Trends

BYPASSING THE MAILS

As postal rates approach a new upward leap, magazine publishers continue to experiment with private enterprise alternatives, and the latest results look encouraging. A 3½ year test of home delivery of magazines was recently concluded by Select Magazines, Inc. in Hagerstown, MD. As many as 26 different magazines were involved, and a whole network of routes and carriers was developed. The magazines were delivered to subscribers in bunches, once a week. SMI president Tom Cahill concluded, "It could have been profitable on a large scale, and we have the [nationwide] network of 600 wholesaler-distributors that could be utilized for it on a national basis."

McGraw-Hill's Medical World News is currently using private mail delivery to groups of doctors located in hospitals and medical centers, and the company is expanding the system. Eventually McGraw-Hill expects that up to 80 percent of its circulation will be handled outside the postal system, at savings of about 20 percent. The Wall Street Journal is currently testing private mail delivery in Boston, Los Angeles, and several other cities.

Another major test of home magazine delivery is being expanded substantially this fall. National Postal Service, Inc. of Saratoga, CA is adding 200,000 more San Francisco Bay Area homes to the 60,000 already covered in its experiment. It has also added Time and Ladies Home Journal to its list of participants, which includes Reader's Digest, McCall's, and Better Homes and Gardens. NPS's president Peter Olson says the service is not yet saving the publishers money, but he expects that it will save "substantial sums in the future if postage rates keep on going up." Olson's delivery system involves use of a computer to generate delivery lists from magnetic tape lists of subscribers. No address labels are needed, saving the publisher that expense.

Large publishers are being "inundated with delivery ideas from people who think they can beat the post office rates," says Robert Nelson of Reader's Digest, proving once again the value of the profit motive in getting things done. Once magazine delivery is accepted as the province of private enterprise (as much of third and fourth-class mail now is), the way will be clear for a final assault on the postal service's monopoly on first-class mail.

SOURCES:

• "Magazines Seek Alternatives to Postal Delivery," UPI (New York), Jul. 27, 1975.

• "Publishers Sort Out Ways to Bypass the Mails," Business Week, Aug. 4, 1975, p. 64.

THREATS TO DRUG RESEARCH

A variety of actions by the Federal government is seriously threatening the ability of the U.S. pharmaceutical industry to develop new medicines. Fortunately, these regulations and programs are increasingly being exposed to public criticism.

The first major disincentive is the huge cost of getting new drugs approved by the FDA, due to the 1962 Amendments to the Food and Drug Act. Prof. David Schwartzman of the New School for Social Research has found that the average cost of developing a new drug has increased from $1.3 million in 1960 to $24.4 million in 1973. At the same time, the average rate of return from investment in drug research has dropped from 11.4 percent in 1960 to only 3.3 percent today. If this low rate continues, he warns, investment in new drug research will continue to fall off. In fact, the current picture is worse than these figures indicate, since current drug industry profits are largely the result of investments made in the 1950's and 1960's, before the full effect of recent FDA regulations.

Another threat to new drug development is HEW's recent decision to reimburse only the cost of generic drugs for Medicare and Medicaid patients, under its new Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) program. Generic drugs, while having the same chemical formula as brand-name drugs, are not always equally effective, as a recent study by the Office of Technology Assessment confirmed.

However, they are cheaper than brand-name drugs, since the latter are priced high enough to recover the developer's research and development (R & D) costs. (Companies producing generic drugs typically have small R & D budgets, relying largely on the large firms to develop drugs which they then copy, either under license or after the patent has expired.) One of the opponents of MAC, Dr. Jonas Salk, developer of the polio vaccine that bears his name, states that MAC "will have untoward consequences upon research supported and conducted by the pharmaceutical industry, without which the remarkable progress in medicine and health care made in this country would not have been possible." Twenty-five national and state medical specialty societies opposed passage of MAC, as did 85 state and county medical societies and 55 pharmaceutical societies and associations, all to no avail.

The FDA is furthering this attack on drug industry investment by its recent policies disregarding the patent rights of drug developers. Hoffman-LaRoche has filed suit against the FDA for granting permission to Zenith Laboratories to begin producing a generic version of Librium a full year before the former company's patent expires. (It has filed suit against Zenith, as well, for patent violation.) According to a recent article in Private Practice, the Librium case is not unusual. "The FDA's unofficial policy, in direct reversal of its official policy, encourages imitation drugs to be marketed illegally," states reporter Patricia Coyne. In so doing, it is threatening not merely the quality of drug products (by encouraging manufacture of not-always-effective generic drugs), but the long-term emergence of needed new drugs. For if the developers of new drugs are not allowed to profit from their efforts, this vital R & D will dry up. Whether enough voices will be raised in time to reverse these policies is an open question.

SOURCES:

• The Expected Rate of Return from Pharmaceutical Research, David Schwartzman, American Enterprise Institute, May 1975.

• "Finch Position on Drug Rules," Los Angeles Times, Aug. 7, 1975.

• "No More New Drugs?" Patricia Coyne, Private Practice, Jul. 7, 1975, p. 30.

CALIFORNIA WELFARE REVOLT

What began in tiny Plumas County (12,700 population) in northern California has turned into a widespread protest against Federally-mandated social welfare programs. At issue is the growing burden on state and local governments due to Federal programs which require state or local government spending. In many counties, a substantial percentage of the total budget now consists of such mandated items, over which local officials and taxpayers have no control.

Last May the Board of Supervisors of Plumas County voted unanimously to withdraw from participation in 11 such Federal programs, by refusing to pay the local government share. The Supervisors were reacting to widespread public resentment over the growth of the County's welfare rolls from 1128 to 1540 people over the past nine months, thanks in part to an increasing number of college students receiving Food Stamps and other forms of welfare. Fearing that the County's action could jeopardize Federal welfare funds for the entire state, the California Health and Welfare Agency obtained an injunction that, so far, has overruled the Plumas County action.

Meanwhile, however, a milder form of the protest has spread to other counties. At issue is the "Outreach" program, a Federally required plan for each county to advertise the availability of Food Stamps to ensure that everyone who is eligible in fact signs up. As of the end of summer, Plumas, Glenn, Lassen, and Tehama Counties had pulled out of or curtailed the program, and officials of Madera and El Dorado Counties were actively considering doing likewise. Since Food Stamps are an Agriculture Department program, the county officials believe they are not jeopardizing their HEW funds by this move. Nonetheless, the focus of the protest is clearly welfare programs as a whole. "The rising cost of welfare is inundating the entire nation," says Leonard Ross, Plumas County Supervisor. "We had to say 'no'; we can't keep giving away our national resources."

A similar protest is under way at the state level. Mario Obledo, California Secretary of Health and Welfare, has informed HEW that the state is refusing a Federal order to repeat an advertising program on the availability of social services. Obledo considers the advertising unnecessary and a waste of taxpayers' money, and noted that the state's refusal to comply could be the first time a court would have to decide whether the Federal government has "unlimited control over bureaucratic paperwork" requirements of state and local governments. By taking this stand, the state government risks losing $245 million in Federal welfare funds. Officials in Missouri are reportedly engaged in a similar protest.

SOURCES:

• "Plumas County Begins a Rebellion on Welfare," Los Angeles Times, Jun. 8, 1975.

• "More Counties Join Food Stamp Revolt," UPI (Sacramento), Aug. 21, 1975.

• "State Risks Loss of $245 Million by Opposing U.S.," AP (Sacramento), Aug. 13, 1975.

ANTITRUST RESTRAINED

The U.S. Supreme Court's first term of 1975 led to some major setbacks for the Justice Department's aggressive trustbusters, setbacks which indicate a halt to the expansion of this area of Federal regulation of business. A five-man majority has emerged—Burger, Powell, Rehnquist, White, and Blackmun—which is "not very sympathetic to the government's antitrust efforts," in the words of a Justice Department official.

Three of the most important cases this year have involved the scope of antitrust jurisdiction. In one (U.S. v. American Building Maintenance Industries), the Court ruled that the Clayton Act does not prohibit the acquisition of a company operating only within one state, even though the company deals with clients or suppliers active in interstate commerce. Another case (Gulf Oil v. Copp Paving) ruled similarly that the Robinson-Patman Act does not apply to transactions in which products don't cross state lines. Thus, of the three principal antitrust statutes, only the Sherman Act now considers "interstate commerce" to be virtually any sort of business, even one that is, in fact, purely local. Another merger case (U.S. v. Citizens & Southern) held that the government could not stop two companies from merging on grounds of "reduced competition" if there was no evidence that the companies had planned or intended to compete.

Two other landmark cases restricting the scope of the antitrust laws may prove a mixed blessing. In both (U.S. v. National Association of Securities Dealers and Gordon v. N.Y. Stock Exchange) the Court ruled that government regulation of an industry (in these cases, SEC regulation) precludes the application of the antitrust laws. Such rulings will hinder ongoing attempts by the Justice Department to break up government-fostered cartels in regulated industries.

In any event, the heyday that the anti-trusters enjoyed under the Warren Court has ended. No longer can the Federal government routinely expect to have its trustbusters upheld in the nation's highest court.

SOURCES:

• "U.S. Merger Controls Limited by Top Court," Los Angeles Times, Jun. 25, 1975.

• "The Court Turns Against Antitrust," Business Week, Jul. 14, 1975, p. 52.

AGAINST CONFINEMENT

A small but important step in the battle against involuntary commitment of people in mental institutions was taken late in June by the U.S. Supreme Court. In a unanimous decision, the Court held that self-sufficient mental patients who pose no danger to themselves or others can no longer be warehoused in state hospitals. Either they must receive treatment or they must be released. The decision was based firmly on "every man's constitutional right to liberty." In this case, that means that the mere fact that a doctor diagnoses someone as mentally ill "cannot justify a state's locking a person up against his will and keeping him indefinitely in simple custodial care."

Officials of state institutions had argued that they should be able to continue to confine such persons, because the state could often provide them with a better standard of living than they could manage on their own. But the Court replied, "The mere presence of mental illness does not disqualify a person from preferring his home to the comforts of an institution." Further, the state has no business locking up harmless eccentrics, ruled the court: "One might as well ask if the state, to avoid public unease, could incarcerate all who are physically unattractive.…Mere public intolerance or animosity cannot constitutionally justify the deprivation of a person's physical liberty." The decision's impact may be significant. According to the American Psychiatric Association, "at least 90 percent of those in state and county mental hospitals are not dangerous to themselves or others." Civil liberties lawyer Bruce J. Ennis, who argued the case, notes, "Most of them are just old. They are homeless, penniless, friendless, and maybe not too smart."

Significantly, the Court has only begun its work on the issues involved in mental illness cases. It has yet to decide the broader question of whether mental patients can be held against their will under any circumstances, even if treatment is provided, or if they are dangerous. So far, the court has simply taken an important first step.

SOURCES:

• "Free or Treat Harmless Mentally Ill, Court Rules," Los Angeles Times, Jun. 27, 1975.

• "Opening the Asylums," Time, Jul. 7, 1975.

COSTS OF LABOR MONOPOLIES

Federal legislation dating back to the Depression of the 1930's has had the effect of granting legal monopoly status to unions in countless instances. Several recent studies indicate the continuing costs of union monopolies, and a recent Supreme Court decision has made a small dent in these powers.

One such law is the 1931 Davis-Bacon Act, which requires construction workers on Federally-financed projects to be paid the highest prevailing union wage scale. A recent study of this law by Armand Thiebold of the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania concluded that the Act raises construction costs from $250 to $500 million over free market levels. When the secondary effects are included (e.g. the inclusion of Davis-Bacon provisions in 60 other laws and the upward bias given to private wage scales), the total impact may well be $1.5 billion per year. Sen. Paul Fannin has introduced legislation to repeal the Act in the current session of Congress, and repeal is being actively supported by the Associated Builders and Contractors (an association of open-shop contractors) and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

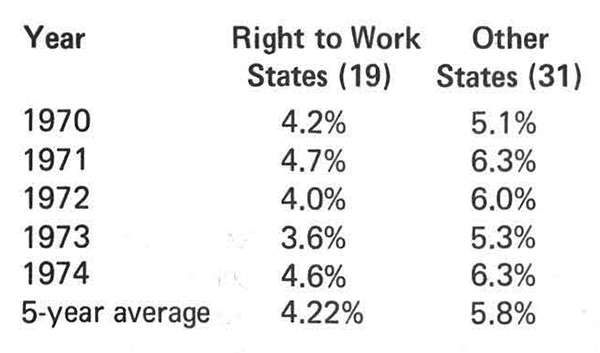

One reaction to such compulsory unionism laws as the Wagner Act was the passage in 19 states of "right to work" laws. While some advocates of the free market condemn these laws as further interference in the right of private parties to freely contract, others (including Nobel Prize winner F.A. Hayek) view them as a necessary corrective, given the existence of the Wagner Act. In any event, one important effect of right to work laws has been to promote a more competitive labor market, with the result that those states with right to work laws have significantly lower unemployment rates than states with monopoly unionism, as the following unemployment figures indicate:

Data such as these may eventually persuade union members and others who must work for a living to reconsider the benefits of Federal labor "protection."

Finally, raw union power has been dealt an important setback by the U.S. Supreme Court, which for the first time has held a labor union to be subject to the antitrust laws without having to be joined in conspiracy with a company. The case (Connell Construction Company v. Plumbers Local 100) involved the attempt by the union to convince nonunion Connell to sign an agreement to use only subcontractors having exclusive agreements with Local 100. To obtain compliance, the union shut down by picketing one of Connell's construction sites, even though it was not even attempting to organize Connell itself. The Court ruled that such an action was a restraint of trade, and that unions' exemption from the antitrust laws applies only to cases involving their own organizing—not attempts to pressure a contractor into choosing only union-organized subcontractors.

SOURCES:

• "Repeal of Davis-Bacon Being Sought in Congress," UPI (Washington), May 11, 1975.

• "Unemployment 50% Lower in Right to Work States," Right to Work News, Jul. 28, 1975.

• "High Court Applies Antitrust Laws to Big Labor," Human Events, Jul. 5, 1975.

MILESTONES

Religious Freedom. A Tennessee law requiring biology textbooks to give equal attention to all theories of the origin and creation of life has been ruled an unconstitutional violation of religious freedom, as guaranteed by the First Amendment. In separate cases both the State Supreme Court and the U.S. District Court voided the 1973 law. "Every religious sect, from the worshippers of Apollo to the followers of Zoroaster, has its belief or theory," wrote Federal Judge Frank Gray. "It is beyond the comprehension of this court how the legislature, if indeed it did, expected that all such theories could be included in any textbook of reasonable size." (Source: "Two Courts Void New Tennessee 'Monkey Law'," AP (Nashville), Aug. 21, 1975)

Money. Rep. Steve Symms has introduced a bill (H.R.8358) to provide for the minting of two new gold coins for sale to the public. The coins, to be known as the von Mises (one ounce) and the Jefferson (half ounce) would have no face value and would not be legal tender. Symms' proposal is essentially the plan proposed by Charles Curley in his article "A New U.S. Gold Coinage," in the June 1975 issue of REASON. (Source: H.R.8358, U.S. House of Representatives, Jun. 26, 1975)

Professions. Another blow has been struck against the monopoly status of the legal profession. A Los Angeles Superior Court judge has ruled that the state law prohibiting law firms from advertising is an unconstitutional infringement on freedom of speech. The suit was brought by the California Divorce League, an organization representing 50 legal clinics which assist people to obtain no-fault divorces. The clinics typically charge $65 to $100, compared with $250 to $750 from regular lawyers, and the suit alleged that the local Bar Association had prevailed upon the District Attorney's office to "put these clinics out of business because they threaten the income of the legal profession." The ruling resulted in the dropping of at least 28 misdemeanor charges against various clinics. (Source: "Do-It-Yourself Divorce Firms Win Ad Battle," Los Angeles Times, Jul. 25, 1975)

Drugs. A Federal judge in Oklahoma City has ruled that the FDA has no business preventing people from using the drug Laetrile, which supporters claim can prevent and/or cure cancer. Judge Luther Bohannon criticized the FDA for "abdicating its duty to the common man," and authorized a six-month supply for the plaintiff, Glen Rutherford. Mr. Rutherford, who had been diagnosed as having cancer in 1971, obtained Laetrile illegally before he went to Federal court and sued for an order prohibiting the government from interfering with his right to treat his body in his own way. (Source: "Cancer Drug Ruling Should Humble FDA," James Jackson Kilpatrick, syndicated column, Aug. 21, 1975)

Health Care. National Health Insurance (NHI) may be an idea whose time has passed, if current liberal sentiment can be believed. Both Sen. John Tunney and the Washington Post have recently come out against NHI as simply too costly, at least for the present. Tunney was formerly a cosponsor of Sen. Edward Kennedy's NHI bill, and the Post has long been a strong backer of nationalized medicine. (Source: "Tunney Opposes National Health Insurance," Los Angeles Times, Aug. 6, 1975, and "Post's Mortem on NHI," Private Practice, Aug. 1975, p. 3)