Will Any Democrat Stand Up for Free Trade at This Week's Debates?

A majority of Americans say they favor free trade. But both major parties are moving in the other direction.

President Donald Trump's trade war is slowing investment in America, taxing American farmers and businesses, and, so far, has not produced any of the new trade deals the president promised.

So it's little surprise that Americans are increasingly unhappy with Trump's anti-trade stance. What is surprising, perhaps, is that the Democrats vying to challenge Trump in next year's presidential election seem mostly unwilling to take advantage of one of the incumbent's most obvious weaknesses.

New polling data released Tuesday by the Pew Research Center shows that 56 percent of Americans now say the tariffs are "bad for the country." That's up from 53 percent in September of last year.

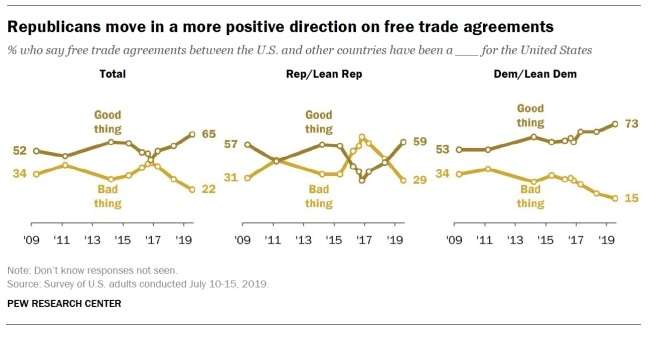

Even more interesting is that the number of Americans who say that signing free trade agreements is a good thing has increased to 65 percent—with majorities of both Democrats (73 percent) and Republicans (59 percent) favoring such deals. Among Democrats, that figure is the highest since Pew started asking about trade in 2009. Republicans' views on free trade, meanwhile, have recovered to pre-2016 levels.

Other recent polls show similar results. A New York Times/Survey Monkey poll released earlier this month showed that 68 percent of respondents—including a majority of Republicans—said Trump's trade policies will raise prices, while 53 percent said Trump's Chinese tariffs will be "bad" for the United States.

Despite clear majorities that oppose Trump's protectionism and favor more trade with more nations, both major parties seem to be moving in the opposite direction. There's little hope that the GOP will rediscover the value of free trade as long as protectionist-in-chief Trump and his coterie of economic nationalists occupy the White House. Which gives the Democrats a clear opportunity to seize the high ground on trade.

Some of the 2020 candidates are tentatively trying to do so. The strongest rebukes of Trump's trade policies, so far, have come from former vice president Joe Biden and from Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Indiana.

"Trump doesn't get the basics," Biden said during a speech in Iowa last month. "He thinks the tariffs are being paid by China. Any beginning econ student at Iowa or Iowa State could tell you the American people are paying his tariffs." Trump thinks he's being tough, Biden added, but that's only because he's forcing American farmers and manufacturers to "feel the pain." Buttigieg has promised to lift Trump's tariffs if elected, calling them a "counterproductive" policy unlikely to change China's behavior while unnecessarily hurting Americans.

Generally speaking, however, the Democrats running for president have criticized Trump's handling of the trade war and his use of tariffs, while tacitly acknowledging that they believe the problem is Trump, and not the policies themselves.

For example, Sen. Kamala Harris (D–Calif.) told CNN's Jake Tapper in May that Trump's habit of "conducting trade policy, economic policy, foreign policy by tweet" was "irresponsible." But when pressed by Tapper she admitted that she largely agreed with Trump's assessment that free trade is a scourge on American workers. This week, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D–Mass.) unveiled a new trade policy paper that similarly criticized the style, but not the substance, of Trump's tariffs. "While I think tariffs are an important tool, they are not by themselves a long-term solution to our failed trade agenda and must be part of a broader strategy that this Administration clearly lacks," Warren wrote, clearly indicating that she would not rule out the use of tariffs if elected.

The subject of trade was raised only once by the moderators at last month's Democratic presidential debates. "We need to crack down on Chinese malfeasance in the trade relationship, but the tariffs and the trade war are the wrong way to go," offered Andrew Yang. "I think the president has been right to push back on China, but has done it in completely the wrong way," said Sen. Michael Bennet (D–Colo.). "Tariffs are taxes," Buttigieg said, before criticizing Trump for being "fixated on the China relationship as if all that mattered was the export balance on dishwashers."

That was basically the extent of the discussion.

Will anything change this week? Partially, that will depend on the questions being asked. The first debate appeared intentionally structured to sideline the incumbent as much as possible, giving the 20-member Democratic field an opportunity to clash with one another, rather than simply teaming-up to attack Trump.

Breaking into the open on an issue like trade will also require some courage from the candidates. Even before Trump came along, Democrats had turned away from the bipartisan consensus that had helped usher in the North American Free Trade Agreement in the 1990s and that stood up to President George W. Bush in the 2000s when he flirted with steel protectionism. By the end of the Barack Obama administration, however, many Democrats (including Warren) were opposing a Democratic administration's attempt to negotiate the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a multilateral trade deal meant as a bulwark against China.

What candidate might be willing to break with the party this week? Despite his previous comments, it probably won't be Biden. As the clear frontrunner in a crowded field, the former Veep has little to gain from putting a target on his back. He is likely to keep playing it safe until after the primaries. Instead, look for a candidate like former congressman Beto O'Rourke to make the pro-trade play. O'Rourke is sinking in the polls and probably seeking a breakout moment—and since trade with Mexico is so critical for the Texas economy, it would make sense for the Texas candidate to embrace the issue.

If they are not going to follow the polls, the Democratic candidates should at least be willing to follow the economic data showing that voters are right to favor trade agreements. A 2017 analysis by the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a trade policy think tank, shows that international trade boosted American household incomes by about $18,000 per household since 1950—and that the gains flowed disproportionately to lower-income households. The Commerce Department says that more than 11 million American jobs are directly related to foreign investment or the export of American goods. And the mere existence of NAFTA boosts the U.S. economy by about 0.5 percent per year. There is no doubt that the past half-century of increasingly freer trade has made America better off.

Polls show that a majority of voters recognize the many benefits of trade. But in a campaign in which Democrats seem determined to outdo one another with offers of "free" healthcare and "free" college tuition, free trade may get ignored.