Why Carter's Game Plan Won't Work

Lord Tweedsmuir's widely quoted statement, "Those who do not know history are condemned to relive old mistakes," could not be more apt than at the present moment. We are reliving some old economic mistakes—and these mistakes are impeding recovery. We can learn which of our current policies are mistaken by an examination of history. In particular, we can learn that current Federal spending and the resultant deficit, which are supposed to be aiding recovery, are actually impeding it. We can learn from history that fiscal stimulus and deficit spending are not the royal road to prosperity.

Jimmy Carter is urging increased government spending as a means of speeding recovery. Yet that is the remedy that failed from 1933 to 1935 when the Great Depression was prolonged by two years beyond the recovery that occurred everywhere else in the world. The prolongation was the result of a series of measures that included stepped-up Federal spending. The 1933-35 failure is not as clear and obvious as several later failures, however, because so many other "social experiments" undertaken at the same time make it difficult to pin the donkey's tail on fiscal policy alone.

The experience of 1948-49, however, is very clear. There is no doubt that deficit spending failed to produce the expected consequences in 1949. It failed to produce the runaway boom that was confidently predicted by the fiscal ideologues and it failed to prevent a recession. Despite a marked increase in fiscal stimulus in 1948 and 1949, recession occurred in 1949. In 1948, there was a $12 billion swing in the Federal budget, in the direction labeled "stimulus" by the fiscal ideologues. That presumed shot in the economy's arm was the result of a tax cut, enacted by Congress in April 1948, and of increased spending. Those who believe that increases in spending relative to tax collections stimulate the economy were so worried that a runaway boom and inflation were going to follow this $12 billion swing in the Federal budget (equivalent to a $75 billion increase in today's budget) that they persuaded President Truman to veto the tax cut. Congress overrode Truman's veto.

The believers in the influence of fiscal policy continued to worry about the economy becoming overheated with a runaway inflation. They persuaded Truman to call a special session of Congress, in August 1948, to impose price controls. Congress refused to do so. In spite of all the predictions that fiscal stimulus was going to produce a runaway inflation, consumer prices fell by 5 percent and wholesale prices by 10 percent in the following 16 months. Instead of booming, the country slid into a recession in late 1948. Prices peaked in August 1948 at the very time that Congress was called into special session.

The believers in the notion that the fiscal policy tail can wag the national dog should have known better than to make their 1948 predictions—predictions which turned out to be the exact opposite of what materialized. They had failed just as miserably in predicting what was going to happen in 1946 after the most enormous shift in fiscal policy which has ever occurred in our history. If ever there was a test of the fiscal ideology, 1946 was it, and fiscal ideology flunked. If Federal spending makes the economy go, someone forgot to tell the economy it was supposed to stop in 1946.

In 1945, the believers in the Federal spending theory of prosperity predicted that 1946 would see us suffering from 8 to 12 million unemployed because of the great cut in government spending following the end of World War II. Federal outlays were sliced by $60 billion in 1946. That is equivalent to a $400 billion reduction in Federal spending in today's economy. The drop in government spending—which was supposed to be followed by a depression of 1933 proportions—was actually followed by such a rapid employment rise in industries producing civilian goods that, despite the release of people from the armed forces and from the armament industries, we were complaining about shortages of labor and over-full employment in 1946. Less than 3 million were unemployed—not 12 million. The number unemployed was less than would be expected in periods of normal prosperity considering the time taken by new entrants to the labor force to locate their most desired jobs and by voluntary quits who spend time finding jobs more desirable than those they quit. Also, many of the unemployed were members of the 52-20 club who were unwilling to lose their membership by taking a job. Evidently, it is not government spending which keeps the economy going.

The fiscalists who believe that deficits stimulate and surpluses depress the economy should also be forced to examine the history of the 1920's. They should tell us how it is, if Federal surpluses depress the economy, that the economy managed to boom. How did the country manage to keep setting new employment records when we had a terribly "depressing" Federal budget? How did output keep increasing despite annual surpluses in the Federal budget sufficient to reduce the national debt from $25 billion in 1921 to $16 billion in 1919? (That is equivalent to a $25 billion annual surplus in today's Federal budget.) How did employment manage to grow from 40 million in 1921 to 47 million in 1929? How did the real GNP manage to "creep" up by 46 percent (an annual growth of 5 percent) in that eight-year span of naive, old-fashioned belief in balancing budgets and paying off debt?

Currently, the Federal government is running a near record-breaking deficit, over $50 billion annually, yet the unemployment rate has been rising—from 7.3 percent last May to its recent 7.8 percent level. If large deficits could do the job of restoring full employment, the recovery from the 1974 recession should have been completed by now. But it hasn't been. Deficits as a nostrum for unemployment have failed repeatedly, are currently not affecting a cure, and yet more of the same is being urged. The unemployment physicians are behaving like those who treated George Washington. When a little bleeding failed to cure, they tried more bleeding, and then still more—and killed their patient.

But we are being told that this past recession and the current recovery are like no other cyclical episode in U.S. history. Who ever saw double-digit inflation during a period of falling economic activity and employment as we did in 1974? Who ever saw declining interest rates during a recovery such as we have seen during the past 18 months? Interest rates are supposed to slide during a recession and recover during an upturn. Interest rates did slide during the downturn, although they did not begin their slide until eight months after the recession began. The prime rate dropped from 12 percent in July 1974 to 8¼ percent by April 1975. That is when the recovery began. But the prime has continued to drop, from 8¼ percent last year to 6¾ percent currently. The Fed Funds rate has dropped even more sharply, from its 13 percent peak in July 1974 to 5 percent currently, 18 months after recovery began.

The interest rate slide has been in the face of a recovery which has seen civilian employment rise from 84 million in March 1975 to 88 million currently. Current employment exceeds our previous peak of 86 million jobs in mid-1974 by 2 million. So here we are with a record number of jobs and a record increase in number of jobs for any 18-month period, yet with a high unemployment rate, with declining interest rates, and with depression-fighting measures being urged in the midst of a recovery that is already well under way, by nearsighted politicians who can see no farther forward than the nearest elections and no farther back than the last boom—if that far.

Is this faltering recovery something which requires special measures to keep it going? Should we apply the New Deal measures which failed in the 1930's to meet the employment problems of the 1970's? Should we enact a Humphrey-Hawkins bill as the Democrats urge? Should we enact more public works programs to re-employ the 15 percent of construction workers who are unemployed as George Meany urges? Should we prepare to clamp on price controls as Jimmy Carter's advisers believe may be necessary?

Of more immediate concern, should we be following the advice of Professor Larry Klein, Mr. Carter's prime economic adviser? He is urging the Federal Reserve to reduce interest rates by pumping more money into the economy. He thinks the current recovery is being throttled by high interest rates. He wants to spur the economy by reducing interest rates. But there is a fundamental question to be asked. Will Dr. Klein's proposed money policy reduce interest rates—or will it raise them?

Here is where a little history can help us avoid a great mistake in policy which is being urged by Mr. Carter's economic adviser. If we follow Dr. Klein's advice, we will end up with higher interest rates—not lower rates—and we will re-ignite a more rapid inflation after paying a very high price to reduce the rate of inflation from its 12 percent annual rate two years ago to its current 6 percent rate. To throw away a victory half-won at this point is the height of folly and irresponsibility.

Now what is it that history can tell us about the effect on interest rates of a step up in money growth? The first effect is that predicted by Dr. Klein—what we can call a liquidity effect. Unexpected increases in cash flows do cause a decrease in short term interest rates for five to eight months.

Dr. Klein would say, "Fine. That is exactly what we want. With lower interest rates, business will borrow more to carry more inventory, to buy more machinery, and to put up more plants. Developers will borrow to erect houses and apartments. The rise in autonomous spending will generate a multiplier effect which will increase GNP by a multiple of the increased investment spending. That will increase tax collections and the Federal deficit will be eliminated by the rise in tax collections."

This hypothetical quote from Dr. Klein may be good theology, but it is lousy economics and it is contradicted by historical experience.

Our historical experience tells us that usually within eight months after money growth is unexpectedly increased, interest rates will turn up. In another five to eight months, they go back to the level prevailing before the increased money growth began. After that, they exceed the earlier level. The rise, after the initial fall, is a consequence of two effects of increased money growth. One can be called the income effect. Three to five months after an increase in money growth rates, nominal incomes start rising, increasing the demand for goods. Rising sales lead business to start borrowing more to increase production. The rise in business borrowing causes interest rates to start rising.

In addition to the income effect, there will also be an inflation effect. The increased demand for goods starts prices rising. Historically, we find that every extra one percent added to the rate of inflation adds, with a lag if there has been a long period of price stability, one percentage point to interest rates. In the current situation, which follows a long period of inflation, the lag in the inflation effect on interest rates will not be long—something less than two years.

Dr. Klein's prescription for producing lower interest rates, then, will produce higher interest rates—exactly the opposite of what we want. The use of his prescription in 1971 and again in 1972 pushed our interest rates to astronomic levels in 1974 and 1975. That is why they are still at extraordinarily high levels by historic standards.

Dr. Klein's medicine is even worse than what I have already described. He wants to prescribe not only higher money growth to lower interest rates but also larger deficits to lower unemployment. If the government borrows more, however, then interest rates will move to higher levels—not to lower levels. If the Federal government were not borrowing so much currently, interest rates would not be as high as they are. The way to get lower interest rates is to reduce government spending—not increase it. By cutting Federal outlays for public works, for example, the money the government is now borrowing would be left available for residential and commercial construction. The volume of private construction is as low as it is because private builders are being crowded out of the money market by government borrowing (and construction is also being depressed by the constant increase in minimum wage determinations for Federal construction being made under the Davis-Bacon Act).

Some of this crowding out is a direct effect of government leaving so little money in the financial markets. Some of it is an indirect effect produced by reducing the net worth of stockholders. One of our studies at the University of Chicago shows that the value of common stocks held by individuals has a direct impact on the demand for residential construction. When the stock market drops, this reduces the net worth of individuals and the proportion of their portfolios held in common stocks. The drop in net worth reduces their demand for owned housing and for rental housing as a part of their investment portfolios. Whatever amount the government adds to its construction budget will be offset by a decline in private construction and private spending on other capital goods below what they would otherwise be as a consequence of direct and indirect crowding out effects.

You may have noticed in 1974 that every time an announcement was made that the Treasury's expectation as to the amount it would need to borrow was being increased, the stock market dropped. That is the direct result of "crowding out" in the financial markets. With more money being taken by the Treasury, less was left to buy stocks and the demand for stocks dropped. An indirect result was that housing starts dropped all during the period of the decline in the stock market. The effect, then, of the Treasury borrowing to finance more public works was a drop in private construction.

But here we are in the midst of a slowing in the rate of recovery that worries everyone and delights no one except Mr. Carter. All I have done is to tell you that the standard remedies will not cure us. So what is to be done to speed the recovery?

Let us look at two sides of the coin in order to get at this problem. First, why the current slowing in the recovery rate—the drop from 9 percent real growth in the first quarter to less than 4 percent currently? Then, what does the answer to this question imply about the appropriate measures to end the slowing and speed the continuation of the climb out of recession?

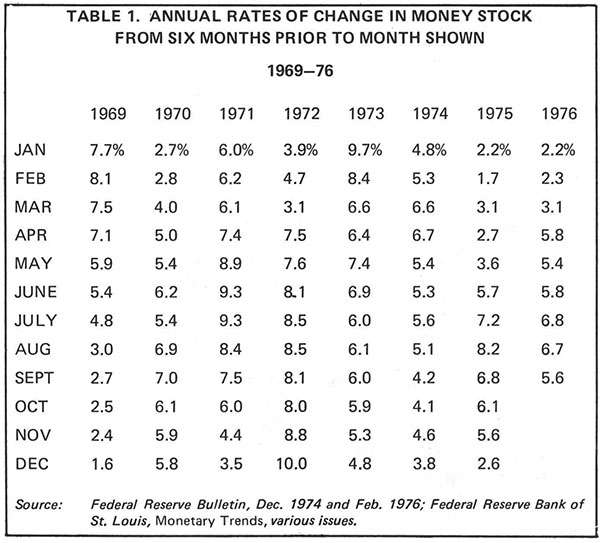

There are two aspects to the current phase—monetary policy and wage rate behavior. Looking at the behavior of money growth rates (see Table 1), you will find that the six-month money growth rate peaked in August 1975 at 8.2 percent (on a one-month basis, it peaked in June at 15.1 percent). It then slid month after month to 2.6 percent in December (on a one-month basis, the annual rate of growth in December was minus 3.2 percent) and bottomed at 2.2 percent in January, 1976. That was five months of a declining rate of money growth. Now what is important about that?

Let me tell you about a very crude forecasting rule that works fairly well. Any time money growth rates decline persistently month after month, you can expect economic growth to start slowing 6 to 9 months later. If the money growth rate decline continues for 12 to 14 months, you can expect a downturn in the economy 12 to 15 months after the decline in money growth rate began. Currently, that would mean that if the slide in money growth rates which started in August 1975 had continued up to now, we would be on the verge of a downturn in the economy. That's a lesson which history provides which has been substantiated time and again.

The recession that began at the end of 1973 was preceded by a slide in money growth rates from a 10 percent peak in December 1972. The money growth rate slide did not bottom out until February 1975. The economy hit bottom only two months later and began an upturn within three months. The point here is that the 1974 recession was predictable and its depth ascribable to the long continuation of the slide in money growth rates.

The 1970 recession was preceded by 13 months of declining money growth rates. The 1960 recession was also preceded by 13 months of declining money growth rates. This story can be repeated for every recession where we have data on monthly changes in the stock of money in the period preceding the recession.

The current slowing of growth also has historical analogues. We had a similar pause in 1955 when we were on our way out of the 1953-54 recession. That pause was preceded by a nine-month decline in money growth rates that began 10 months earlier. And do you remember the economic pause in 1962 that became known as "the pause that didn't refresh?" It was preceded by an eight-month decline in money growth rates. And there is the mini-recession of 1967 when we actually had a dip in real GNP for a few months that didn't last long enough to be officially labeled a recession. That, too, was preceded by an eight-month slide in money growth rates.

But to come back to where we are, I told you that if the money growth rate slide, which started from an August 1975 peak, had continued up to now, we would now be slipping into recession. But it didn't continue! It bottomed out in January 1976. The slowing of the economy's rate of rise is about to end. The beginning of this year should see a resumption of a higher rate of recovery by the end of the quarter with short-term interest rates bottoming. Long-term rates will remain soft provided the rate of inflation continues to move down. With the recent rate of money growth, however, it is not likely that the rate of inflation will fall any further for the next six months.

What I have described to you is an empirical observation drawn from history. If there are no causal relationships underlying this correlation, then it is no better than a sunspot theory of business cycles. Ad hoc correlations have a way of breaking down soon after they are observed. But this empirical regularity is a more than an ad hoc correlation.

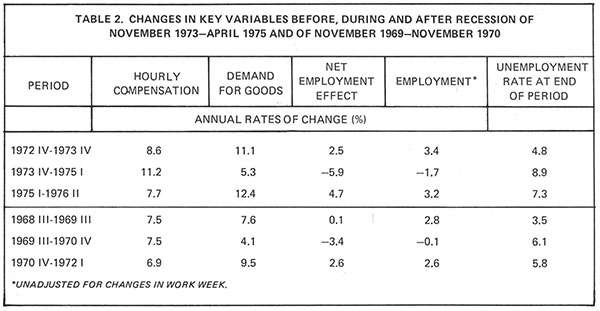

There is a theoretical, empirically verified underpinning for this historical regularity. When the money growth rate slows, expectations take about a year to adapt to the new circumstances. As a consequence, prices and wage rates continue to rise at rates which cannot be supported by the forthcoming growth of demand. In 1973, the demand for goods rose by 11.1 percent. Of this 11.1 percent rise in outlays to purchase goods, 8.6 percentage points were absorbed by a rise in hourly compensation. Businesses bid for scarce labor to meet the rising demand, and wage rates rose. Despite the large wage rise, 2.5 percentage points of the growth in demand remained to employ more labor, absorbing the additions to the work force.

In 1974, the slower rise in money meant a slower rise in spending and a slower rise in the demand for goods. The demand for goods rose by 6.9 percent. If nominal wage rates had not gone up, there would have been a 6.9 percent rise in employment. If wage increases had been restrained to 6.9 percent, employment would have been maintained at its old level and real wage rates would have gone up instead of declining. But expectations of accelerating inflation (price controls ended in April 1974) led to employers raising wage rates and agreeing in union bargaining to wage increases averaging 10.8 percent. That outran the rise in demand for goods and for labor by nearly four percentage points. That caused unemployment to rise from a normal 5 percent to nearly 9 percent (see Table 2). This wage rise outrunning the rise in demand continued into the first quarter of 1975. Employment continued to fall right into March as a consequence. Hourly compensation rose at a staggering 13 percent annual rate in the first quarter of 1975. The 1974-1975 recession can be directly blamed on an overly rapid rise in nominal wage rates. People were priced out of the labor market. That caused a two million decline in number of jobs.

The relationship of wage increases and demand increases reversed in the second quarter of 1975. The rate of wage rise slowed to seven percent. The demand for goods rose by 10 percent. The result of the slower rise in wage rates meant that 3.4 percentage points of the increase in demand went to employing people more hours per week and to employing more people.

From the first quarter of 1975 to the first quarter of 1976 we had a 13.1 percent rise in the demand for goods. If the wage rate rise had been restrained to only five percent, full employment would have been restored by the first quarter of 1976—that is, the unemployment rate would have dipped to five percent and men and women would have been working full work weeks. But the wage rise was not restrained to that level. Hourly compensation rose by 7.8 percent, leaving only 5.3 percentage points of the rise in demand to employ more people and to employ them more fully.

Restoring full employment requires a more moderate rate of wage rise. When Mr. Meany rumbled about Mr. Ford's failure to cure all our employment problem, he should have looked to his own glass house instead of throwing stones at Mr. Ford. He and his union cohorts should be providing the leadership to convince their membership that wage restraint will do more for restoring employment for their out-of-work fellow members than any government can do.

Our employment problem—or rather our unemployment problem—is not one that can be solved by government. It is up to employers to avoid giving large wage increases that are inconsistent with restoration of full employment. It is up to employers to resist union demands for unwarranted rises. It is up to union leaders to educate their membership that unwarranted wage increases cost their fellow workers the tragedy of long spells of unemployment. And it is up to all of us workers to recognize that while we all merit bigger wage increases than we are getting, bigger ones cannot be granted without creating tragedies for fellow workers. As a matter of fact, if our nominal wage rates were to rise more slowly, our real wage rates would rise more rapidly, paradoxical though this may appear to be.

If we want our real compensation to rise more rapidly and if we want to restore full employment, let us insist that Mr. Carter reduce government spending. We must reduce government spending in order to stop the drain of capital going into financing deficits—capital that would otherwise go to building and modernizing more factories and shops, providing more jobs, increasing productivity, and raising output. That will raise our real rates of pay even while we accept a smaller rise in our nominal pay.

Let us learn once again to balance government budgets. Let's repeat our historical successes, not our old mistakes!

Yale Brozen is professor of business economics at the University of Chicago's Graduate School of Business, and an adjunct scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C. This article is adapted from Prof. Brozen's presentation last fall at the Operations Management Conference of the Dealer Bank Association.