Rising Tax Rate Can't End Illinois' Economic Drought

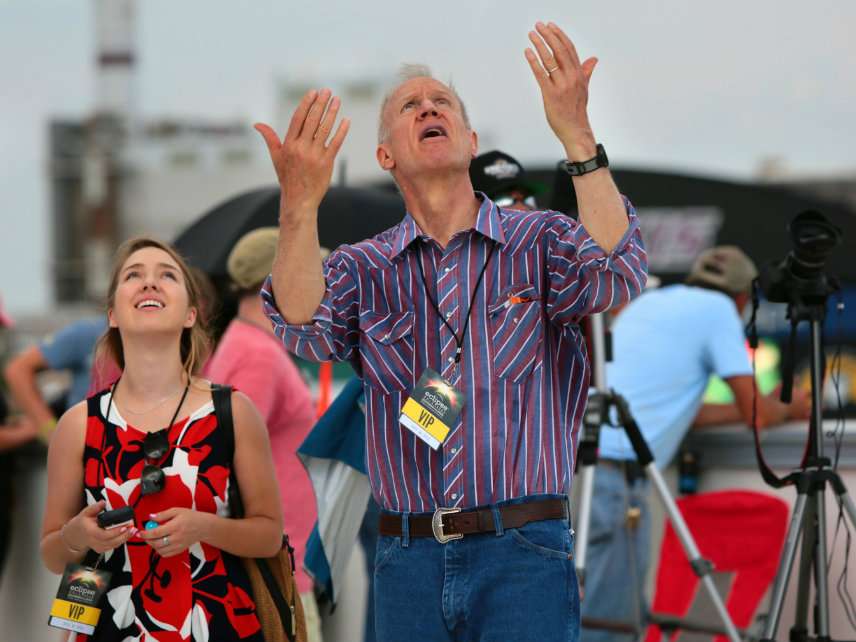

Yet leading candidates to replace Gov. Bruce Rauner think the only problem with the state's income tax rate is that it doesn't go high enough.

Illinois has made many contributions to America, but lately its biggest service is making other states feel better about themselves. With the biggest public pension obligations, the slowest personal income growth, and the biggest population loss of any state, it has consistently recorded achievements that are envied by none but educational to all.

The state is in the midst of a debilitating fiscal and economic crisis. Because necessity is the mother of invention, crises can be restorative, forcing creative solutions.

Against a starkly unsuccessful incumbent Republican governor running in an unhospitable national environment, Illinois Democrats have the chance to win and, with control of the General Assembly, to devise serious solutions to intractable problems. But the Democratic race for governor has been notable mainly for the bad ideas it has elicited.

Illinois has endured two income tax increases in the past seven years. In 2011, the flat rate on individual income jumped from 3 percent to 5 percent. In 2015, under the original terms, it fell to 3.75 percent—a "cut" that left the rate 25 percent above what it was in 2010. Then last year, over Gov. Bruce Rauner's veto, the legislature raised the rate to 4.95 percent.

None of these changes has ended the state's economic drought, and it's reasonable to assume they actually made it drier. But the leading candidates to replace Rauner think the only problem with the income tax rate is that it doesn't go high enough.

Billionaire philanthropist J.B. Pritzker, businessman Chris Kennedy (son of Robert F. Kennedy) and state Sen. Daniel Biss have all endorsed a graduated levy, which would require removing the state constitution's requirement that any income tax "shall be at a non-graduated rate." The change would allow tax increases to be targeted on high-income taxpayers as they can be at the federal level.

But well-paid people can't generally leave the country to find lower tax rates. They can leave one state for another, and they do.

Amending the state constitution would allow the top rate to go much higher. The maximum rate in California is 13.3 percent. Illinois already ranks ninth-highest in the country in total state and local tax burden.

Income tax rates are not the sole determinant of economic fortunes, but everything else being equal, the higher they go the likelier they are to impede growth. It's probably not a coincidence that of the five states with the highest rate of job growth since the Great Recession, two have no income tax.

Illinois is not likely to change that pattern. A 2016 poll by the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute at Southern Illinois University found that nearly half of residents would like to leave the state—and that "taxes are the single biggest reason people want to leave."

Illinoisans don't think the services they get justify the price they have to pay. With a graduated income tax, the number of people heading for the exits would probably rise.

That might be a good thing, because under a proposal advanced by Pritzker and Biss, it would get harder to find a place to live. They want to repeal the state ban on municipal rent control, on the obvious ground that, as one candidate for mayor of New York famously said, "the rent is too damn high."

What Illinoisans might note is the irony of that complaint's being made in the city that pioneered rent control and maintains it today. In fact, New York and San Francisco have the highest average rental rates in the country despite—or rather, because of—a long history of restricting them.

The only reliable long-term cure for high housing costs is increasing the supply of dwelling spaces. Rent control works to curtail the supply of rental housing by making it harder for landlords to profit, thus encouraging them to convert existing units into condominiums while discouraging new building.

In San Francisco, the median rent is triple the prevailing rate in Houston, which has no rent control. New York City rents are about double those in Chicago. The onerous cost of housing in rent-controlled cities is what is known in medicine as an iatrogenic condition: one caused by treatment.

Illinoisans were disappointed after electing a new governor four years ago in the hope he would restore fiscal health, functional government and economic progress. They may avoid disappointment this time only because they know better than to hope.

COPYRIGHT 2018 CREATORS.COM