Trump Says in State of the Union He Wants to Wipe Out AIDS. Should We Be Skeptical?

Ending the spread of HIV is within our reach, but the administration's approach to opioid abuse is a problem.

In his State of the Union address Tuesday evening, President Donald Trump declared a goal to completely stop the transmission of HIV in America by 2030. From his speech:

In recent years we have made remarkable progress in the fight against HIV and AIDS. Scientific breakthroughs have brought a once-distant dream within reach. My budget will ask Democrats and Republicans to make the needed commitment to eliminate the HIV epidemic in the United States within 10 years. We have made incredible strides, incredible. Together, we will defeat AIDS in America and beyond.

The idea of eliminating HIV transmission may sound completely absurd, like President Barack Obama promising a program in his final State of the Union Address in 2016 that then-Vice President Joe Biden would oversee a cure cancer.

But stopping the transmission of HIV in America is potentially achievable on the basis of the medical innovations we've achieved in this decades-long fight against HIV and AIDS. Medical therapies have dramatically extended the lives of people diagnosed with HIV; new treatments that have been widely distributed just this decade are able to suppress the virus in people's bodies to the degree that HIV-positive people cannot spread the virus to others.

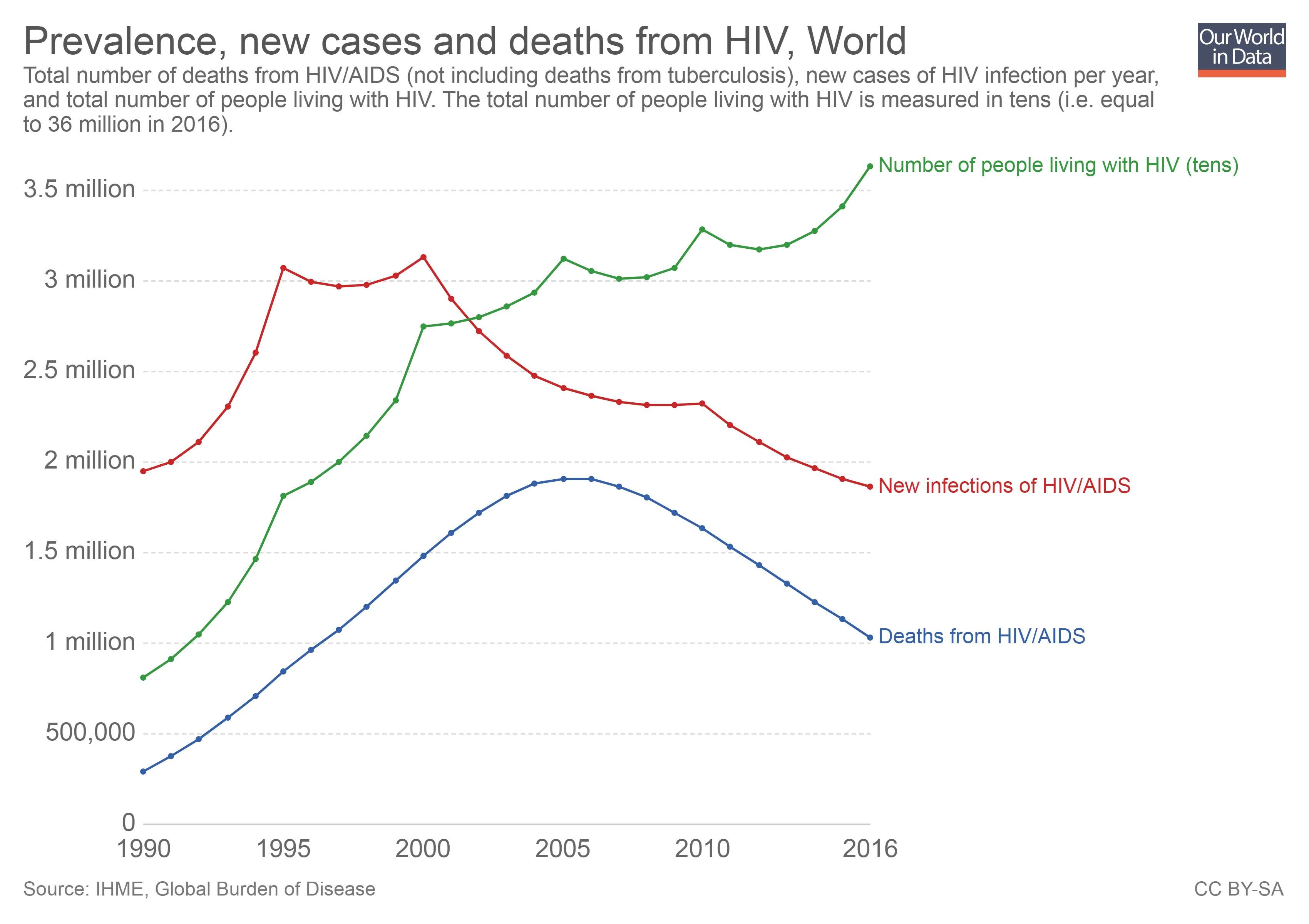

Here's what the curve of HIV infections and deaths looks like around the world these days, courtesy of Our World in Data:

Not only are fewer people dying, fewer people are getting infected. In America, that's partly attributable to suppression treatment. According to newly updated data from the Kaiser Family Foundation, half of people in the U.S. with HIV are virally suppressed, meaning the virus levels in their body are undetectable. They are not cured, but they cannot spread HIV to negative partners. Similarly, drugs like Truvada (a pre-exposure prophylactic, or PrEP), when taken by HIV-negative people in high-risk categories, keeps them from becoming infected when exposed through sexual activity.

Since only half of HIV people are virally suppressed, there's still a significant number of new infections in the United States—the most recent data shows 38,500 new HIV cases in 2015. And according to Kaiser, 14 percent of people infected with HIV do not know they have the disease. And 6,000 people died of HIV- and AIDS-related illnesses in 2016 in the U.S. alone.

So that's a lot of work, and folks are skeptical that the Trump administration is going to actually do much, given that they've previously attempted to cut domestic spending on HIV care. This shouldn't necessarily be a warning sign—success at stopping the spread of HIV should at some point result in less federal spending—but this isn't an administration that has shown an interest in spending less money.

Another warning sign is that the administration talks about reducing HIV transmission reduction while clinging to a prohibitionist approach to reducing opioid abuse. Trump and the Department of Justice have taken a punitive approach to the opioid crisis, blaming drug lords, going after doctors, and punishing patients for needing pain treatment, ultimately sending people to the street to get opioids of unknown origin, often contiminated with illicit fentanyl. Jacob Sullum has noted that while opioid prescriptions have fallen, opioid overdose deaths have increased. Taking a harsh approach toward those who are seeking pain prescriptions is not helping at all.

This counterproductive reaction to the opioid crisis is especially relevant to any effort to fight HIV because of the risk of infection from shared needles. In a December speech at a national conference on HIV care and treatment, Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar noted that the opioid crisis had direct impact on their efforts to fight HIV:

One increasing challenge since the last HIV strategy is the growth of our country's opioid crisis.

The crisis has made injection drug use more common and helped to spread infectious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis.

Combating the opioid crisis has been one of this administration's highest priorities.

Azar's own Twitter feed brags about the number of people the administration has charged for distributing illegal opioids and the 22 percent drop in the number of opioids prescribed, but he does not mention that overdose deaths nevertheless continue to rise.

If the Trump administration is actually serious about ending the spread of HIV, it needs to recognize that sending opioid users into the black markets for painkillers is no way to stop a health crisis, whether we're talking about overdoses or the spread of viruses.