Sara Mayeux on the Dark Side of Police Reform

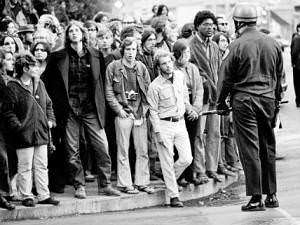

The costs and benefits of modern American policing have not been distributed evenly.

If you owned a gay bar in 1950s San Francisco, there were ways of protecting your patrons from harassment, thereby maintaining a clientele, but it would cost you. An old-time bartender recalls the lieutenant who came in one morning and explained that he needed $500 a month for—supposedly—the Police Athletic League: "The captain'll be by to collect it next Tuesday at 7:30."

But San Francisco was changing. In the late 1950s, a group of gay bar owners made the shrewd calculation that San Francisco's up-and-coming leaders cared about corruption more than they worried about homosexuality, and they confronted the police chief, who quickly recognized the public relations value of a high-profile crackdown on graft. The so-called "gayola" scandals culminated in 1960 with the month-long criminal trial of two sergeants and two patrolmen accused of demanding payoffs. Jurors acquitted all four officers, but the fact of the trial itself sent a strong message. By 1966, the San Francisco police chief had ended organized raids on gay bars and even established a gay community liaison within the police department.

A happy ending? Not exactly. In a review of Christopher Lowen Agee's new book (The Streets of San Francisco: Policing and the Creation of a Cosmopolitan Liberal Politics, 1950-1972), Sara Mayeux notes that this was not a triumph of modern, cosmopolitan governance over bribes and billy clubs. Because the story does not end there: The officers implicated in the gayola trial were transferred to Potrero Station, where they enjoyed free rein to administer beatdowns, or worse, to residents who were young, black, and poor.

The story encapsulates the dark side of mid-century police reform in America. The traditional regime of decentralized, discretionary, corrupt policing was replaced with the top-down, bureaucratic, and ostensibly more regulated urban police departments that we know today. As a result city dwellers feel free to socialize in whatever bars or gender combinations they please. But the costs and benefits of modern American policing have not been distributed evenly.