Jerry Brown's Legacy Depends on Focus He Doesn't Have Yet

Will he emphasize fiscal control or far-reaching environmental agenda?

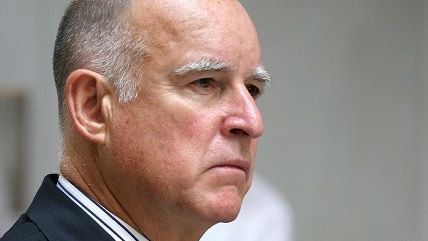

As he entered the Assembly chambers to give his final inaugural address on Monday, Gov. Jerry Brown — elected to an unprecedented fourth term in November — was greeted by boisterous applause from legislators and audience members. There's little question Brown heads into his final term with a storehouse of goodwill and political capital.

Pundits who have debated how Brown will spend that capital had their questions answered. He will take two approaches — one somewhat conservative and the other more radical. The governor says he will keep the lid on government spending and long-term fiscal liabilities, while pursuing an ambitious climate-change agenda designed to slash the state's "carbon pollution" footprint and prod the rest of the world into following suit.

Given the strong Democratic tilt of the state's politics, the more conservative fiscal ideas were not as heartily received inside the chambers as the progressive part of his agenda. "My plan has been to take them on one at a time," he said, referring to California's unfunded pension and other liabilities. "For the next effort, I intend to ask our state employees to help start pre-funding our retiree health obligations, which are rising rapidly."

Climate change, fiscal future top Brown's agenda

Brown didn't ask for more state funds, but instead called on state employees to pitch in to fill the void, which evoked tepid applause. That's a potentially significant statement. "He's pressing the boundaries of what Democrats can do," said Dan Pellessier, president of California Pension Reform. "I'm hopeful the governor will now be liberated to address the unsustainable costs of retirement promises."

Pellessier touches on the big questions: Will a lame-duck Brown finally take on public-sector unions and propose deep and difficult reforms to deal with those unsustainable promises? Or will he place his real time and energy into expanding the state's environmental regulations? The answers will determine his legacy.

"I believe I know Jerry well and that he worries about and works toward a legacy more than almost any other politician," said Art Laffer, the Reagan-administration economist and father of supply side economics. "Like the sly old crocodile on the banks of the Zambesi River, he's waiting for his chance to move." Laffer expects a fiscal "game changer."

Brown certainly is pushing a game changer on the environmental front. Referring to the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, he proposed these objectives for the next 15 years: increasing the proportion of the state's renewable energy use to 50 percent from round 30 percent, slashing car and truck petroleum use in half, and doubling the efficiency of the state's buildings. This is "a very tall order," Brown admitted.

It's an expensive one, too. The governor will be in Fresno on Tuesday to break ground for the $68-billion high-speed-rail line designed to help combat climate change. The only thing that will break, said Assemblyman Jim Patterson R-Fresno, is the bank. Brown may be holding the line on general-fund spending, but his conservative critics say his rail and Delta plans will ratchet up long-term debt spending.

It's not clear how Brown will square that circle, although contradiction is nothing new for him.

In 1978 voters had approved Proposition 13, which put a cap on property taxes. The governor was a foe of the initiative, but so earnestly implemented it that he eventually won the praise of the proposition's co-author, Howard Jarvis. In his second inaugural in January 1979, Brown praised the tax revolt as a legitimate reaction by an angry citizenry, and warned against "false prophets" who "advocate more and more government spending as the cure."

So it's not surprising that Brown has focused part of his agenda on reining in government's long-term debts, just as it's not surprising that Brown still sees environmental peril — "the growing assault on the very systems of nature on which human beings and other forms of life depend," as he put it in his Monday speech — as a core part of his mission. He has long been comfortable advancing both themes.

During his speech, Brown said the issues his father Pat Brown raised during his inaugural 56 years ago "bear eerie resemblance to those we still grapple with today." The general themes of politics — taxes, the size of government, crime and infrastructure — share similarities going back to ancient times. But this is a different California today than it was during Brown's first term.

Whereas voters in the 1970s voted to slash their taxes, voters in 2012 raised them. In Brown's early terms, crime (and the fear of it) was soaring and his anti-death-penalty Supreme Court appointees ultimately became touchstones in an angry recall campaign centered on the crime issue.

With violent crime at near-historic lows these days, Brown touted "less expensive, more compassionate and more effective ways to deal with crime" — an issue that has increasingly gained traction across the political spectrum.

"He has held the line against more ambitious spending from the Democrats in the Legislature, which allows him to balance a rightward lean on budget matters with a more liberal approach to environmental and public safety issues," said Dan Schnur, a University of Southern California professor and former Republican political consultant.

This is classic Jerry Brown and his overly discussed "Canoe Theory of Politics" (paddle a little to the left, and then a little to the right). Brown is a man who wants to "forge a bold new future grounded in the past" but who won't drive the state "off a cliff," added his wife, Anne Gust Brown, while introducing him to the Assembly.

That's no doubt true. But if he puts the aggressive environmental goals above the more-conservative fiscal ones, he could drive the state a little too close to the precipice.\