The Days of Paying More to Live Near the Metro Are Coming to an End

Fewer people are willing to pay a premium to live near a subway stop as public transportation stumbles and ride-sharing offers better options.

Until recently, the best way to get around many big cities was to use public transportation. Homes with easy access to subway systems therefore commanded a premium. Consumers were willing to pay more to avoid having to drive and pay for parking, or to walk a long distance to the metro in bad weather.

That's starting to change, according to a new report from MetLife. Uber, Lyft, and other ride-sharing options are reshaping cities, giving people greater flexibility in where they live and how they commute. Combine that with the struggles of several major mass transit systems, and that means there's less reason to pay a few hundred dollars extra every month to be close to the subway.

"Advances in transportation have shaped the form, pace, and direction of real estate demand throughout the nation's history," Metlife's analysts conclude. "We believe that the advent of ridesharing services and the widespread adoption of autonomous, electric vehicles will do so once again."

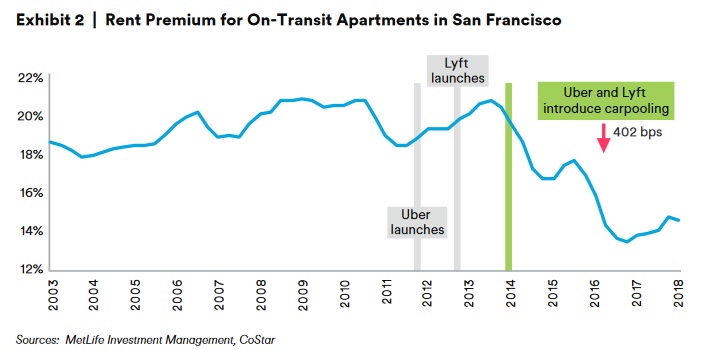

In San Francisco, for example, the MetLife report finds that properties near metro stations typically fetched a 20 percent premium over similar properties in other locations. That premium has been on the decline since Uber and Lyft started operating in the city. (Uber launched in 2010, Lyft in 2012). It now averages about 15 percent.

As with taxi companies that invested in expensive medallions that were worth more because cities limited their supply, some people will see a downside from the evaporation of an artificial bonus on certain properties. Those who own homes and condos along metro lines in major cities might learn they paid extra for an geographic advantage that won't exist when they try to sell their real estate later.

But this is mostly a positive development. It will allow more people to live where they want. It could also change the calculus for developers, encouraging them to build more homes outside of rigid public transportation corridors.

"One of the first major impacts," the MetLife report suggests, "will be the increased value of development sites with good access to uncongested roadways, but limited access to public transportation."

More options for getting around should be welcomed, particularly when so many public transit systems are beset by mismanagement, cost overruns, maintenance problems, and general operational shittiness. More people relying on ride-sharing services could add to congestion on city streets, of course, but there are solutions to that problem—like conjestion pricing and other fee structures—that distribute those costs efficiently.

By reducing the premiums required to live near a burning subway line, Uber and company aren't just changing how we move around a city. They're giving us more power to choose where we live, too.