What You Should Know About Fiscal & Monetary Policy

Most investors understand that their gains and losses are determined (somehow) by government monetary and fiscal policies. The upturns and downturns in the market, or in the economy as a whole, are believed to be significantly influenced by loose or tight money, government spending, interest rates, and other factors which are under the control of the President or the Federal Reserve System. These are respectively the two high authorities which control fiscal policy and monetary policy. Since attempts to manage the economy by means of such policies have proven so unreliable in the past, this article will attempt to provide an overview from which the reader may start in order to formulate his own predictions about the economy.

Fiscal policy is formed initially by the Office of Management and Budget in Washington, directed by Roy Ash this year. With the formulation of the President's budget, the fiscal policy proposals are introduced in Congress. Fiscal policy may involve new taxes, or tax cuts, and government spending. After Congress authorizes a program, and appropriates money for the program (two separate steps), the policy—which by this time is plural—fiscal policies (also known as "pork barrel" legislation) are turned over to the bureaucrats for spending.

ENTER THE FED

Monetary policy is formed by the Federal Reserve Board in Washington. The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System are appointed by the President for fourteen year terms. The current Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board is Arthur F. Burns, formerly a professor of economics with a reputation for business cycle research. The terms of the members of the Board are staggered, so that a President will be able to appoint a majority of the Board only if he serves for two terms—and no President can appoint the entire Board. To the extent that monetary policy controls the upswings and downturns in the business cycle, each President must live with and suffer the blame for the monetary policy which the appointees of his predecessor decide upon. In theory the Fed is supposed to be above politics; in fact its policies have significantly moved the government in political directions (witness the Great Depression, and the changes in the role of government which that has led to).

Monetary policy is then executed by the Federal Open Market Committee, which buys and sells securities (usually in the New York market) and thereby makes changes in the money supply. When the Federal Reserve Bank of New York sells a government bond, it collects money; when it buys a bond, it disburses money. In our monetary system, money inside the Fed simply doesn't exist—it is created or destroyed as it is issued or collected. The money supply thus grows or shrinks, usually by a factor of 6 or 7 because each member bank can use the notes of the Federal Reserve Banks for fractional reserves.

Many people also believe that the Federal Reserve Board can influence fiscal policy by controlling interest rates. If the Fed can predict the demand for money, and control the supply of money, it can peg the rate of interest and thereby induce the private sector to spend or hold more money. The discount rate is often mistaken to be this "rate of interest." This theory is essentially a misleading notion—although it was followed by the Fed for several decades after the Great Depression. The reasons for this theory will become clear during our discussion, below, regarding the quantity theory of money and the autonomous expenditures theory of income.

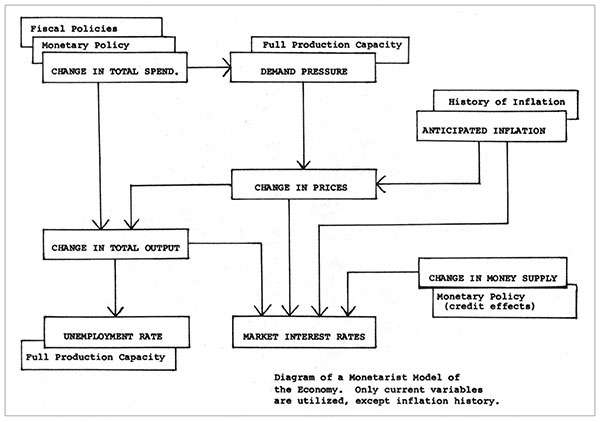

The fact about economics which makes understanding the system so difficult is the complex interrelationship of the various significant factors. Each of the quickly visible elements of the economic process will lead to less easily seen changes elsewhere in the market, and it is often difficult to estimate even the relative magnitudes or relative importance of the changes which are reported in the newspapers.

Government policies are considered to be important factors affecting the financial community because they are highly visible (except when the policymakers purposely prevaricate) and because unlike private market trends, they are usually more erratic—and hence introduce the destabilizing shocks which cause the business cycles.

GOVERNMENT'S ROLE

In the past decade, professional opinion among economists has been shifting more and more toward placing primary weight on policy changes by the government as a causal factor for the business cycle, specifically monetary policy, instead of looking upon government policies as a response to strange and unpredictable changes in the tastes of private consumers and investors. The publication in 1963 of an article by Milton Friedman and David Meisleman, entitled "The Relative Stability of Monetary Velocity and the Investment Multiplier in the United States, 1897-1958" marked the turning point, in this writer's opinion.[1] Significantly, two years earlier marked the ascendency in government circles of the so-called "New Economics" of the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations—to which the United States can credit the origins of its present problems with inflation.

The questions which every private citizen wants answered involve the direction of the economy. Private investment plans, not to mention planning for career opportunities or for retirement, all depend upon predicting the future, within broad categories. Individuals who are concerned with the financial markets on a daily basis are even more concerned with predicting the future as accurately as possible. One development in popular economic thinking is the fact that the soothsayers who rely on the monetarist models of the economy have a better track record than the prophets of the fiscalist school. Nothing will sell a theory more rapidly than the accuracy of its predictions—contrasted with errors on the part of competing theories. This has been the recent experience of monetary policy studies, compared with a less impressive record for fiscal policy analysts.

Yet, fiscal policy measures are popular and powerful factors in the American economy. More than a third of total spending is conducted within the government sector. Further, a government deficit which may be financed by selling bonds to the Federal Reserve System will expand the money supply and increase total spending simultaneously through monetary and fiscal policy. In fact, fiscal policy measures which draw funds exclusively from the private capital market will increase total spending to the extent of the government spending, but since private capital is siphoned off, the "multiplier effect" of fiscal policy approaches one for one. This is one reason why fiscal policy enthusiasts focus their attention on Federal government deficit spending and not on local or State government bond issues. Classical Keynesian theory argues that the multiplier effect should be the reciprocal of the average propensity to save (roughly three to one for temporary changes in real income). Economic stagnation is interpreted as the tendency of individuals to hold onto their savings longer than might be "socially desirable."

The creation of new money by the Federal Reserve System, however, does exert a positive and multiplied pressure on total spending because, given fractional reserve banking, one new Federal Reserve Note in a bank vault serves as the basis for loans which in total amount to 6 or 7 times the face value of the cash note. This is the distinction between "high-powered money" and ordinary checkbook money. The important question about a stimulative fiscal policy then becomes: How is the deficit spending to be financed?

Fiscal policy as a theoretical tool became popular during the 1930's because it characterizes the central government in an activist manner "doing something" to create jobs, and generally to put money in the hands of the public to spend. Obviously the government-spending part of the policy was immediately popular with politicians; but the other side of the policy, taxation to pay for government spending, has been much more difficult to manage. The economic theory which assumes that mysterious cosmic forces automatically lead to speed-ups and slow-downs in business activity then looks to an active, counter-cyclical government fiscal policy for stabilization—to run a budget surplus in times of full employment and to run a budget deficit in times of recession. The assumption is that people as a whole sit on large cash balances in times of recession, thereby causing a drop in total spending, and spend themselves into debt in times of full employment, thereby overheating the economy.

In point of fact, the stable factor in these relationships seems to be the amount of real wealth which people desire to hold in the form of cash balances—regardless of boom or bust in the business cycle. When the money supply expands, individuals observe an excess in their real cash balances (adjusted for the rate of inflation) and step up their spending plans. When the money supply stops expanding, or shrinks, individuals tend to slow down their spending plans to keep up their real cash reserves. The business cycle itself can be interpreted as the response of the economic system to the money supply "cycle" which has been managed rather badly by the Federal Reserve and the Treasury.

AUTONOMOUS EXPENDITURES

Behind the support for fiscal policy on the part of economists is the theory that income is determined by the level of autonomous expenditures, which include business investment decisions, home-building, and government expenditures. These are labeled as "autonomous" because they are not part of a formula dependent upon income, such as consumption and savings are assumed to be. The theory, usually identified with Keynes although it has gone through a number of variations, makes the assumption that there is a "leakage" in the cycle of income, consumption, savings, and investment (Say's law) because savers and those who spend investment funds to purchase labor services and capital goods are different individuals. Sometimes, for mysterious reasons (such as a lack of "business confidence") there is a shortfall in the amount of autonomous investment. In those cases, the theory argues, the government should make up the difference. Direct action by the central government is desired to make up for the lack of will on the part of the individuals in the market. In the 1929-32 period, of course, this "leakage" was the absolute contraction of the money supply caused by the Federal Reserve System. One third of all the money in circulation was removed, and the banking system collapsed.

So now the question becomes: Which theory is correct? The surprising answer is that both theories are versions of the same analytical system. Each theory, however, places emphasis on different variables, and each theory makes assumptions about which variables are stable, and which ones are controllable.

Fiscal policy assumes that the year to year ratio of savings and consumption is stable, whereas monetary policy assumes that the demand for real cash balances is stable. The economics profession fell into confusion when it was presented with two alternate theories of the same process, because nobody really knew which variables were more important. Largely on the basis of no evidence at all, the profession adopted the autonomous expenditures theory. The politicians were delighted to go along.

ENTER THE FACTS

In the past 10 years, at last, a significant amount of statistical research has uncovered the fact that the autonomous expenditures theory is less useful in explaining economic events than the quantity theory of money.

In other words, the simple version of the income-expenditures theory to which we have deliberately restricted ourselves in this paper is almost completely useless as a description of stable empirical relationships, as judged by six decades of experience in the United States. Though simple, this version is substantially the one that is presented in every recent elementary economics textbook as the central element in the theory of income determination. Such results as we have so far obtained from analyses for other countries strongly confirm results for the United States. On the evidence so far, the stock of money is unquestionably far more critical in interpreting movements in income than is autonomous expenditures. [p. 188, emphasis supplied]

If we can make the assumption that most businessmen and investors have learned their theories of economics from elementary textbooks on the subject, then we can point to an area for profitable investment of time and money. If most people believe a wrong idea, and act on it, then most people will be misled. The books listed at the end of this article for further reading should provide the reader with a comparative advantage in spotting upturns and downturns in the business cycle.

The reader should be warned, however, that we are discussing broad market concepts in a statistical context. The actual decisions which statistics summarize are made by acting individuals, and we cannot predict individual behavior except in very broad average terms. There is a variable lag between a visible movement in the rate of change in the quantity of money and a peak or trough in the market. Here again the more someone would study the relationships, the greater his comparative advantage would become. The monetary policy approach simply has a better track record for success than the fiscal policy approach.

In arguing for the greater usefulness of the monetary policy approach, Friedman and Meisleman conclude their article with an important distinction between a widespread belief in the "credit effects" of monetary policy as contrasted to the "quantity theory" approach. The mechanisms of the quantity theory approach have been described above, as they operate through the demand on the part of both households and business for real cash balances. The "credit effects" theory makes the assumption that monetary policy works primarily through the financial markets, affecting the rate of interest, and that the rate of interest then determines the magnitude of autonomous expenditures—which brings us to the same framework as the fiscal policy approach.

The mistake arises from a certain narrow perspective which the financial community automatically assumes. Since "the" rate of interest is important on a day-to-day basis, and since the activity of the Federal Reserve System has a strong effect on the yields of various widely traded securities, the short-term impact of monetary policy in the market will obscure a more accurate analysis of the long-term impact of monetary policy on the economy as a whole. The relevant interest rates which are influenced by a change in the quantity of money are not just those affecting business and the financial markets. The quantity theory of money treats "interest rates" as the abstract category which relates a periodic stream of payments or services to the economic value of the source of these payments or services, and not simply the rate on government bonds or commercial paper (pp. 213-222).

IMPLICATIONS FOR INVESTORS

In this article we have dealt very generally with the theories which underlie the fiscal policy vs. monetary policy analysis of the economy. There is an accelerating trend among investors and corporate treasurers to pay attention to changes in the money supply. We have not said anything about the motivations for changes in policy. Yet the real driving force behind the policies of the government is a fear of unemployment. Whether it is the spectre of the Great Depression, or some motive to help the poor, or just a prudent awareness that unemployed voters usually vote against the incumbent, Congress and the President are biased in favor of a rapid expansion of the money supply and increased Federal spending (financed by newly printed money, of course).

The attempt to "fight unemployment" by expanding the money supply, however, leads to an increase in demand pressure and to price increases. During the past four years one can see a very interesting pattern in the money supply: it was contracting until the Republicans took a beating in the 1970 elections, followed by a rapid turnaround in time for Nixon's re-election campaign in 1972. Our present inflation is a consequence of the rapid increases in the quantity of money during 1972 and early 1973. In mid-1973 the rate of change fell almost to zero—and now we have reports of growing unemployment, and an increase in Congressional restlessness. Since October (except for the month of January) the money supply has been growing rapidly again.

On the other hand, there is a strong consumer dissatisfaction with the present rate of inflation, and the only way to fight it is to squeeze the money supply. The schizophrenic attempts by the government over the next 10 years to prevent unemployment from rising during election years, and to prevent inflation from reaching levels of 15 and 25 percent (a very real possibility) will produce a series of business cycles which may prove very profitable to the investor who knows what to look for on the financial pages, or who knows which economists and other soothsayers are on the right track. In this brief article, we have only touched on some of the more distinct differences between monetary policy and fiscal policy. The reader will have to go to the primary sources for the really useful knowledge, in order to predict the future according to his own judgment—and to get that confident feeling that he will be right more than half the time.

J.M. Cobb is employed as the Chief Budget and Fiscal Officer of the Industrial Commission of Illinois. He has published a number of articles on economic topics since graduating from the University of Chicago in 1966.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

[1] The Friedman and Meisleman article appears in Commission on Money and Credit, STABILIZATION POLICIES (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall 1963), pp. 165-268. Subsequent parenthetical page references are to this article.

The reader is directed to the following books for further study:

Milton Friedman, THE OPTIMUM QUANTITY OF MONEY AND OTHER ESSAYS (Chicago: Aldine Publishing Co. 1969). For those with a taste for economic theory at the advanced level.

A. James Meigs, MONEY MATTERS (New York: Harper & Row 1972). A highly readable discussion of monetarist vs. fiscalist theory, complete with an economic history of the last 10 years.

Beryl W. Sprinkel, MONEY AND MARKETS, A MONETARIST VIEW (Homewood: Richard D. Irwin 1971). An excellent "how to do it" book for the investor who wants economics explained to him.

Everyone should immediately write to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis to request placement on the mailing list to receive (free of charge) their weekly "U.S. Financial Data," a compilation of graphs and charts of money supply and interest rates.