Debate: Intellectual Property Must Be Protected

Should the law respect copyrights and patents?

AFFIRMATIVE:

I.P. Holders Need the Legal System To Uphold Their Rights

James V. DeLong

If any gathering of people of libertarian bent becomes dull, raise the topic "intellectual property." The result will be an entertaining escalation in both outrage and decibels. The only certainty is that no minds will be changed, because the pros and the cons emphasize different values and the twain show no signs of meeting.

The case for recognizing a creator's right to his creations and his claim on the state to help protect this right rest on the same foundations as the arguments for protecting tangible property: Lockean entitlement to the fruits of one's labors; economic considerations of the importance of incentives and mechanisms for investment (and of the freedom of anyone with an entrepreneurial idea to bet on it without approval by hierarchies); the political benefits of separating people's livelihood from power structures (the old idea of the independent yeoman class, as modified for a society in which land has become less important as a factor of production and ideas more so); and the philosophical concepts of human agency and personal dignity, combined with the role of property—intangible as well as tangible—in making them a reality rather than an abstraction.

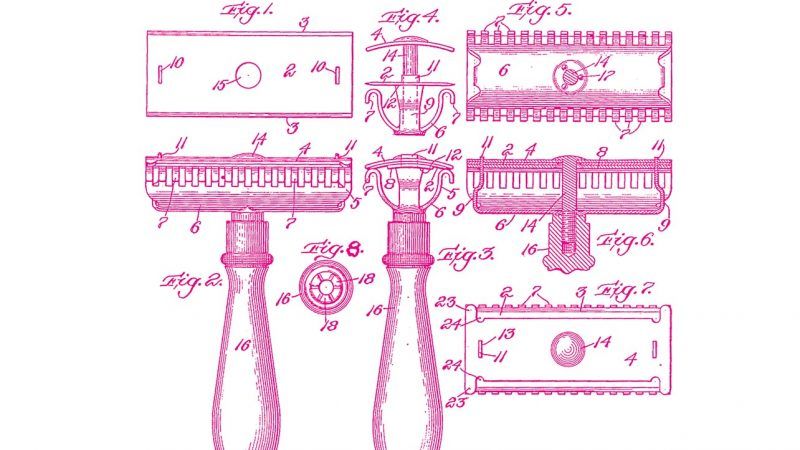

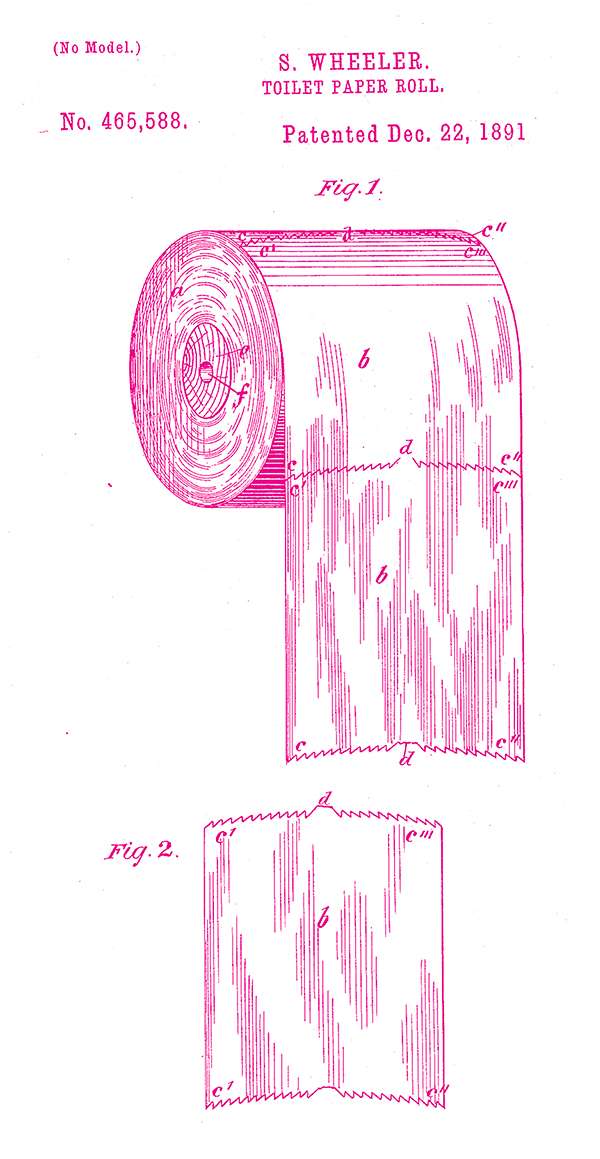

As always, it's in moving from the abstractions to the realities where the devilment lies. Defining and bounding intellectual property rights is complicated. The field is subdivided into four major domains: Copyright governs written, visual, and audio creations; patents apply to inventions; trademarks deal with brand protection; and trade secrets cover confidential information. Each has special characteristics and is subject to its own special rules.

Other than trade secrets, these domains differ from tangible property in a crucial way. Because tangible property can be locked up, nailed down, or fenced in, anyone who wants to infringe my rights must make physical contact with it. That makes self-protection the first line of defense, with invocation of state power as a backup. (Because trade secrets are much like tangible property in this respect, they tend not to rouse as much resistance.)

Intangible property, in contrast—to be either useful or lucrative—must be made available publicly and can be easily copied. Sometimes self-protection is possible by integrating tangible property with the intellectual product. Newspaper content, for example, was for decades protected by the expense of printing and distribution. But usually the holders of intellectual property must rely upon the legal system to uphold their rights.

It is not surprising that this intimate intertwinement of property with state power worries libertarians, as indeed it should. A government-enforced monopoly based on a patent or copyright looks a lot like a monopoly granted by a self-seeking officeholder to his political favorite. The founders of the American republic had experience with such preferential favoritism—the Boston Tea Party was more about the East India Company's monopoly than the taxes being levied—and the U.S. Constitution gives Congress the power to hand exclusive rights only to authors and inventors for limited periods of time. It also specifies that the purpose is "to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts." No monopolies were to be granted for importing caffeinated beverages.

On the whole, though, the system has done a reasonable job of policing the boundary. Patents are granted only for inventions that meet the criteria laid out in the first known patent law, from Venice in 1474: novelty, creativity, usefulness, non-obviousness, and a working model. Copyright is also hedged with limitations; only specific expression, not general ideas or plotlines, can be protected. Both patent and copyright are subject to rich and complicated bodies of legal doctrine, which testifies to their importance.

Things do indeed go awry sometimes, especially in times of rapid change. In the late 19th century, rural America was outraged by the "driven well patent," which covered a pipe pounded into the ground. A decade or so ago, patents were granted too freely for computerization of familiar practices, such as conducting a Dutch auction. But the system, for the most part, works.

Copyright is a bigger problem. To a large degree, the anti-I.P. forces have gotten their wish. The internet, and especially Google search and YouTube, have made people's rights to their own creations practically unenforceable for anyone who isn't a large corporation with a battalion of lawyers on call.

The results are mixed—at best. For those who use information as a tool for some other purpose, and whose business model does not depend on selling that information, the web has produced spectacular results. Commerce is now easier, and think tanks and other groups benefit enormously from the increased reach they can attain.

But for those of us who are dependent on monetizing information itself, the results have been disastrous. News organizations have been reduced to living off of the mere crumbs that fall from the maw of Google's advertising algorithms. In many ways, the traditional news business no longer exists at all. Instead, the product is the consumer, whose eyeballs can be sold and, because tailored ads are more effective and thus more lucrative, whose privacy is increasingly invaded.

In the entertainment field, individual artists have always had a hard time making a buck, but the trend, as intellectual property rights become less reliable, is toward ever-greater industrial concentration. A creator must sign on with one of the new barons, such as Amazon or Netflix, to access the necessary clout and resources to protect herself.

Sure, some artists do well in this system, but most cannot, and anyone outside the magic circle is fish bait. One of the great promises of the internet was that people on the fringes could use it to access a wider array of potential customers and become less dependent on intermediaries. Without defensible property rights, this is a pipe dream.

Time will tell how this all works out, but the current state of the news business is hardly a cause for libertarian exultation. Personally, for both news and entertainment, I mourn a lost alternative world in which strong intellectual property protections and micropayments together could have restored both consumers and producers to their proper, and more prosperous, roles.

NEGATIVE:

Patents and Copyrights Are Dubious Legal Instruments

Tom G. Palmer

Patents and copyright are frequently in the news, with headlines such as "Amazon Patents Aerial Fulfilment Centers for Improved Drone Delivery" and "Elon Musk, Artist Settle Copyright Row Over Unicorn." Sometimes the conversation turns to the alleged need for legislative changes to lengthen or strengthen patent and copyright protections. The arguments in favor of such moves are propelled by moral claims about fairness and just reward but also by dubious claims about increased innovation and economic growth. (Trademark and trade secret protections are generally defended for other reasons based on contracts.)

Generally, both the very best defenses and the very best critiques of patents and copyrights were crafted by people working in the libertarian tradition. The reason isn't hard to identify: Patents and copyrights have come to be called "intellectual property," and libertarians see property and liberty as intimately connected. John Locke argued that people join in society "for the mutual preservation of their lives, liberties and estates, which I call by the general name, property."

Property is associated with prosperity, voluntary cooperation, and social harmony. It overcomes many "free rider" problems by creating incentives for people to take care of what is their own: In the fourth century BCE, Aristotle pointed out that "that which is common to the greatest number has the least care bestowed upon it."

Yet as Fritz Machlup and Edith Penrose pointed out in their classic study "The Patent Controversy in the Nineteenth Century," "those who started using the word property in connection with inventions had a very definite purpose in mind: they wanted to substitute a word with a respectable connotation, 'property,' for a word that had an unpleasant ring, 'privilege.'" Patents and copyrights are privileges granted by political authorities. They were originally used to advance the interests of the rulers, not of the ruled; monopoly rights were often sold or handed out for political reasons. Only later were these instruments reformulated as attempts to create an artificial scarcity that would generate incentives for authors and inventors.

If I write a song and you sing it, you may be infringing a copyright granted to me by the state, and a court may be authorized to enjoin you from using your voice as you choose—meaning that your liberty of action over your body is lessened by my legal privilege. The problems with patents are no less severe, especially when you consider that merely filing a patent application 10 minutes earlier confers a full monopoly over the invention, regardless of the claims another inventor may have.

Merely calling a privilege "property" doesn't mean that it has the characteristics of property that libertarians find desirable. Occupational licenses, monopolies, farm subsidies, and other privileges are sometimes referred to as property (and in many cases have characteristics of property—they're transferrable, can be borrowed against, etc.), but that is no reason to extend to such privileges the traditional libertarian respect for the "lives, liberties, and estates" that were designated by Locke as property.

Thomas Jefferson, after some years as a member of the federal Patent Board, wrote that "if nature has made any one thing less susceptible than all others of exclusive property, it is the action of the thinking power called an idea, which an individual may exclusively possess as long as he keeps it to himself; but the moment it is divulged, it forces itself into the possession of every one, and the receiver cannot dispossess himself of it. Its peculiar character, too, is that no one possesses the less, because every other possesses the whole of it. He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me." Jefferson granted that the state may award such monopolies "as an encouragement to pursue ideas which may produce utility," but he was skeptical that they actually served that function. That skepticism has been borne out by historical experience.

Plenty of innovation takes place in fields without patent protection, including effectively the whole U.S. aviation industry from 1917 to 1975. Most firms patent to avoid having competitors register patents before them, or use the number of patents filed to measure the productivity of their R&D departments. There is no compelling evidence from empirical research that patents generate overall economic benefits, with one possible—and significant—exception: chemical compounds.

In many cases, these compounds can be easily reverse-engineered and are also relatively easy to define. In the pharmaceutical industry, the costs of R&D and of evaluation by the Food and Drug Administration can be astronomical, and the consumer benefits can be very substantial. Pharmaceuticals may be the best case (and I write "may," since there could still be other solutions in that instance) that general benefits can flow from grants of monopoly privileges—so long as the formulae are published, ensuring that generics can be made available after the patents expire, and the duration of the monopoly is limited. But one exception does not a general case make.

The power to hand out such legislative monopolies is expressly limited by the Constitution, but those limitations are under attack in ways that clearly have nothing to do with promoting the further "Progress of Science and useful Arts."

Extending the copyright of a film won't cause more of that film to be produced. The current patent system, rather than speeding up innovation, may even be hampering it, as patents are issued with barely any examination of whether the application is overly broad or whether someone else is already producing what the patent covers. "Patent mill" law firms then buy up such patents and shake down tech firms by threatening patent infringement suits that would, even if unsuccessful, cost the targets millions to defend against. The tech companies often agree to hefty settlements (accompanied by nondisclosure agreements) with the law firms because doing so is less costly than litigation would be. In discussions with CEOs of electronics firms manufacturing in the U.S., I've been told that the existing system increases the cost of doing business and that, despite their cutting-edge position, they'd prefer to be rid of the whole mess.

The future of civilization does not hinge on whether we extend, diminish, or abolish copyright and patent protections. There are other, more critical issues before us. But people who value liberty should be skeptical of moves to lengthen or strengthen legislatively granted monopoly privileges. Putting the lipstick of "property" on a pig shouldn't make it sexy.