How to Get Out of the Food Stamp Trap

The food stamp program is one of the government's largest-and probably the most abused-welfare programs. But private efforts point the way out of this costly response to hunger.

Nearly 23 million people—more than one-tenth of the American public—currently receive food stamps. The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimates that another 9 million might be eligible. The program, administered by the USDA's Food and Nutrition Service, was large enough to consume some $11.1 billion in fiscal 1982 (FY 82).

From the beginning, the food stamp program has been beset by serious structural problems. Their severity and profundity indicate that far more is necessary than cosmetic change. It is time to reassess the purposes of the program and to entertain a real alternative.

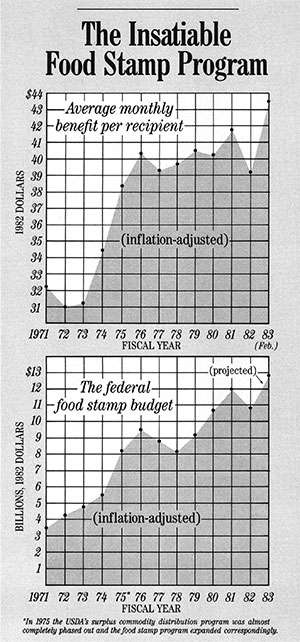

Rapid and spiraling growth has been a hallmark of the food stamp program. Since it went nationwide in 1965, its budget has increased 103 times in constant dollars. Program costs, which may climb to $12.8 billion for FY 83 if the Department of Agriculture gets its way, increased by 120 percent between 1972 and 1982 alone. And figures don't even include all the unreimbursed administrative costs incurred by states and localities, which the USDA calculates totaled another $528 million in FY 82.

Considering the enormous scope of the food program, it is instructive to recall a long-forgotten projection made in 1966 by Howard P. Davis, then the deputy administrator for the USDA's food programs. "Ultimately, when the program reaches maximum expansion," he said, "we've been figuring on 4.5 million people, covering about half the counties in the nation, and involving somewhere between $375 million and $400 million a year."

Clearly, the program was conceived of as a limited measure offering governmental relief in emergency situations. Instead, food stamps have become a permanent feature of the lives of many people as the program has ballooned.

The irony of the modest prediction of 1966 is compounded by the fact that, despite its already sizable budget, the food stamp program has frequently required funds far above spending ceilings established by Congress just to continue operating. In an effort to keep cost increases under control, in 1977 Congress passed legislation putting a ceiling on food stamp appropriations. But in 1978, the program saw a huge upsurge in the number of recipients, an upsurge that continued well into 1981. In FY 79 alone, the number rose from 15.3 million to 19.3 million, boosting program costs by about 25 percent and exhausting appropriated funds long before the end of the fiscal year. Congress allocated an additional $620 million for food stamps that year, and for several years the overriding of spending ceilings became an annual ritual. A cap of $6.19 billion for FY 80 was overridden, as was a cap of $6.24 billion for FY 81.

A frustrated Rep. Thomas Coleman (R–Mo.) complained, "The Agriculture Department claims that funds are running out because of the cap, but the real reason is that more people have been brought into the program without putting in cost-cutting requirements. At USDA, they're always going to reform tomorrow.''

Ever-increasing cost is not the only problem. All welfare programs are subject to fraud and abuse, and food stamps have been no exception. In a 1975 speech, then-Treasury Secretary William Simon called the program a "well-known haven for chiselers and rip-off artists." He was roundly criticized for exaggeration, but Buffalo, New York, District Attorney Edward C. Cosgrove confirmed in 1977, "From what we hear from the streets, every conceivable way of defrauding [the food stamp program] is going on."

Estimates of the portion of food stamps fraudulently obtained range as high as 30–35 percent. However, experts on the program, ranging from Maurice MacDonald of the University of Wisconsin's generally liberal Institute for Research on Poverty to Tom Boney of the generally conservative Senate Agriculture Committee staff, told REASON that the most reliable figures available are the Department of Agriculture's so-called error rates. The department's Food and Nutrition Service requires random audits of food-stamp applications and then issues semiannual reports on the percentages of food stamps issued erroneously by states. For the six-month period ending in September 1981, the national error rate of stamps overissued and issued to ineligible recipients was 9.75 percent—in other words, some $517 million in food stamps was issued wrongly during that time.

In addition to fraud and mismanagement, there have been anomalies in the normal operation of the food stamp program. For instance, until 1981—16 years into the program—workers who had gone on strike could obtain food stamps.

In labor negotiations, the effect of this taxpayer subsidy of voluntary unemployment was reportedly substantial. A 1970 auto workers' strike against General Motors cost between $10.7 and $14.3 million in food stamp benefits for workers on strike. And as one worker noted, "They can't starve us out now that we're getting food stamps. We can go on forever." Said another, "Food stamps are really helping out." A striking coal miner made the same point in an ABC interview: "As long as the government puts out food stamps and we can get them, we'll stay right out on strike."

The purposes of the program would seem to be distorted in other ways, as well. Department of Agriculture figures indicate that in August 1981, for instance, 10.2 percent of all households receiving food stamps had gross incomes above the poverty line. And this is not a violation of the law; recipients can have incomes as high as 30 percent above the poverty line. (The poverty line itself tends to exaggerate poverty because such "in-kind" transfers as public housing and Medicaid are ignored in calculating household income.) It's little wonder the USDA reports that 36 percent of food stamp recipients are homeowners.

Furthermore, food stamps need not be relegated to use in a grocery store. The elderly and disabled may use them to eat out in certain communal dining facilities. Stamps can be redeemed for meals served in drug and alcohol treatment centers. And in parts of Alaska they can be used to buy fishing and hunting equipment.

Outreach efforts, too, have sometimes been a perversion of the plan to provide temporary relief for the needy. Consider a 1980 advertisement in a New York subway. Two wealthy-looking women were pictured in a well-appointed apartment. The caption of the ad informed readers that they, too, could possibly qualify for food stamps.

One of the most curious aspects of the food stamp program has been the paucity of firm evidence of its efficacy. In the 1964 Food Stamp Act, which gave birth to the current program, perhaps the primary stated objective was "to safeguard the health and well being of the nation's population and raise the levels of nutrition among low income families." But during the 1970s, while the program was mushrooming in size, report after report attested to the lack of evidence about its nutritional effects.

No restrictions were placed on food that can be bought with food stamps. (They cannot be used to purchase pet food, cigarettes, or alcoholic beverages, but food for human consumption is unrestricted.) "If [food stamp recipients] choose to buy Twinkies or Coca-Colas, so be it," Rep. Ronald V. Dellums (D–Calif.) once declared in response to critics of this aspect of the program. Nevertheless, nutritional improvement is one of the program's important goals.

In 1975 a National Academy of Sciences report noted of food programs in general:

Little or no effective evaluation of the impact of these programs on the nutritional well-being of the target groups has been carried out.…There is little information with which to evaluate the continuing value of these programs.…How effective in improving the nutritional standard of the recipients are food stamps and other food supplement programs or the international food programs? This information is woefully lacking.

Maurice MacDonald of the Institute for Research on Poverty drew the similar conclusion in 1977 that "existing evidence on the nutritional effects of the Food Stamps program…is sketchy."

In 1978 a study on the relationship of food stamps to nutrition was completed by Donald West, then an agricultural economics professor at Washington State University and now with the Department of Agriculture. West's study, based on data recorded in 1972 and 1973, compared the food-buying habits of food stamp program participants and eligible nonparticipants.

Did the households receiving stamps buy more nutritious food than the other low-income households? West found no significant difference. He reported that nonparticipating households spent more on food eaten away from home, but participants and eligible nonparticipants allocated "quite similar" percentages of their food-at-home expenditures to the important food groups.

Two subsequent studies, both conducted by the USDA's Human Nutrition Information Service, did find a positive difference in the nutritive value of stamp recipients' diets. For the first study, researchers in 1977 and 1978 analyzed the diets of 4,400 low-income households, including both stamp recipients and nonrecipients, to determine how many were getting all of the recommended daily allowances for 11 nutrients. The researchers found that 38 percent of the households not receiving stamps were meeting that standard, while 48 percent of households receiving stamps were. A similar study in 1980 surveying 2,900 households found that 34 percent and 46 percent, respectively, were getting all of the recommended daily allowances of 11 nutrients.

What is not shown by the USDA studies, however, is that food stamps were responsible for the higher nutritive content of the recipients' diet. It's possible—maybe probable—that the higher nutrition levels were not due to the food stamps but rather to the households themselves, to a strong interest in healthy food and diet that was not such a high priority for the low-income households who were eligible but not receiving food stamps.

Practically speaking, the nutritional effects of the food stamp program are still not established. Maurice MacDonald recently told REASON that it would be difficult for any researchers actually to determine these effects.

While there are serious unanswered questions about the nutritional effects of the food stamp program for the recipients, there is little doubt about the program's effects on the pocketbooks of one of the nation's most powerful political interest groups—farmers. From the time the program started, the farm lobby in Washington has been one of the biggest boosters of food stamps.

The logic of their support is simple enough. As Ruth Kobell, a legislative assistant for the National Farmers Union, explained to REASON: "We assume that farmers need their produce consumed. When people don't have money to buy it, we think that programs like food stamps that help them buy food are in the national interest.…The food stamp program is a [lobbying] priority for us."

Indeed, the farm interests' stake in the program is even larger than what might appear at first glance, for two reasons that were pointed out by Kobell last March 25 in testimony to a House domestic marketing subcommittee. First, she noted that the food stamp program is "important to farmers in providing a market for many products on which there are not direct farm stabilization measures. About half of the food stamp expenditures go for commodities which have no direct Commodity Credit Corporation support mechanisms."

Second, "farmers are now receiving about 37 cents of the [typical] consumer's food dollar on average, but they tend to receive up to 60 percent of the food dollar for such food classifications [as are bought more frequently by food stamp recipients] because there are less processing costs involved."

It's no wonder that delegates to the National Farmers Union convention last winter adopted a resolution stating, "We believe all who are eligible are entitled to participate in the Food Stamp Program and that Congress should remove the 'cap' on funding." Nor is it any wonder that two of the food stamp program's most ardent champions in Congress have been Sen. Robert Dole (R–Kans.) and ex-Sen. George McGovern (D–S.D.), a mainstream Republican and liberal Democrat who agreed on little else. As Dun's Review noted, about the only thing Dole and McGovern had "in common [was] the sweeping wheat fields of their respective states." Since McGovern's 1980 defeat for reelection, other Farm Belt senators such as Mark Andrews (R–N.D.) have taken up some of the slack left by McGovern's absence.

Meanwhile, as agricultural interests benefit from a food stamp program designed to help low-income Americans, those Americans are disproportionately the victims of government agricultural policies whose explicit purpose is to keep food prices higher than they would otherwise be. Clearly, if the government wants to help low-income people to be able to afford food, one of the most significant things it could do is end its intervention in the agricultural sector of the economy.

That intervention takes numerous forms. The government pays farmers not to plant crops, so that "too much" food will not be produced, forcing prices "too low." The government maintains price supports for a whole range of agricultural products, guaranteeing that it will buy what is produced but cannot be sold at or above the support price. The government, alternatively, makes "deficiency payments" to farmers, covering the difference if the market price is lower than a "parity price." The government enforces agricultural producers' marketing orders, whereby farmers agree to restrict the quantity of foods they will sell in order to keep the prices higher. The government also limits food imports to protect US farmers from foreign competition.

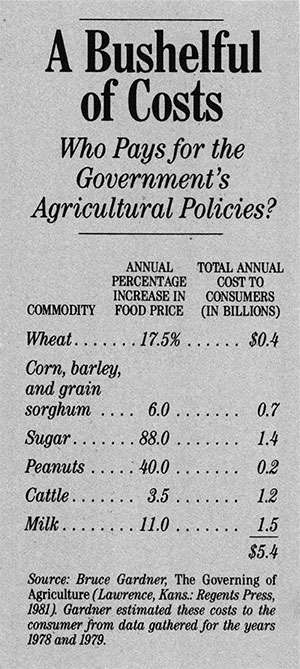

For some of these programs, taxpayers foot a bill that runs into the billions annually. And as food consumers, taxpayers pay again through higher prices—which is the purpose of all of these programs. Economist Bruce Gardner reported in his recent book The Governing of Agriculture his estimate of the cost to consumers of some major agricultural programs. In 1978 and 1979, he found, consumers paid nearly $5.5 billion more for food annually as a result of these programs (see table, page 28). This does not include the effect on prices of marketing orders that cover a wide range of fresh fruits, nuts, and other farm products. (Nor does it include the direct cost to taxpayers of various payments to farmers.)

Because poorer people spend a relatively large percentage of their income on food, the government's agricultural policies act as a powerfully regressive tax, or an income redistribution program. As Stephen Chapman recently wrote in Harper's, "it is not an exaggeration to say that, under the price support system, slum children in Harlem go without milk so that dairy farmers in Wisconsin may prosper."

Consider, for example, the USDA Commodity Credit Corporation's purchase of "surplus" agricultural commodities. In early 1983, the CCC had on hand a horde of 11.4 billion pounds of nonfat dry milk. This is enough to provide the recommended daily amount of milk—according to the USDA's own Daily Food Guide—for a whole year for more than 39 million adults (that's about 7 million more than the total number of Americans that the Census Bureau says were living below the poverty line in 1981).

Among the other commodities owned by the USDA at the end of February were 1.5 billion pounds of other dairy products, 184.6 million bushels of wheat, 1.8 billion pounds of rice, and equally impressive amounts of honey, rye, oats, corn, sorghum, and other commodities. The storage costs alone for these commodities are staggering. They vary with the size of the inventory, but Barry Klein of the USDA estimated that for its mid- April holdings, the storage costs for grains were $700,000 daily and for dairy products, $163,500.

Even the amount of food lost to spoilage and partial spoilage is enormous. Some government-owned cheese and nonfat dry milk are kept so long that they are "downgraded" (designated as unfit for human consumption). A high official of the USDA's Kansas City field office who asked to remain anonymous told REASON that the downgraded milk is usually then sold as animal feed. In a seven-month period last year, almost 39 million pounds of nonfat dry milk were downgraded.

Incongruous as it may seem, it would be considerably cheaper in the long run for the government simply to give away many commodities than to store them indefinitely. (For example, an official of the USDA's Dairy Division estimates that distributing dairy products is less expensive than storing them for two years.) Sen. Robert Dole (R–Kans.) sponsored an amendment to the jobs bill last March authorizing $100 million for processing and distributing of $1 billion worth of surplus food, with at least one-tenth of the funds going to food banks and charitable institutions for reimbursement for handling costs. The Dole proposal was considerably diluted by the time of passage, but it has resulted in the Department of Agriculture designating 9 million pounds of grains and flour and 5 million pounds of nonfat dry milk for distribution in each remaining month of FY 83.

If the government were to do away with the current tangle of agricultural price supports and subsidies, there's little question that a freer market would drive down food prices for the consumer and hence dramatically lower food costs to an affordable level for many people who now depend on food stamps. Drastic reform of the government's agricultural policies could conceivably eliminate the perceived need for food stamps as general support for low-income households. That the food stamp program was not so conceived at its inception is evident from the early estimates of the limited number of people who would receive stamps. At ever-increasing costs to the taxpayer, and with agriculture and the welfare bureaucracy building up an ever-greater vested interest in the program, food stamps have come to play a far larger role than tiding people over temporary emergencies and assisting those on the very bottom rung of the economic ladder.

One of the results of the food stamp program having grown so large is that people find it difficult to contemplate its elimination, whatever their objections because of the extent of fraud in the program or its costliness to the taxpayer. In fact, however, various sorts of existing organizations suggest the real potential of voluntary, private mechanisms for dealing with the needs originally addressed by the food stamp program.

Consumer cooperatives provide one alternative. The membership of most consumer food co-ops is predominantly middle-class. Co-ops need to be capitalized by their members, and people barely eking out a living rarely have extra funds for capitalizing a business of any kind. In addition, according to an official of the Washington-based Cooperative League of the USA, food prices in co-ops are frequently as high as—if not higher than—supermarket prices.

But there are important exceptions to the rule. Some food co-ops do serve low-income people, offering food at below-market prices. One of the largest and best-known of these co-ops is the Self-Help Action Center on Chicago's South Side. Two signs of its success are its membership roll of more than 25,000 and the low cost of the food and groceries it offers. Rob Brown, Self-Help's marketing director, told REASON that a comparison last March of Self-Help's prices with prices in six conventional supermarkets nearby indicated that shoppers could realize substantial savings on their food bills (more than 60 percent for several items) at Self-Help.

Self-Help's operation is very different from that of a typical grocery store. For one thing, Self-Help obtains food directly from wholesalers and farmers in Illinois, Michigan, Indiana, Arkansas, and Florida and passes its savings on to its members. For another, the organization is staffed largely by volunteers (executive director and cofounder Dorothy Shavers told REASON that in May, Self-Help had only four people on its payroll but also had 34 volunteers whose maximum compensation was $5 a day for coffee, lunch, and subway fare). Another big difference between Self-Help and conventional supermarkets is that when food is unattractive or missing a label, most supermarkets will throw it out—but so long as the food itself is fresh and nutritious, Self-Help will sell it.

Self-Help has had its share of problems. According to the Chicago Sun- Times, the co-op has had a few break-ins that almost forced it to close up shop, and they had "explosively mushrooming" problems, as Shavers put it, when Self-Help offered to serve without compensation as a center for the government's cheese distribution program some months ago (many of the headaches were a result of uncertainties in the delivery of the cheese and butter). Even so, the Sun-Times said that Shavers "has done a wonderful job helping feed needy people."

Another alternative to government assistance is food buying clubs, which have burgeoned all over the country. Unlike cooperatives, which operate as businesses, buying clubs are usually just a group of people who save on their food bills by buying food jointly from wholesalers.

A good example of an extensive and sophisticated buying club is the Mission Hill Food Cooperative in Boston. Its membership is not confined to low-income people, but they are an estimated 40 percent of an organization that includes people from all social and economic levels of the city. As coordinator Mary Linn Borsman says, "People join whether they're from [blue-collar] Dorchester or [middle-class] Brookline"—and they save an estimated 20 to 30 percent on food bills.

Strictly speaking, Mission Hill Food Cooperative is perhaps a misnomer. Although the organization is certainly a, network of cooperation for mutual benefit, it is less a cooperative than a confederation of buying clubs, called "blocks." Each block is made up of about 10 to 20 families who fill out food orders on a printed list every week, collate their orders into a larger block order, then deliver it on Monday night to Mission Hill. At the Mission Hill headquarters, the block orders are combined and a handful of volunteer buyers fan out across the Boston area to purchase food in bulk. They bring the foodstuffs back to Mission Hill, and on Wednesday or Thursday, each block sends a representative to pick up the block's portion of the food for distribution.

An advantage of Mission Hill's preorder system, according to Borsman, is that it permits Mission Hill to run with a far smaller staff than a fully stocked store would require. (In fact, the only paid employees are Borsman herself and a part-time bookkeeper; everyone else who works with Mission Hill is a volunteer.) Moreover, Mission Hill loses little money on wasted or spoiled food, and it doesn't incur the overhead costs of large physical facilities and stocking a full inventory.

When Mission Hill began operating some 13 years ago, "we weren't started with CETA workers or Community Development money," Borsman recalls. Since then, the co-op has received government assistance only once—the state government gave them a grant of $350 six years ago that went for a walk-in cooler. "I feel skeptical of government assistance programs for a co-op," Borsman says. "For the commitment that a co-op needs to survive, you don't go to a government for money. If the community itself actually generates the co-op, it will run because of the efforts of the people who are involved in it."

Yet another voluntary alternative to food stamps is private charity. For example, a program run by St. Patrick's parish in Arvada, Colorado, provides food to an average of about 40 families a month, with home delivery. The volunteer who delivers the food also speaks with household members to determine whether help is needed to defray other expenses, such as utility bills, that the family is having difficulty meeting.

The weekly boxes of food provided by St. Patrick's include items ranging from barley cereal and pinto beans to applesauce and bread. The amount of food in the box corresponds to the size of the recipient family, and baby food is available when needed.

Ellen Porres Heath, the director of the program, told REASON that its purpose is not to provide for people per se but "to help them out until they get on their feet." And this, of course, is a significant difference between private charity and government welfare. The incentive of private agencies is to help people get through an emergency and back to self-reliance, so that the agencies can use their resources to help others. Government, on the other hand, has a powerful political incentive to expand the ranks of the welfare-dependent and not to help them become independent—the power of a bureaucracy increases as its budget grows, and the politicians who approve the growing budgets are building a growing constituency.

An unconventional but extremely effective charity that celebrates its 50th anniversary this year is the Catholic Worker movement. In 1933, Catholic anarchists Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin started their first "house of hospitality" in New York City to provide food, shelter, used clothing, and, as one account put it, "a listening ear to the unemployed and down-and-out of the inner city." Since then, some 50 Catholic Worker communities have been formed around the country with the twin goals, says Jonathan Parfrey of the Catholic Worker community in Los Angeles, "of performing acts of mercy and getting involved in social and political change."

The Los Angeles community, like its counterparts in other cities, is involved in a wide range of charitable and political projects, including a medical clinic and legal services for residents of the city's skid-row area, a bakery, a children's playground, two large houses for people needing emergency shelter, a newspaper, and sponsorship of opposition to military contractors like North American Rockwell and government deportation of Salvadoran refugees.

But one of its largest and most important activities is providing food for poor people. This is done through a food kitchen that provides free meals and through a food distribution center near downtown Los Angeles (operated with the Missionary Brothers of Charity) that provides free sacks of groceries for families, scaled to their size and economic needs.

In acquiring food for the kitchen and distribution center, the community's members have shown considerable ingenuity. For example, according to Parfrey, "We go to the central produce terminal in Los Angeles and get crates of food that are about to be red-tagged. That means that part of it is rotten, but a lot of it is often perfectly good food. It's not cost-effective for the growers to go through the crates and rebag the good food, so we go through the crates and save the good parts. It supplies us with a lot of edible food that would be going to waste otherwise."

Besides the food from the produce terminal, the Catholic Workers receive some food as in-kind donations. For example, the local Oscar Mayer's meat-processing plant donates turkey wings, and whenever two local hospitals cook too much food in a day, says Parfrey, "they put it on ice and we give it out."

Central to the Catholic Worker movement is a deep suspicion of government and centralized power. Parfrey says that its founders were influenced by the Bible and the mutual-aid concepts of the Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin, so most if not all Catholic Worker communities do not accept any government money and even refuse to apply to the IRS for tax-exempt status. "Gifts to our work are not tax-deductible," says its Los Angeles newspaper. "We are convinced that justice and works of mercy should be acts of conscience which come at personal cost, without government approval, regulation or reward."

In recent years, some "social entrepreneurs" have developed an innovative approach to expand the ability of charities to help the poor with food. In effect, a division of labor among charities has naturally evolved with the creation of new institutions called food banks. These organizations solicit food from growers and manufacturers, warehouse it when necessary, and transport it to agencies that distribute it to the needy.

Reportedly one of the first to be established was St. Mary's Food Bank in Phoenix, a modest operation when it was begun informally in the mid-'60s by John van Hengel and other Phoenicians. Today, it supplies some 3 million pounds of food a year to nearly 250 agencies in the Phoenix area, according to public relations director Priscilla Scheid.

Scheid explained to REASON that, like some other food banks, St. Mary's has a limited and separate program of its own for direct distribution of food to people in need. Each of its food boxes contains enough food for about 36 meals and usually includes produce, canned goods, cereals, peanut butter, soup, meat when it's available, and a selection of whatever other food has been donated. But the bulk of St. Mary's operation is supplying food to other agencies for distribution.

Columnist Colman McCarthy recently described another food bank, the Food Salvage Project, in New Haven, Connecticut. McCarthy noted that the group's van "travels to supermarkets, restaurants, and bakeries and there picks up food that is dumpster-bound. The haul is then distributed to 18 agencies [including] four soup kitchens."

Characteristic of such voluntary, community efforts, no one knows how many food banks there are in the country. But they seem to be on the increase, and in 1976 a sort of "super food bank"—a network of some of the food banks—was organized to acquire and distribute food to individual food banks across the country on a large scale. Called Second Harvest, it emerged from John van Hengel's experience with St. Mary's Food Bank.

Mary Titcomb, Second Harvest's communications director, told REASON that the network currently has 45 member banks. In 1982, they distributed about 60 million pounds of food, 30 million of it obtained through Second Harvest. The average member bank distributed food to 190 agencies. Contributions to Second Harvest last year included 37 railroad-car loads—about 107,000 cases—of discontinued varieties of Nutri-Grain cereal from Kellogg Company and 2.4 million quart bottles of discolored but perfectly drinkable grapefruit juice.

Second Harvest last year went through a turbulent period after van Hengel was replaced by Jack Ramsey, a former bureaucrat with the now-defunct Community Service Administration. (In 1975 van Hengel had succumbed to agency pressure to accept a CSA grant to help get other food banks started nationwide. The grant money continued to flow, and in 1981 the CSA did a routine evaluation. The report, however, coauthored by Ramsey, was critical of van Hengel's management, and questions of conflict of interest arose when Ramsey soon thereafter was hired to replace van Hengel.) But the fact remains, as the Wall Street Journal concluded in an article last October, "By most standards Second Harvest has been a raging success."

Examples such as these show that when people are skeptical about the viability of private alternatives to vast government programs like food stamps, that skepticism may well be ill-informed. If people are already willing and able to do so much, even with that government program in place, what might they accomplish if the government withdrew its assurance that citizens need not worry about those in need—"Uncle Sam is taking care of it"?

"I agree with Ronald Reagan that we need a heightened sense of voluntarism in this country," says Catholic Worker Jonathan Parfrey. "I probably don't agree with him on anything else, but he's right about that."

That spirit of voluntarism is already alive. It animates countless individuals to pool their efforts and energy for mutual benefit and to help others in need. It undermines the conventional notion that unless a welfare state coerces its citizens into being generous, the less-fortunate will be starving in the streets.

David Lips is a student in law and business administration at Duke University. This article is a joint project of the Sabre Foundation Journalism Fund and the Reason Foundation Investigative Journalism Project.