Generation Independent

Millennials aren't listening to you. That's a good thing.

There was a moment at the 2013 Grammy Awards that captured how millennials are different than Gen Xers and baby boomers, and what it all means for the future of America. After the traditional parade of side-boob-flashing songstresses and tonsorially wackadoo manchildren allegedly flouting convention in utterly predictable ways, the hipster band fun. (whose name is uncapitalized and over-punctuated) was honored with a richly deserved statuette for the catchy generational anthem "We Are Young."

The song broke big after being featured on the hit series Glee, itself a touchstone of the millennial generation, roughly defined as those born between the beginning of the 1980s and the early '00s. Glee is set in the sort of high school unimaginable to Americans raised on older coming-of-age fare such as Happy Days, Rock and Roll High School, or even the ultra-G-rated Saved by the Bell. On Glee, even (especially!) the football players sing in a music club that features a paraplegic guitarist, a Down Syndrome cheerleader, and a lesbian Latina, an ensemble that would have been a punchline just a few decades ago. (As recently as 1983, U.S. Interior Secretary James Watt made headlines for joking that an advisory panel he appointed consisted of "a black, a woman, two Jews, and a cripple," a comment that led to his resignation.)

"We Are Young" is a smart variation on that enduring theme of pop music, the booty call. "We are young," croons the singer to a lost or near-lost love, "So let's set the world on fire/We can burn brighter/than the sun." But then comes the generational twist: After vaguely alluding to "scarring" his lover through some unspecified failure, the protagonist sings: "If by the time the bar closes/And you feel like falling down/I'll carry you home./I know that I'm not/All that you got."

What matter of musical strangeness is this, actually acknowledging that your drunken, staggering bedmate could do better than you? "We Are Young" is a song in which the singer is a decent human being and penitent lover, an emotional designated driver rather than the standard-issue letch that has dominated the charts from your grandparents' "Baby It's Cold Outside" to your parents' "Under My Thumb" to the entire hair-metal genre of the '80s.

The 2013 Grammys, in contrast, were a millennial coming-out party for a different kind of POV. The post-racial, post-ethnic, post-American, post-heteronormative, post-everything likes of Rihanna and Bruno Mars and Frank Ocean and Janelle Monae and Skrillex took center stage, and the winningly metrosexual fun took home top honors for its kinder, gentler love song.

Then came the real intergenerational shocker, when one of the members of the group thanked his parents for letting him live at home "for a very long time." Did Mick Jagger even have parents? Would Axl Rose have been able to pronounce the word mother, let alone thank her for letting him couch-surf? You could feel a half-century of rebellious rockers, from Jim Morrison to Joey Ramone, groaning in their graves.

Millennials, like F. Scott Fitzgerald's rich, are different than you and me. For one thing, at around 80 million strong, they're as big as or bigger than the baby boom—and far more populous than both Gen X (born between 1965 and 1980) and the Silent Generation (1929-1945). They are filled with what at first glance looks like contradictions: More Democratic in their voting behavior than previous generations, and yet more politically independent than any cohort in history. Worryingly unafraid of the word socialism, and yet full-bore in favor of the free market.

Understanding what millennials care about, what they believe in, and how they think is a first-order priority of anyone interested in the future of American politics, culture, and ideas. To that end, earlier this spring the Reason Foundation, with the support of the Arthur N. Rupe Foundation, conducted a national poll of nearly 2,400 18- to 29-year-olds to get a better read on this confounding cohort. Among the most important takeaways: Millennials view cultural issues as central to their identities, and they speak a distinctly different language from the tired utterances of their elders.

The Unclaimed Generation

In 2008, Barack Obama pulled an amazing 66 percent of the youth vote while his weather-beaten Republican opponent, John McCain, managed a measly 32 percent. As recently as 2000, the youth vote had been split evenly between George W. Bush and Al Gore, with each pulling slightly less than half the total. (The rest went to third-party candidates.) Democrats look at such trends and declare future elections over before they've started. And on a superficial level, why not? According to the Reason-Rupe poll, twice as many millennials—43 percent—call themselves Democrats or lean that way than call themselves or lean toward Republicans.

Yet the most notable thing about millennials is not their devotion to the party of Harry Reid and Nancy Pelosi but their political disaffiliation from both major political tribes. Fully 34 percent of 18- to 29-year-olds describe themselves as independent, compared to just 11 percent of voters 30 years and older. That's a massive difference, indicating both a healthy skepticism toward the claims of professional politics and an openness to new arguments that align with their values. The country as a whole has been trending more independent, but millennials are the trailblazers in the non-aligned movement.

Who can blame them for that? This is a generation raised on the Internet's horn of plenty, 150 cable channels plus video-on-demand, 50 ways to classify your sexual identity on Facebook, and a heck of a lot more than 31 flavors of ice cream. How can just two measly political choices, whose origins predate the Civil War, win millennials' fickle brand loyalty?

The ideologically incoherent collections of historically tethered interest groups and ideas in each of the two major parties just does not make sense to your rank-and-file 25-year-old. For decades now, Republicans and Democrats have pretended that there is some obvious and necessary connection between your positions on corporate income tax rates and immigration reform, on unions and abortion.

Millennials? They are far more likely to be socially tolerant (something that fits with the Democrats) and fiscally responsible (a perennial Republican talking point). Most millennials—53 percent—say they would support a candidate who is both socially liberal and fiscally conservative. Good luck finding one.

Furthering this alienation, both parties on the millennials' watch have taken turns wielding power and failing utterly to live up to their professed ideals. The Republicans' alleged fiscal responsibility turned into fiscal incontinence under George W. Bush and a GOP-dominated Capitol Hill, and Obama's civil libertarian campaign promises turned into a dramatic ratcheting-up of the executive branch's ability to spy on and even assassinate U.S. citizens.

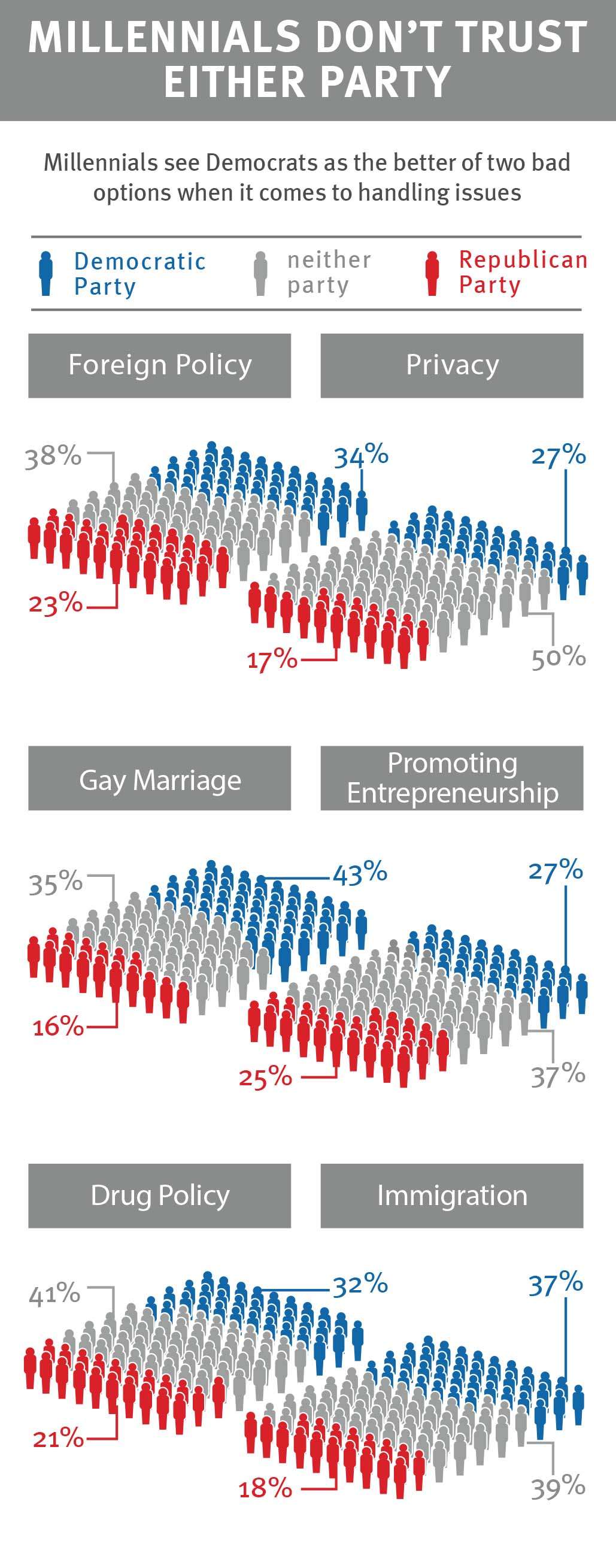

The Democrats and Republicans' inability to either deliver on their promises or stray from their tattered ideological scripts helps explain why millennials place such little faith in either parties or politics. Asked which party they trust to better handle a wide variety of issues, including education, drug policy, promoting entrepreneurship, foreign policy, and the environment, millennials consistently vote "no confidence." When it comes to protecting privacy, for instance, only 27 percent trust the Democrats to do a good job and just 17 percent pick the Republicans; fully half said neither party was up to the task.

(Article continues below)

So yes, the initial millennial enthusiasm for Barack Obama was historic, but that shouldn't be confused for a permanent alignment with the Democratic Party. Even in 2012, millennial support for the president's re-election shrunk by six percentage points, with voter turnout considerably lower-and that was before whistleblower Edward Snowden's revelations laid a direct hit on Obama's poll numbers among the young. What will happen in 2016 if the GOP fields a candidate who is younger than the Democratic nominee, and perhaps even more aligned with millennials' civil libertarian concerns?

Political scientists and sociologists have long recognized that people's ideology and voting patterns tend to get baked in during their twenties. As Penn State developmental psychologist Constance Flanagan has written, youth is "a politically definitive time" and forming an "ideology enables youth to organize and manage the vast array of choices the world presents." Most people's voting patterns and ideological orientation are a continuation of and reaction to what their parents believed and discussed around the kitchen table, memorable events such as wars and inventions, and both short- and long-term economic realities. Things typically gel in the late twenties or early thirties, and the final product tends to remain stable for the next several decades.

Millennials' cultural memory begins with the nightmare of the 9/11 attacks, and their entire politically aware lives have been marked by constant war and economic stagnation. The long-term, slow-moving failures of nation-building in Afghanistan and Iraq and of massive stimulus spending (first under Bush in 2008, then Obama in 2009 and 2010) cast a long shadow over the efficacy of broad-based government intervention into foreign and domestic affairs. Millennials' job prospects have been smothered first by the financial crisis and then by the painfully, historically slow rebound from the Great Recession. All this at a time when student loan debt has skyrocketed.

Exactly where millennials might end up in terms of conventional political affiliation or ideology is anyone's guess. But it's clear that neither party has come close to winning them over. Politically, millennials are the unclaimed generation. And they'll stay that way until a party consistently puts together candidates and platforms that reflect their values rather than those of their parents.

Culture First, Politics Second

Being politically independent isn't the same thing as being undecided or uncertain. Gay marriage, for instance, is a settled issue for 18- to 29-year-olds, with 67 percent supporting legal recognition for same-sex couples. No candidate at any level is ever going to win the millennial vote by defining marriage as only existing between one man and one woman. Even 54 percent of Republican millennials support gay marriage. What boomers and Gen Xers agonized over for a generation—from Ellen DeGeneres coming out to the controversy over the children's book Heather Has Two Mommies to Barack Obama's suspiciously timed change of heart on the issue in 2012—doesn't even register for millennials as a topic up for debate.

Pot legalization is also a done deal for millennials, with 57 percent in favor of treating weed like beer and wine. Similar or even larger majorities call for other individual freedoms: lowering the drinking age, legalizing online gambling, letting people smoke e-cigarettes in public. Despite being raised by helicopter parents and spending far more time in institutional settings, from day care through college, millennials are desperate to take off the bike helmets and engage the world free of their elders' literal and metaphorical safety equipment.

While large numbers of millennials care about government spending and the national debt—78 percent agree that both are a major problem—such values do not define their politics. Indeed, over two-thirds of millennials who describe themselves as liberal do so because of social and cultural issues, not economic ones. It's about gay marriage and pot legalization, not farm subsidies and food stamps. This is huge and demands attention.

Among Americans over 30, nearly half of voters lean Democrat and 40 percent lean Republican. Among millennials, the Dems' narrow lead over the GOP becomes a rout: 43 percent to 22 percent. Without question, this gap is largely attributable to social issues. But partisans on the left are constantly massaging the numbers to indicate an innate generational love for big government that just isn't there.

In a 2013 poll, for example, Pew Research Center found that millennials were the only cohort to support a "bigger government [and] more services," by a spread of 53 percent to 38 percent. Members of the Silent Generation, baby boomers, and Gen Xers all decidedly preferred "smaller government [and] fewer services." That finding, along with massive (if declining) support for Obama, was enough for some politicos to declare permanent victory. "These results," according to Government Executive magazine, mean that "even if most young Americans aren't willing to identify with the Democrats, they will still likely stick with them at the ballot box when presented with a Republican alternative."

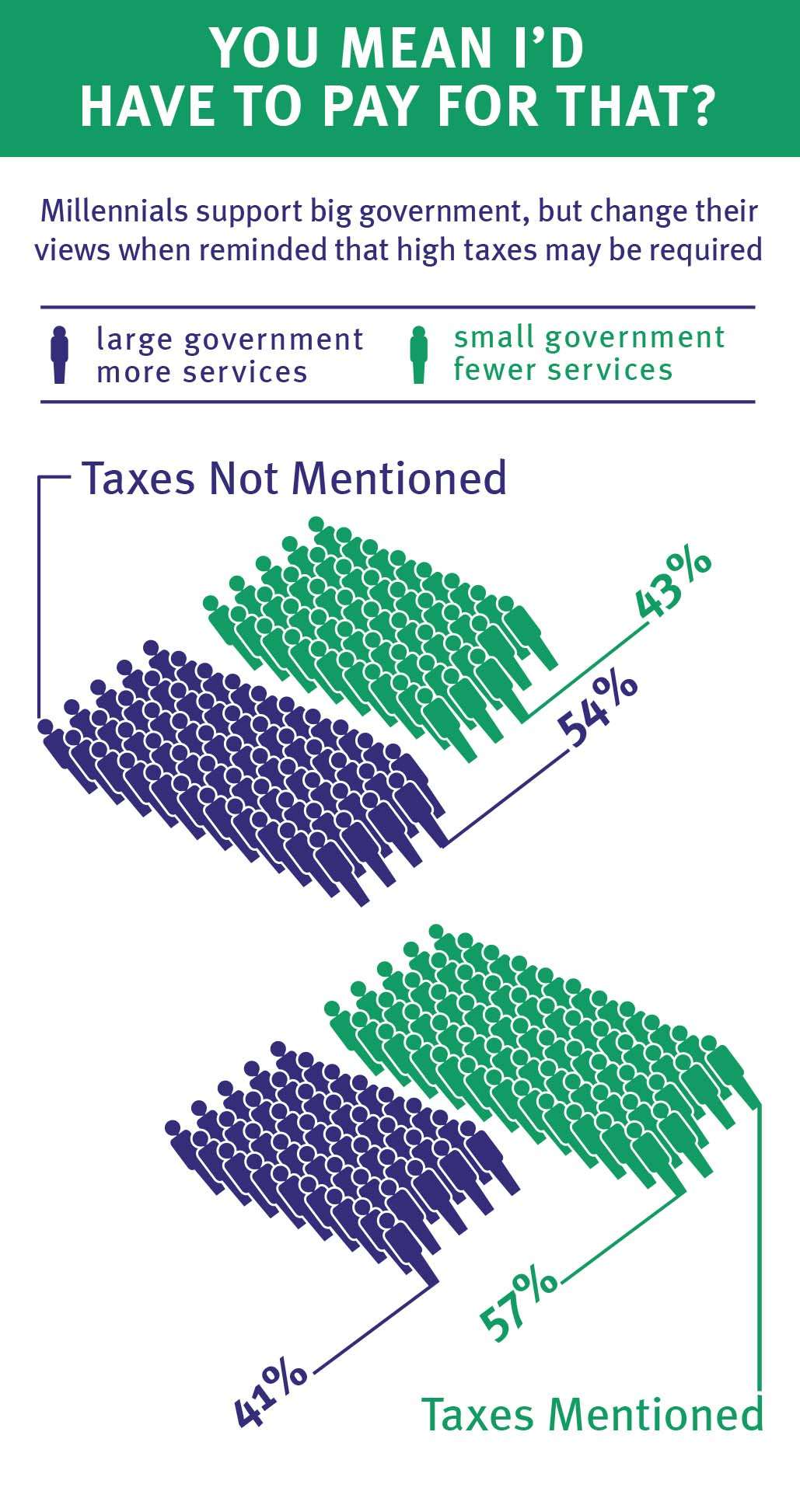

The truth is more complex. The Reason-Rupe poll replicated Pew's response when asking millennials if they would rather have a government that provided more services or fewer services: Fifty-four percent chose bigger government, with just 44 percent calling for a smaller government offering less services.

But when the same question is asked in the context of paying higher taxes for more government services, the results flip. Asked if they would prefer a "larger government with more services" that would require high taxes, just 41 percent of millennials want the larger government, with 57 percent preferring a smaller government and low taxes. This preference generally extends across income and ethnic groups; it's a generational attribute.

(Article continues below)

Support for "big government" ideas also begins dropping as millennials begin working and living on their own. But at the same time, it's clear that this generation is not exactly agitating for the government to be drowned in a bathtub. Getting at millennials' precise attitudes toward the size and scope of government requires hacking through some significant linguistic misunderstanding.

The New Generation Gap

During the late 1960s, when the leading edge of the baby boom entered adulthood, everybody fretted over the "generation gap," that seemingly unbridgeable communication chasm between the Greatest Generation and the kids who refused to trust anyone over 30.

Forty-plus years later, an equally massive generation gap is at work, this time with boomers playing the role of angry, uncomprehending parents who rarely miss an opportunity to hector or grossly miscomprehend their children. If the political alliances of the past—especially the Democratic and Republican parties—are failing to capture the hearts and minds of millennials, a major part of the reason is that our political language is still stuck in the 1970s. Older conservatives, liberals, progressives, and libertarians invoke abstract phrases such as socialism, big government, and capitalism the way previous generations over-relied on such bygone milestones as McCarthyism, the Scopes Trial, and the Spanish Civil War. They are with-us-or-against-us phrases referencing events that just don't have meaning for younger people.

For people living during a time when an entity known as the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics not only existed but spearheaded a seemingly plausible alternative to liberal, market-based democracies, talking about socialism, capitalism, and big government made all the sense in the world. But as the world's self-styled socialist states dwindle into the low single digits, it's not at all clear what socialism means or what threat it poses to the American way of life.

Similarly, the heyday of big government as either an unironic positive descriptor or dismissive canard may have peaked during the Reagan era. Is capitalism what they do at Whole Foods or is it what they do in coal mines? Millennials do not have memories of the Soviet Union; the long-challenged victory of capitalism—of a market-based economy—is axiomatic in their lives. As such, they have little to no idea what their parents and older siblings even mean when they deploy such jargon in political arguments. Even when we all use the same words, we are having very different conversations.

In a 2010 CBS/New York Times poll, just 16 percent of millennials defined socialism as the government owning the means of economic production. (About 30 percent of older Americans used that definition.) That's not a deficiency in American education; it's simply a sign that the Cold War is over. No one expects auto mechanics in an age of fuel-injection engines to give a rip about old-style carburetors. Yet the mismatch in language used by different generations causes all sorts of communication problems.

The Reason-Rupe poll, for example, found that 42 percent of millennials "prefer" socialism as an economic and political system, a result that can send shivers down the spines of older anti-communists. Yet when things are put in a language that millennials actually use, a very different picture emerges. When the Reason-Rupe poll asked millennials whether they preferred a free market economy or one managed by the government, the younger-generation's diapers looked considerably less red: 64 percent prefer a free market, compared to just 32 percent who favor state management. As befits a generation known for producing a growing list of billionaire entrepreneurs, millennials have highly positive visions of business, with 55 percent saying that they'd like to start their own some day.

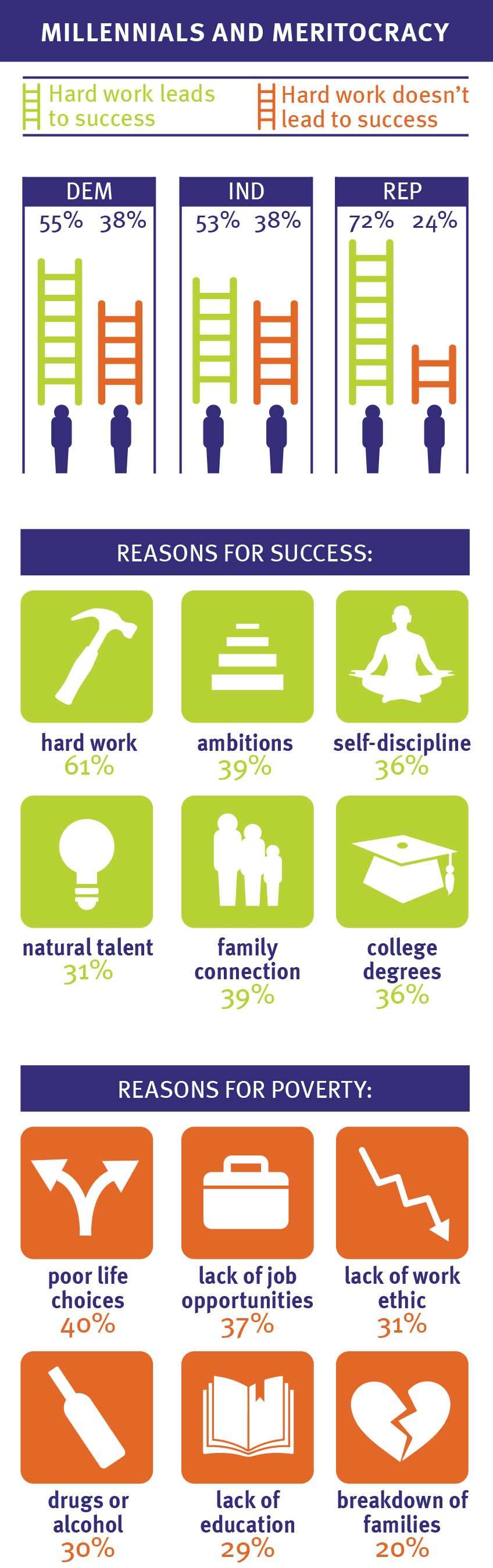

About six in 10 millennials say that most people can get ahead with hard work, a figure similar to that of older Americans. Also like older Americans, millennials hold individuals chiefly responsible for their own life outcomes. A majority define fairness not as splitting up society's wealth equally, but as making sure that the people who work the hardest get to keep their earnings, even if that means unequal outcomes.

(Article continues below)

They are also highly skeptical of government action. Fully two-thirds say that government is usually inefficient and wasteful. That's up from just 42 percent in 2009, at the dawning of the Age of Obama. Sixty-three percent of millennials say that regulators are in the hip pocket of special interests, and 58 percent agree that government agencies and bureaucrats generally abuse their power. Not occasionally, generally.

Such anti-government attitudes may warm libertarian hearts, but it would be a major mistake to think that millennials are the second coming of Murray Rothbard-style anarchism or even Reaganesque disdain for government solutions. While millennials clearly prefer free markets to state-managed ones, they are split on whether free markets are better at promoting economic mobility (37 percent) than are government programs (36 percent). Seven in 10 support government guarantees for housing, health care, education, and income for the truly needy. Yet almost as many—65 percent—think overall government spending should be reduced, and 58 percent favor cutting taxes.

From the point of view of older Americans and the political identities they inhabit, such seeming contradictions—government should guarantee income but cut spending?—come across as the folly of youth, an inability to hash out a coherent, systematic ideology. That sort of response will doubtless allow Republicans, Democrats, conservatives, liberals, libertarians, and progressives to keep selling what they've been selling for decades with minimal changes.

But what that traditional political language and ideology won't do is what it desperately desires: reach millennials. (See "The Millennial Scramble," page 30) When it comes to politics, Generation Independent is already tuning out their boomer and Gen X elders like so much Bob Seger on their parents' car radios.

That is as it should be. The future always belongs to the young, who must find their own way in the world. Yet it would be a shame if this new generation gap gets in the way of the sort of trans-generational solidarity that could make the future so much easier for all of us to navigate.

Reforming or (better yet) abolishing the old-age entitlement programs that threaten the economic future will be best accomplished if every generation can speak clearly to one another about a transfer-payment system that is enriching the old and wealthy at the expense of the comparatively poorer youth. And the oldest Americans can certainly learn a few things about tolerance and government neutrality from those nose-ringed layabouts napping on the couch.

Whether or not the Democrats or Republicans can widen their worldviews and engage them meaningfully, millennials are getting on with their lives. Like fun. at the Grammys, they have thanked their parents and those who came before. They rummage through past generations' experiences and attitudes like Gen Xers used to rummage through Salvation Army stores. Mostly, though, millennials aren't listening to you, because you're not speaking a language that makes sense to them. They are young, they want to set the world on fire, and they can—and will—burn brighter than the sun without asking anyone else's permission.

Nick Gillespie (gillespie@reason.com) is editor in chief of reason.com and Reason TV. Emily Ekins (emily.ekins@reason.org) is polling director for the Reason Foundation's Reason-Rupe Public Opinion Survey.