Who Are the European Jihadists?

Young and alienated, they tend to be uninterested in theology and not closely connected with the larger Muslim community.

Last week the political scientist Olivier Roy delivered a fascinating talk at a conference sponsored by the German counterpart to the FBI. Drawing on data about Europeans who join jihadist groups, Roy argues that they're primarily driven not by theology, nor by deprived backgrounds, but by a particular sort of youthful alienation.

Roy concludes that we can't make broad psychological generalizations about this subculture, beyond the unsurprising fact that they're frustrated and resentful. They come from a wide range of sociological backgrounds, but the majority are "second generation Muslims born in Europe, [and] the others are converts; almost none came as a young adult or as a teenager to Europe from the Middle East." Many of them "have a past of petty delinquency and drug dealing" followed by "a sudden and rapid 'return' to religion (or conversion), immediately followed by political radicalisation. There is a clear 'breaking point,' often linked with a personal crisis (jail for instance)."

These jihadists are

clearly a youth movement: almost all of them [were] radicalised to the dismay of their parents and relatives (a huge difference if we compare with Palestinian radicals). Most parents not only disapprove of their children's radicalisation, but actively try to bring them back or even to have them arrested by the police. This pattern is found as well among parents of converts (a fact we can expect), but also among Muslim parents (Abaaoud in Belgium). In this sense the radicals do not express an anger shared by their milieus or by the Muslim "community."

It is a peer phenomenon: they radicalise in the framework of a small network of friends, whatever the concrete circumstances of their meeting may be (neighbourhood, jail, internet, or sports clubs). This puts them often at odds with the traditional view of family and women in Islam. These groups are often mixed in gender terms, and the women play often a far more important role than they themselves claim (Boumediene in the Charlie Hebdo killers' team). They intermarry between themselves, without the parents' consent. In this sense they are closer to the ultra-left groups of the 1970s.

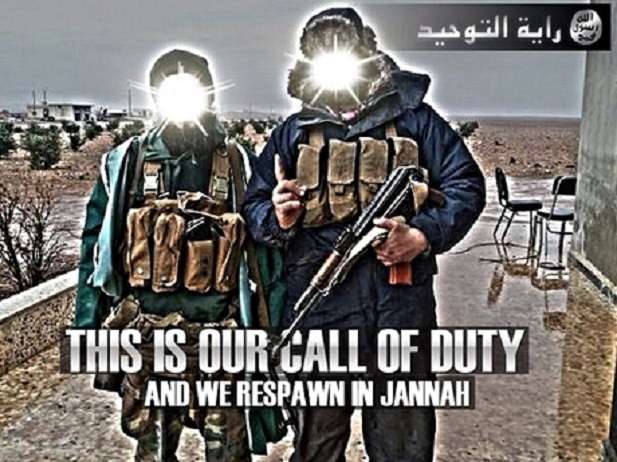

Roy argues that the chief motive for young men joining a jihad is a "fascination for a narrative," a storyline starrring a "small brotherhood of super-heroes who avenge the Muslim Ummah." That Ummah "is global and abstract, never identified with a national cause," and the narrative draws not just on Islam but on pop-culture products such as video games.

Roy has some particularly interesting comments on the religious dimension of the jihadists' worldview:

The revolt is expressed in religious terms for two reasons:

- Most of the radicals have a Muslim background, which makes them open to a process of re-islamisation (almost none of them being pious before entering the process of radicalisation).

- Jihad is the only cause on the global market. If you kill in silence, it will be reported by the local newspaper; if you kill yelling "Allahuakbar," you are sure to make the national headlines. The ultraleft or radical ecology is too "bourgeois" and intellectual for them.

When they join jihad, they adopt the Salafi version of Islam, because Salafism is both simple to understand (don'ts and dos) and rigid, providing a personal psychological structuring effect. Moreover, Salafism is the negation of cultural Islam, that is the Islam of their parents and of their roots. Instead of providing them with roots, Salafism glorifies their own deculturation and makes them feel better "Muslims" than their parents. Salafism is the religion by definition of a disenfranchised youngster.

Incidentally, we should make a distinction between religious radicalisation and jihadist radicalisation. There is of course an overlap, but the bulk of the Salafists are not jihadist, and many jihadists don't give a damn about theology.

Only a few of the militants whose lives Roy reviewed attended a local mosque regularly, and in general they had only a loose connection—or no connection—to Europe's larger Muslim communities. "This," Roy writes, "explains why 1) the close monitoring of mosques brings little information; 2) Imams have little or no influence on the process of radicalisation; 3) 'reforming Islam' does not make sense: they just don't care about 'what Islam really means.'" And so, he concludes,

To promote a "moderate Islam" to bring radicals back to the mainstream is nonsense. They just reject moderation as such.

To ask the "Muslim community" to bring radicals back to normal life is also nonsense. Radicals just don't care about people they consider as "traitors," "apostates," or "collaborators" as long as they don't choose the same path.

To consider Islam only through the lenses of "fighting terrorism" will validate the narrative of persecution and revenge that feeds the process of radicalisation.

To read the whole thing, go here. For a broader look at the way people talk about "radicalization"—a term that covers a lot more than the group Roy is discussing—go here.