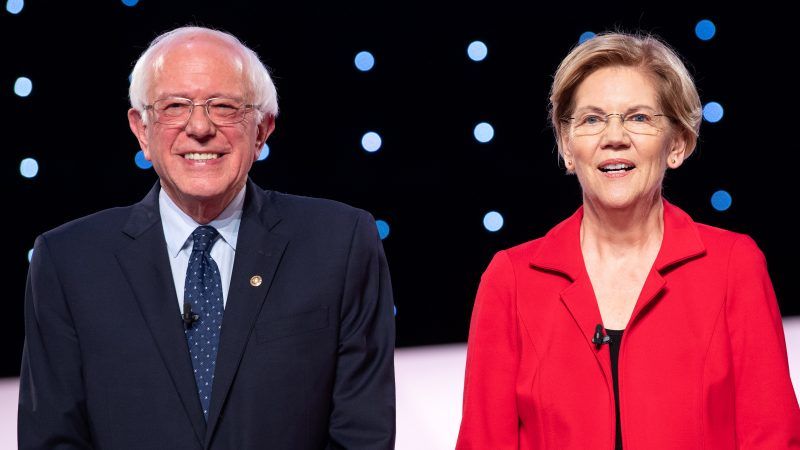

Indeed, the party's leading presidential contenders, Sens. Bernie Sanders (I–Vt.) and Elizabeth Warren (D–Mass.), who are setting the tone for the rest of the pack, are functionally identical to if not worse than Trump on this issue. The reason is that they don't think that average Democratic voters care enough about trade to punish them for their protectionism.

It seems like Trump's trade bashing has done more to bring people around to the cause of free trade in two years than Scottish* political economist Adam Smith's canonical defense in The Wealth of Nations did in nearly 250. Indeed, literally every time the "chosen one" saber-rattles against China, Americans become more positively disposed toward trade. The Chicago Council Survey found last year that support for trade among Americans had touched an all-time high, with 82 percent of respondents saying it was good for the economy, 85 percent saying it was good for consumers like them, and 67 percent saying it was good for America. These findings were pretty much confirmed last month by a Pew Research poll, which found that 65 percent of Americans believe that free trade is good for the country. Two years ago, only 50 percent did.

Democratic voters in particular, Pew found, had jettisoned their 1990s hostility to trade completely. About 73 percent of those who were or leaned Democratic now agree that trade is good for the country, a 13-point jump even from two years ago. Likewise, a Hill-HarrisX poll found that 58 percent of Democrats believe that Trump's China negotiations would result in fewer jobs and economic opportunities.

Even more to the point, in Michigan—a swing state that has historically veered Democratic but Trump narrowly won—a statewide poll by the Detroit Regional Chamber found a few weeks ago that voters believe that tariffs on cars made in foreign countries hurt the state's automotive industry, that tariffs on Chinese imports hurt Michigan farmers, and that tariffs on foreign products hurt consumers like themselves.

Democratic presidential contenders have concluded that all this represents mere revulsion at Trump's style, not a serious change of heart. But Americans would have to be blind to not see the riches that trade has delivered them.

The Peterson Institute for International Economics has estimated that expansion of free trade has generated $2.1 trillion for America between 1950 and 2016. That works out on average to $18,000 in income for American households. These gains have gone disproportionately to working-class households that shop at Walmarts stacked with foreign goods. If an American hasn't felt a bigger pinch from the soaring prices of indigenously generated health care, education, and other services, it is because of the plummeting price of foreign goods.

But last year, for the first time in a decade, the prices of furniture, clothes, and electronics stopped falling. And if Trump does not back off his trade war with China, only divine intervention would stop them from spiking.

Nor are consumers the only ones getting hurt. Producers, the intended beneficiaries of Trump's trade war, are too.

China's retaliatory tariffs on American soybeans, wheat, and pork are decimating farmers. The National Farmers Union has issued a scathing condemnation of Trump's trade war. "[I]nstead of looking to solve existing problems in our agricultural sector, this administration has just created new ones," its statement says. "Between burning bridges with all of our biggest trading partners and undermining our domestic biofuels industry, President Trump is making things worse, not better." Meanwhile, more than 60 percent of imported goods are used in production, so increased tariffs means increased production costs for American manufacturers.

Given all this, Democrats should be mounting a vigorous case against Trump's trade policies, pointing out that beggaring-your-partner trade wars aren't "easy to win"; they are self-injurious.

But that is not what they are doing. They are harrumphing against Trump's Twitter diplomacy and his hyper-belligerent style. But they are otherwise unwilling to stick up for trade or even defend the era of trade liberalization that President Bill Clinton ushered in with the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the normalization of trade ties with China.

Among the top 10 Democrats who will be on the debate stage next week, only former Texas Rep. Beto O'Rourke, who represented the NAFTA-dependent border town of El Paso and is polling at 2 percent, is willing to defend the treaty. Former Vice President Joe Biden, who voted for NAFTA when he was a senator, has gone mum. He slams Trump's "irresponsible tariff war" but then undercuts his own criticism by declaring that "we do need to get tough with China." Sen. Kamala Harris (D–Calif.) tosses offhand comments about Trump's tariffs being a "trade tax" but then quickly abandons the subject. South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg has lambasted Trump's yammerings about America's export imbalance with China as a red herring, but otherwise he is opaque about his plans.

But there is no ambiguity with Sanders and Warren. Sanders has always been an unrepentant protectionist. If he could have his druthers, he would ban trade with any country poorer than America on the Marxist theory that competition with lower-wage workers leads to the immiseration of the American working class.

Warren is even more ideologically ambitious. Like Trump, she couches her plans under the rubric of fair trade. But for Trump, in theory if not practice, that means forcing other countries to slash their trade barriers and moving toward a no-tariff world where no one has an artificial advantage over America. Warren wants to use America's economic might to forcibly enlist countries in a leftist crusade. As The Nation's Todd Tucker approvingly notes, "Warren's trade plan is as much a theory of power as it is a set of ideas."

She has drawn up a tall list of preconditions that countries must meet to qualify to trade with America. These cover almost everything on the leftist wish list, including protecting religious freedom and human rights, signing the Paris Accords, fighting public corruption, combating sex trafficking, stopping tax evasion, and enforcing labor rights. She'd renegotiate every existing trade deal in accordance with her purity criteria. But given that no country on the planet, not even America, currently lives up to her lofty standards, global trade would basically come to a grinding halt under her.

This is totally cuckoo, and it makes Trump look like a veritable trade dove. "Elizabeth Warren's trade policy is even more protectionist and unilateralist than Donald Trump's," writes Daniel Drezner in The Washington Post. Yet if she's the Democratic nominee, he says he'd "hold his nose" and vote for her.

And that, in a nutshell, is why Sanders and Warren have no qualms about indulging their extremist anti-trade fantasies. They believe that moderates are so desperate to get rid of Trump that they will vote for any Democrat. In addition, an extremist strategy will energize their progressive and labor base. A majority of voters in a swing state like Michigan might be put off by their protectionism. But labor unions that Trump managed to woo away with his trade-bashing might return to the Democratic fold if they double down on his mantle.

Time will tell if this strategy will work. But one thing is for certain: If Sanders or Warren win, they will hammer the final nail in the Trump-made coffin of free trade, no matter how much ordinary Americans want the cause to live on.

A version of this column originally appeared in The Week.

Correction: The article originally identified Adam Smith as English instead of Scottish. The error is deeply regretted.