Pockets of Free Trade in an Unfree World

Go east young man

Postwar government policy worldwide has been to intervene more and more in economic affairs, with an attendant rise in taxation, higher rates of inflation, and recession. However well-intentioned, the true effect of such intervention is that individual economic freedom is suffocating under the heavy hand of public regulation and inquisitorial systems of high rates of taxation.

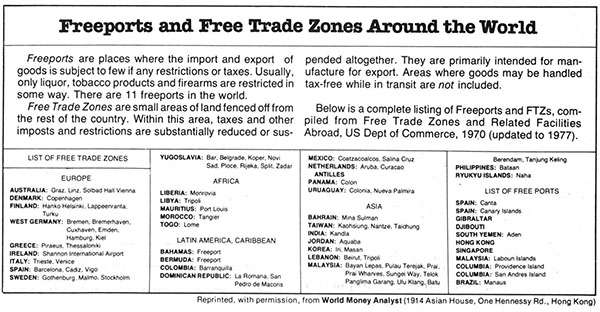

The Pacific Area Basin has not been immune to this postwar trend of bigger government: government regulation, public economic activity, and outright planning have retarded economic growth in such nations as India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia; planned economies are the rule in Communist China, North Korea, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and Socialist Burma. But a contrary trend has emerged in the same region of the world—one that takes the form of greater economic liberty and individual freedom. I refer specifically to the resurgence of "free-trade zones," also called "export-processing zones."

Finding pockets of free trade in an unfree world is not new. Francis Light occupied Penang in 1786 and began the free-port tradition. Sir Stamford Raffles followed suit and declared Singapore a free port upon its transfer to British authority in 1819. Hong Kong enjoyed free-port status upon its founding in 1841, as did the island of Labuan off the north coast of Borneo when it came under British administration in 1846. Other British free ports existed under colonial administrations in Tangier (1662), Gibraltar (1705), Malta (1801), the Ionian Islands (1814), and Minorca (1824); and economic liberalism is still official economic policy in the Cayman Islands and Bermuda. The former colonies of Aden and the Bahamas were free-port regimes under British administration.

Since the mid-1960's a number of leaders in Asia have rediscovered the precept that economic freedom and rising prosperity go hand in hand. Taiwan best illustrates this post war story, but freedom and prosperity are contagious phenomena: free-trade zones have cropped up in the Philippines and Korea—and even in such unlikely locations as Liberia, Mauritius, and Egypt.

Let us pick up the story in 1945, when the island of Taiwan was returned to the Republic of China. Immediate postwar years were dominated by politics and military events. Since 1949, however, economic and financial officers in Taiwan's government have encouraged private enterprise. In 1954, for example, the government transferred to private ownership four large state-owned enterprises engaged in the production of cement, pulp and paper, industrial machinery and mining, and agricultural and forestry projects.

What were the motives underlying the establishment of an "export-processing zone"? First, Taiwan faced a phasing out of US economic aid. Second, Taiwan wanted desperately to attract more domestic and overseas investment capital to accelerate economic growth, create new job opportunities, and increase the nation's foreign exchange earnings. In the light of these priorities, export-processing zones emerged as a very appropriate vehicle to attain these goals and in the process increase economic opportunities and promote individual economic welfare.

What are the incentives that attract investment in the zone? The EPZs exempt customs duties on importation of raw materials, parts, and machinery and on exportation of finished products. Investors pay neither sales nor commodity taxes and enjoy a five-year tax holiday on corporate income taxes or an accelerated depreciation rate on fixed assets. Simplified procedures do away with red tape and bureaucratic procedures: the EPZ Administration is authorized to act for various government agencies and handle all phases of operations within the zone. These include investment application processing and approval, import and export licensing, foreign exchange settlement, company registration, and so forth. Taiwan's EPZ combines the features of a free-trade zone and an industrial area; it provides both liberal economic incentives and the necessary facilities to conduct all import and export procedures under one roof.

Free trade has made an important contribution to Taiwan's economic well-being. The Kaohsiung Export Processing Zone (KEPZ) was inaugurated on December 3, 1966, and all 69 hectares of land within its walls have been fully utilized by 143 export enterprises. To accommodate excess demand, the government opened two more zones in 1969, the Nantze Export Processing Zone (NEPZ) and the Taichung Export Processing Zone (TEPZ). NEPZ, also located in Kaohsiung, has a fenced-in area of 90 hectares; it is designed to accommodate about 200 export enterprises and is well over half subscribed. TEPZ, the smallest of the zones with but 23 hectares of land in central Taiwan, has admitted 44 export enterprises for production and is now at saturation point.

Trade figures reveal the dramatic economic benefits of the export-processing zone. In 1976 economic activity in the zones accounted for seven percent of Taiwan's total foreign trade. Far more significant are the overall balance-of-trade figures. In 1976, fully 62 percent of the nation's favorable trade balance was attributable to the economic activity in the zones, which only generated seven percent of the total volume of foreign trade.

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, Taiwan's economic policy is indeed flattered. Other Asian nations have established similar zones in their own countries along the lines of Taiwan's export-processing zones.

Korea established its Free Export Zone to encourage direct foreign investment in exports. The Masan Free Export Zone was set up in 1970, followed by a second FEZ at Iri four years later. Investors in the zone are guaranteed free overseas remittance of profits and dividends from the first year of operation; occupant enterprises are exempt from income, corporation, and property taxes for five years and enjoy a 50 percent reduction of taxes for the succeeding three years. (Korea's conditions are clearly competitive with those in Taiwan.) Simplified procedures minimize delays in the zone. In fact, the rules and regulations mirror those found in Taiwan. The Masan FEZ is an extraordinary economic success—the city of Masan literally doubled in population between 1971 and 1974. Just over 100 enterprises achieved US $174 million in exports in 1975.

Nor has the Philippines let its neighbors go without competition. The Bataan Export Processing Zone (BEPZ) was established in 1969 with a total area of 1,598 hectares to encourage industrial investment. Firms located in the BEPZ are exempt from municipal, provincial, and export taxes and benefit from accelerated depreciation rates on fixed assets as well as tax-free and duty-free importation of machinery, equipment, raw materials, and supplies. Operating losses incurred in the first five years of operations can be carried over as deductions from taxable income during the succeeding five years. Again, red tape is minimized in the zone.

Malaysia, too, has created a number of free-trade zones. Beginning with the establishment in 1972 of the Bayan Lepas Free Trade Zone, Malaysia has announced the formation of nine distinct free-trade zone areas in the provinces of Penang, Selangor, and Malacca. This decision to set up so many free zones in Malaysia doubtless reflects the success of the zones in Taiwan, Korea, and the Philippines. In the struggle to compete for foreign investment, the free-trade zone is fast becoming a crucial element of economic policy.

Nations outside Asia have also noticed the success of Taiwan's EPZs and its rivals in Korea, the Philippines and Malaysia. Liberia recently completed a feasibility study for the establishment of an industrial free zone to encourage duty-free privileges and tax holidays for export-oriented industries. The United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), set up as a branch of the United Nations in 1967 to help member states with industrial development, has within its organizational structure a "free zone unit" that gives technical assistance on the establishment of free-trade zones. Its 1974 Annual Report states that the following countries asked UNIDO to help draw up plans for such zones: Gambia, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Senegal, Jamaica, Syria, Trinidad and Tobago, and the Sudan. Since 1974 the Egyptian government has been considering the creation of a Hong Kong-style, low-tax, duty-free industrial-port city on the Suez Canal.

In the past two years, further announcements confirm the growing popularity of free-trade zones. On October 15, 1975, the Azores announced its plans for a duty-free port. In late December 1976, the Italian parliament approved a treaty allowing a free-trade area in Trieste. Finally, the victor in Sri Lanka's national election of July 22, 1977, J.R. Jayewardene, described in his first news conference plans to set up a 200-square-mile free economic zone in the country as a matter of urgent priority.

This rebirth of free trade and its manifest attendant prosperity encourages even governments with heretofore controlled economies to open their doors to free trade within their own territories. Socialist policies in Sri Lanka now give way to greater reliance on free enterprise. Taiwan has recently extended tax holidays in its zones from five to eight years to compete with Korea's provisions. In the future, more and more investors will monitor facilities and services in the world's free ports and trade zones. Commensurately, more and more nations are likely to set up free-trade zones to attract foreign investment.

I suspect that economic freedom is a contagious phenomenon. The prosperity that emanates from the several Asian zones may induce the governments of these countries to follow economic policies that move in the direction of greater economic freedom for all its residents, both in and out of the zones. Nineteenth-century Western economic policies of nonintervention in private economic affairs may soon come to describe later 20th century economic policy in Asia.

This rediscovery of free trade is likely to be accelerated if the economies of the West continue to perform poorly. Western capital will seek to escape increasing taxes and restrictions by investing in freer Asian countries. The resultant economic growth and increased incomes will increase trade between Asian nations, reducing the importance of the West to Asia's well-being. Groupings such as ASEAN—which could form the nucleus of an Asian free-trade area—may well hasten this growing Asian trend.

Adam Smith has now come to Asia—to the benefit, I might add, of its millions of inhabitants. And who knows—perhaps the success of economic freedom will spur repressive governments to loosen their grip on other areas of people's lives.

A senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, Professor Rabushka is the author of The Changing Face of Hong Kong and A Theory of Racial Harmony.