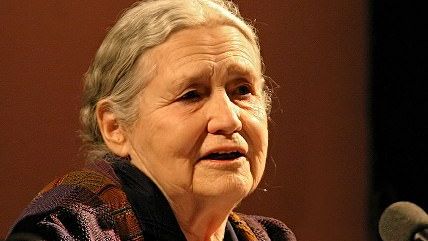

Doris Lessing's Impatience With Political Correctness

As we bid Lessing farewell, the blight she spoke of-"political correctness" and, in particular, its toxic feminist strain-is on the move again.

The tributes to Doris Lessing, the novelist and Nobel Prize laureate who died on November 17 at 94, have given scant attention to one aspect of her remarkable career: this daughter of the left, an ex-communist and onetime feminist icon, emerged as a harsh critic of left-wing cultural ideology and of feminism in its current incarnation.

Over 20 years ago, I heard Lessing speak at a conference on intellectuals and social change in Eastern Europe at New Jersey's Rutgers University. It was 1992, the dust still settling from the collapse of the Soviet empire. Lessing opened her memorable talk with a warning: "While we have seen the apparent death of Communism, ways of thinking that were born under Communism or strengthened by Communism still govern our lives." She was not talking about the East but the West, where coercive "social justice" had reinvented itself as "antiracism," feminism, and so forth. "Political correctness" had become, Lessing said, "a kind of mildew blighting the whole world," particularly academic and intellectual circles—a "self-perpetuating machine for dulling thought."

Those remarks (published in abridged form in the New York Times Book Review) have lost none of their relevance. Unlike some critics on the right, Lessing readily acknowledged that encouraging people to "re-examine attitudes" toward gender, race, and other areas of traditional prejudice was a good thing. Unfortunately, "for every woman or man who is quietly and sensibly using the idea to look carefully at our assumptions, there are twenty rabble-rousers whose real motive is a desire for power."

In a later interview with Salon.com, Lessing elaborated on the traits that made "political correctness" an heir to pro-Communist "progressive thinking": "a need to oversimplify [and] control," intolerance toward disagreement, and "an absolute conviction of your own moral superiority."

On other occasions, she directed her critique more specifically at feminism. It was a natural subject for Lessing, whose 1962 novel, The Golden Notebook, was hailed as a landmark work about the lives of women navigating the uncertain terrain of their new freedoms. (It is a measure of that era's very real sexism that even admiring reviews were often laced with condescension: in The New Republic, Irving Howe compared Lessing only to other female authors and commended her for eschewing "those displays of virtuoso bitchiness which are the blood and joy of certain American lady writers.")

Lessing always resisted attempts to conscript her into the sisterhood—and not just, as some suggest, because she rebelled against all labels and pressures but because of fundamental disagreement with feminism's direction.

In 2001, speaking at the Edinburgh Book festival, Lessing caused shock waves with a blistering indictment of the "rubbishing of men which is now so part of our culture that it is hardly even noticed," including boy-bashing in schools. (She recounted sitting in on a class in which the teacher blamed all wars on male violence while "the little boys sat there crumpled, apologising for their existence.") Pulling no punches, Lessing declared, "The most stupid, ill-educated and nasty woman can rubbish the nicest, kindest and most intelligent man and no one protests. Men seem to be so cowed that they can't fight back, and it is time they did."

This was no isolated outburst. In a New York Times Magazine interview seven years later, Lessing was even more scathing: the feminist movement, she said, had produced some "monstrous women" by encouraging women to be "critical and unpleasant" at men's expense.

Yet Lessing never rejected the ideals of equality and liberation. Her final novel, Alfred and Emily (2008), reimagined the life of her difficult mother in an alternate world where she got the chance to be a pioneering educator rather than a frustrated housewife. In her remarks at the Edinburgh festival, she stressed that "great things have been achieved through feminism," including the rise of "many wonderful, clever, powerful women"—much as she deplored the male-bashing that came with those gains. Far from re-embracing a traditional view of the sexes, Lessing affirmed that "men and women have much more in common than they are separated"; ironically, this feminist belief put her at odds with feminists who wanted "oversimplified statements about men and women." Lessing was particularly impatient with the fixation on male sexual misconduct, mocking supposedly liberated women who "feel demeaned by a suggestive remark."

Commenting on the Edinburgh festival brouhaha, London Daily Telegraph columnist Mary Kenny suggested that Lessing's save-the-males stance reflected an old woman's maternal protectiveness. But in fact, Lessing always took a nuanced view of the battle of the sexes. Her fiction was never without sympathetic male characters, and the unsympathetic ones were often more pitiful than powerful. In the 1963 short story, "One off the Short List" (my first introduction to Lessing's work in a college class), the protagonist, a philandering husband and mediocre journalist, pursues a successful female artist for an ego-boosting conquest, persisting until she gives in just to "get it over with." The man knows he is essentially forcing the woman into bed; yet, far from being a victim, she clearly has the upper hand while he is left humiliated.

Even at her most male-friendly, Lessing acknowledged there were still women's issues to be addressed. "Real equality comes when child care is sorted out," she said at the Edinburgh event. One may quibble with her apparent belief that "changing laws" was the answer, or even ask whether full equality in this area is possible or desirable to most people (and, specifically, most women). Yet, if nothing else, Lessing raised the right questions and urged feminists to focus on actual issues instead of railing at "beastly men."

As we bid Lessing farewell, the blight she spoke of—"political correctness" and, in particular, its toxic feminist strain—is on the move again. Her trenchant critiques, which some on the left would like to brush off as mere contrarian "crankiness," should be heeded by anyone truly concerned with justice for all.