Rise of the Hipster Capitalist

Selling out? For millennial butchers, bakers, and candlestick makers, that's the whole point.

Popular wisdom about millennials seems to come in two varieties: They are either an entitled, narcissistic group of basement-dwellers, gazing at their selfies while the world burns, or they're a perfectly upstanding young cohort who got a raw deal from the recession economy. Millennials make awful employees because their boomer parents gave them too many soccer trophies; or maybe they can't find jobs because those same boomer parents aren't exiting the workforce. The one thing everyone can agree on is that millennials are probably screwed.

If there is a single cultural avatar that has come to represent today's young adults, it's the hipster, a much debated and often reviled construction built on skinny jeans, music snobbery, and urban chicken coops. You can find them tending their beehives atop graffiti-covered warehouses in Brooklyn; opening craft breweries and Korean-taco food trucks in Portland; or ditching the cities to get back to the land-in a farmhouse with high-speed Internet service, six laptops, three iPhones, and a heavy-duty Vitamix blender.

The hipster mixes hippie ethics and yuppie consumer preferences, communal attitudes and capitalist practices. Unlike prior generational stand-ins-from flappers to beats, punks to slackers-hipsters aren't rebelling against their parents or prior generations; they're mixing and matching the best of what came before and abandoning the baggage that doesn't interest them.

The hipster ideal today is neither a commune nor a life of rugged individualism. It's the small, socially conscious business. Millennials are obliterating divisions between corporate and bohemian values, between old and new employment models-they're not the first to do this, but they are doing it in their own way. Armed with ample self-confidence but hobbled by stagnant prospects, millennials may be uniquely poised to excel in an evolving economy where the freelance countercultural capitalist becomes the new gold standard.

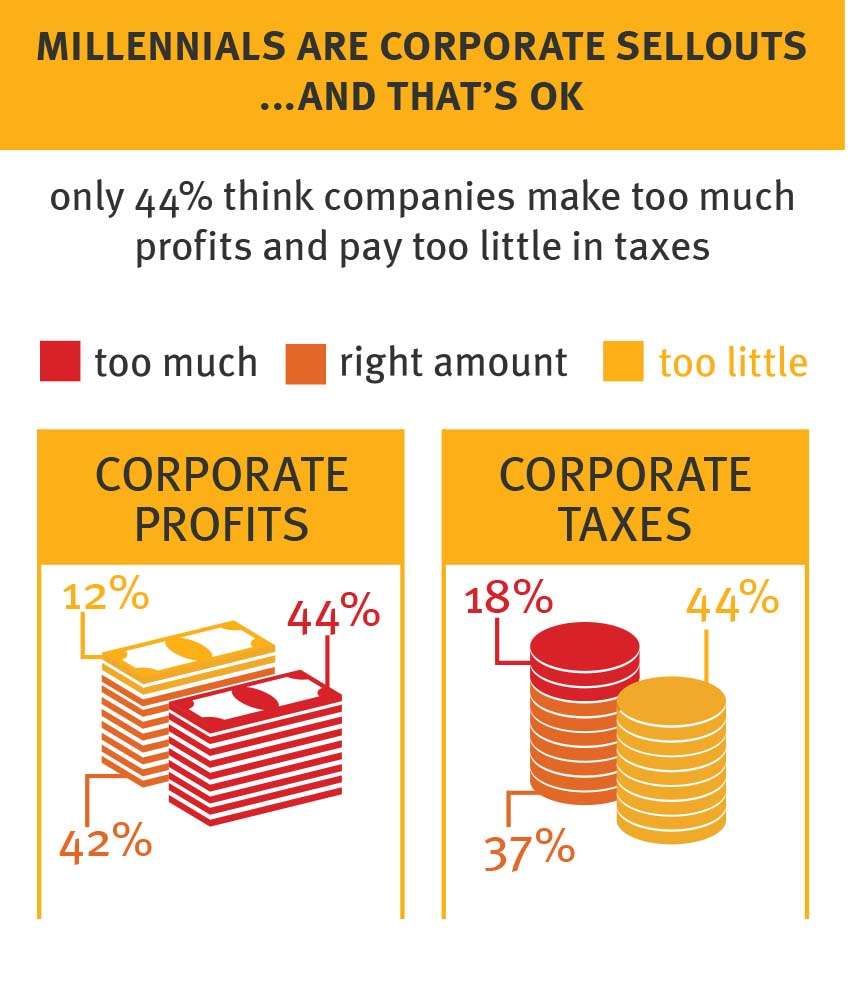

"I think people used to be very wary of business, and still maybe are wary of business," says 26-year-old Mark Spera, who quit a corporate job with the Gap to launch an eco-friendly fashion company called BeGood Clothing with his college roommate. "But profit isn't seen as such an evil thing anymore. It's more about how that profit is used."

Beyond 'Selling Out'

In the '90s musical Rent, a Disneyfied depiction of Gen X bohemians, a group of aimless artist/rebels coalesce around the AIDS crisis, a shared passion for "hating dear old Mom and Dad," and their widely held generational opposition to "selling out." From riot grrrl 'zine publishers to Nirvana's Kurt Cobain, anxiety over selling out to the mainstream dominated the cultural discourse of people who came of age in the '80s and '90s. Baked into the concern was an intrinsic sense that art and social change could only be corrupted by capitalism.

Millennials, generally considered to be those in the late teens to early 30s right now, simply do not wrestle with this issue. "Hipsters may be stylistically similar to earlier youth movements," wrote The New Criterion's James Panero in a 2012 New York Daily News story. But "they strip away the anti-social and anti-capitalist qualities of these groups and replace them with entrepreneurial drive."

William Deresiewicz, a Yale English professor turned Portland-based author and cultural critic, argues that the whole idea of a hipster "movement" is absurd, because modern youth culture lacks elements of radical dissent or rebellion. "The hipster world critique is limited. It's basically a way of taking the world we have now and tweaking it to make it better," he says. David Brooks' 2000 book Bobos in Paradise argued that two formerly distinct baby boomer classes-the hedonistic, artistic, and socially tolerant bohemians; and the conforming, capitalist bourgeoisie-had combined to form a new category he christened bobos. Hipsters, Deresiewicz argues, are the bobos' literal and metaphorical children.

"I suspect that a lot of these hipsters are going to be bobos in 20 years," he says. "There's a symbiosis." Hipsters make and popularize the things, material and cultural, that bobos consume-from nitrate-free salami to the indie bands that make it into Rolling Stone.

"Millennials and boomers don't recognize how much they're like each other," he says, but this generation has "absorbed the values of the boomers. " In a 2011 New York Times essay, Deresiewicz dubbed millennials "Generation Sell."

Much of this entrepreneurial spirit is born out of necessity. Older millennials were just entering the work force at the start of the Great Recession, and many lost their jobs or graduated from college with massive amounts of debt in a historically weak job market. As of spring 2014, the unemployment rate for 18- to 29-year-olds was still hovering around 16 percent, and millennials made up 40 percent of all unemployed Americans.

For those millennials who do have jobs, wages have stagnated or dropped. Since 2007, real wages have dropped 9.8 percent for high school graduates and 6.9 percent for young college graduates, according to data from the Economic Policy Institute. These trends predate the financial crisis: Since 2000, wages for high school graduates have declined 10.8 percent, and the wages of young college graduates have decreased 7.7 percent. (Compare that to Gen Xers from 1995 to 2000, when wages for young adults rose between 15 and 20 percent.)

Millennials have adjusted their expectations accordingly. Job security and retirement benefits seem as quaint and anachronistic as floppy disks and fax machines. And only 6 percent of millennials think full Social Security benefits will be available to them, according to a Pew Research poll from March 2014, compared to 51 percent who think they'll get nothing.

Yet members of Generation Y, as millennials were once known, are still remarkably optimistic about controlling their own destinies, despite the mess of 21st century America. Pew found that nearly half of millennials think the country's best years are ahead, and a majority expect to have enough money to lead the lives they wish. The recent Reason-Rupe poll of millennials found the three biggest factors they believe determine career and financial success are hard work, ambition, and self-discipline (followed by natural intelligence or talent, family connections, and a college degree). What do they think is the most important factor producing poverty? Poor personal decisions.

The very things seen as most portending of millennial doom-their overinflated sense of self-esteem and the stagnant economy-may have, when taken together, inspired a new paradigm. For millennials, when life gives you lemons, you make artisanal, small-batch beef jerky. Or start a cargo-bike delivery service. A yoga studio. A craft brewery. A combo cocktail and pie bar. An app-based laundry pickup service. Depending on which survey you consult, 30 to 80 percent of millennials aim to be self-employed at some point in their careers.

In the Reason-Rupe poll, 55 percent of millennials said they would like to own their own company someday. A 2011 poll from the Kauffman Foundation found that 54 percent of millennials had entrepreneurial ambitions, with higher levels among Latinos (64 percent) and blacks (63 percent). Sixty-five percent said that making it easier to start a business should be a priority for Congress.

More than a quarter of Gen Y is currently self-employed, according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation. In 2011, nearly a third of all entrepreneurs were between the ages of 20 and 34. Millennials are also on the cutting edge of workplace flexibility. A 2011 poll from Buzz Marketing Group and the Young Entrepreneurs Council found that 46 percent of the cohort had done freelance work.

When people think of millennial entrepreneurs, their minds tend to go to tech giants like Facebook co-founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg. Indeed, many of the most popular tech and social media startups of the past half-decade have been founded by young people, including Tumblr, Vimeo, Instagram, Dropbox, Lyft, Living Social, and AirBnB. But other sectors are benefiting from youthful creativity as well.

Millennial entrepreneurs are embracing publishing, from reimagined service-journalism (think Ezra Klein's Vox) to SEO-driven websites (Brian Goldberg's Bleacher Report and Bustle), publications directly targeting teens and 20-somethings (millennial news site Mic, Alexa von Tobel's Learn Vest, Tavi Gevinson's Rookie), and "small batch" niche magazines like the aspirational dinner party pub Kinfolk. They're founding socially conscious clothing companies such as BeGood (a San Francisco-based retailer that sells moderately priced, eco-friendly fashions such as bamboo tank tops and organic-cotton T-shirts) and Five Pound Apparel (which donates five pounds of food to Nepalese children for every T-shirt sold). And they're all over the craft alcohol and specialty food markets.

"Entrepreneurship has become the creative endeavor," says Deresiewicz. "It's not just a business endeavor. And even when you're engaged in a creative endeavor like music, it becomes sort of framed like an entrepreneurial act." In fact, "'selling out' as a category has disappeared, because everybody is selling out," he adds. "We're all inside the market system now."

Brooklyn Capitalism

Far from being a no-fly zone, cashing in is now the goal for many millennials. Molly Brolin, 26, is an "artist entrepreneur" who runs a small company, Muddy Boots Productions, from her living room in the hipster haven of Greenpoint, Brooklyn. When I lived across the street, in 2009 and 2010, I remember Molly-then a recent college graduate-having boundless enthusiasm for taking on new, unpaid creative work. "I used to do whatever inspired me," says Brolin. "But now I'm more thinking about 'how is this going to make us money?' I feel like reality is really setting in right now. I can't keep doing things just for experience."

In another part of Brooklyn-Bushwick-I once lived in a warehouse that had been converted into a semi-legal residential space, populated largely by painters. My dozen or so roommates, which also included a D.J., a puppeteer/performance artist, an aspiring comedian, and an unemployed schizophrenic, were mostly in their twenties, socially liberal, ambitious, and poor. Our living space was rustic, with heat and Internet that frequently went out. (Guess which failure provoked more panic?) An area of the fridge was devoted to communal, dumpster-dived foods.

At one point, the painters decided we should use the front of the warehouse-which housed a skate ramp and a small purple school bus that served as a bedroom-to exhibit their paintings. Young, non-established artists have long used whatever space is available to them to showcase their work. But my roommates' planning from the get-go involved not merely showcasing their art for the local creative community but luring in wealthy buyers. They were dying to sell out.

"Ultimately, money is power, and if you have more power you can use that power for good things," says David Simnick, CEO and co-founder of SoapBox Soaps, which donates a bar of soap or a portion of proceeds to charity for every soap and body wash it sells.

But economic necessity is also at play. The concurrent rise in cultural capital and cost-of-living expenses in a handful of prominent U.S. metropolitan areas make them both vital and almost prohibitively expensive for young creative types. Tiny, lofted bedrooms in the aforementioned warehouse were still renting for $450 to $600 per month, plus utilities. Selling out means making rent.

In the Buzz Marketing Group/Young Entrepreneurs Council survey, 33 percent of the 18- to 29-year-old respondents had a side business. (This included activities like tutoring and selling stuff on eBay.) Platforms such as Etsy, an online emporium for handmade goods, and the ridesharing service Uber put self-employment, of a sort, within millions of millennials' reach. Much is made of how the new "sharing economy" disrupts old business models and empowers consumers, but these businesses have a transformative effect for workers, too.

Take Bellhops, a small-scale moving company founded by two college students in 2011. Bellhops now employs more than 8,000 part-time workers across 42 states. These student movers control their own jobs, choosing not just when and how much they work, but whether they want to take a "captain" or "wingman" role on a particular job.

Bellhops COO Matt Patterson told Forbes his motto is "Bellhops are entrepreneurs in their own rights." He's not exactly wrong: In a recent survey, 90 percent of working professionals defined being "an entrepreneur" as a mind-set, not just "someone who starts a company." In the new lexicon, Bellhops, Uber drivers, and AirBnB hosts are all entrepreneurs.

The flexibility and autonomy that comes with this small-scale entrepreneurship is ideal for millennials, who in survey after survey list these attributes among their most-wanted from employers. Millennials are loathe to accept rigid work arrangements or stay at jobs they don't enjoy. "Our generation feels super entitled to live the way we want," says Brolin. She thinks "the American Dream has morphed," from the steady, practical careers of earlier generations to "making businesses as artists and creators." Because millennials are mostly unmarried and not tied to property, they're more willing to take risks to find a way to make a living that also inspires them creatively or creates some sort of social good.

"When my parents were growing up, providing came before playing," says Christopher "Tinypants" Dang, a 31-year-old designer whose latest clothing line is called As We Are. For Dang and his colleagues at Live Love Collective—a "lifestyle marketing agency" with the motto "Have Fun. Do Good. Live Love."—"money is part of the picture," but so is "excitement, awareness, responsibility and community," Dang says. The young entrepreneurs I talked to for this story kept coming back to the same narrative: They had launched businesses after becoming disillusioned by the corporate culture or lack of autonomy at a traditional job. Kalysa Alaniz-Martin, 26, opened her own hair salon in 2012 after working at several chain salons and disagreeing with their practices. At Kayos Studio in Lafayette, Indiana, Alaniz-Martin uses only ammonia-free and vegan hair care products and tries to be environmentally responsible in her product choices and water use.

(Article continues below)

BeGood co-founder Mark Spera was burned out on his corporate job at the Gap. "I couldn't imagine the idea of sitting at a desk all day, not having some autonomy over my workload," says Spera, who recalls being shocked when a vice president at the company scolded him for sitting barefoot at his desk. He and his business partner "were both sick of what we were doing and wanted to do something more impactful. I was considering getting into a nonprofit and he was considering traveling abroad."

Young do-gooders of generations past might have gone into the nonprofit world or the Peace Corps. Today, by contrast, many see themselves as able to do the most good via for-profit, socially conscious businesses. They do not see any inherent contradictions in that approach.

"You talk to people in the nonprofit world who say, 'You guys are doing a great thing, but why don't you donate all your money?'" says Spera, laughing. "Because then we'd be a nonprofit!" And BeGood is not a nonprofit. It's an example of a new dream, dubbed social entrepreneurship.

There are now at least 30 programs in social entrepreneurship at U.S. colleges and universities, according to Harvard Business School blogger Lara Galinsky; a decade ago, there were none. Forbes recently published its third annual list of "30 Under 30 Social Entrepreneurs." It included people like 28-year-old Joel Jackson, founder of Mobius Motors, which is making inexpensive SUVs to sell in Africa; and Kavita Shukla, the 29-year-old inventor of a cheap, compostable paper infused with organic spices that keeps produce fresh longer and ships to 35 countries.

Conscious Consumerism

Some social entrepreneurs-like Spera, a 2010 graduate of the University of Richmond's business school-come out of traditional undergraduate business or MBA programs. Many more have taken a more oblique path, turning hobbies like baking and gardening into full-time endeavors after corporate life proved unpalatable.

When her career in art administration proved unfulfilling, Allison Kave started selling pies at local food markets for extra cash and "creative satisfaction." When the pies proved a hit, she quit her art-world job and started selling them full time, supplementing her income with cooking classes and a bartending gig. Now Kave has a cookbook under her belt (First Prize Pies, 2014), and is working with friend Keavy Blueher to open a joint dessert and cocktail bar in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, called Butter & Scotch.

"A lot of my colleagues in the food world seem to have come to their businesses from previously established careers that were lucrative but not rewarding," says Kave, contrasting these entrepreneurs with previous generations. "They chose to take huge pay cuts to pursue their dreams and make a business out of their passions. I think about my grandfather, who owned Pepsi routes around Brooklyn, and his inclination toward self-employment seemed more driven by necessity than a particular love of carbonated beverages."

Consumer choices were also less value-laden then, but we're now squarely in the age of "conscious consumerism." Any social entrepreneurs worth their (fair-trade, alder-smoked) sea salt will have an "our story" section on their website, explaining how a college trip to Guatemala or a grandmother's devotion to fresh produce inspired the company's current mission. "It's not just 'my candles are great', it's 'and then I went to Java and discovered this wax and this is a part of my journey, here's a picture,'" says Deresiewicz. "Goods now all have to be experiences."

BeGood founder Spera says conscious consumerism is what makes companies like his possible. "You have access to so much information now that companies that aren't doing the right things are going to get killed by companies who are."

America's appetite for organic, artisanal, locally sourced foodstuffs has put the gun in hipster entrepreneurs' hands. Critic and editor James Panero has called hipsters New York's "most active innovators." As traditional manufacturing has left Brooklyn and Queens, hipsters have taken up the slack.

In a few short years, an array of Brooklyn companies founded by millennials have gone from passion projects to national powerhouses. Erica Shea, 29, and Stephen Valand, 28, quit their jobs in 2009 to start Brooklyn Brew Shop, a line of easy-to-brew beer kits designed for kitchen stove tops. They are now sold in over 2,500 retailers globally. In 2010, Kings County Distillery was founded by two millennials who use local grain and traditional distilling methods to make small-batch spirits; the duo have won multiple craft distiller awards and distribute regionally and in California. Laena McCarthy started selling Anarchy in a Jar jam at indie food markets in 2009, and now makes handmade, all-natural jams, marmalades, chutneys, and mustards for stores from Portland, Maine, to San Francisco. The Brooklyn Salsa Company started as an underground taco delivery service run from a Bushwick loft and now sells locally sourced, direct-trade organic salsas around the country.

"In post-industrial capitalist society, 'work' has come to be disconnected from any conception of directly producing something or contributing work with any specific content," the socialist mag Jacobin complained recently. But for hipster entrepreneurs, this couldn't be further from the truth. Adam Davidson, co-founder of NPR's Planet Money, asserts that hipsters are classical capitalists in the Adam Smith model.

Today's niche startups and craft businesses aren't a rejection of modern industrial capitalism, Davidson wrote in a New York Times piece titled "Don't Mock the Artisanal-Pickle Makers." Rather they're "something new" entirely, "a happy refinement of the excesses of the industrial era plus a return to the vision laid out" by Smith. They also highlight a potential bright spot in U.S. manufacturing: small American producers succeeding by avoiding direct competition with cheap commodities from low-wage countries and instead providing hyper-specialized technological and lifestyle products. Perhaps "the fracturing of the manufacturing industry, however painful, has helped prepare parts of the economy for this new course," Davidson suggested.

"If hipsters are to evolve into anything meaningful, they will adhere to no historical pattern," journalist Ilie Mitaru predicted in Adbusters back in 2009. "Every journalist, politician, and organizer works with an assumed vision of our sociopolitical future—be it partisan reform, fringe uprising or global revolution. This vision blinds us to the potentiality of it happening another way, one with no historical precedent."

As we enter the post-crisis period, the business and economic contexts we knew pre-recession are increasingly unlikely to re-materialize. In their willingness to embrace new ideas and new work models, millennials may turn out to be revolutionary in ways altogether different from generations past.