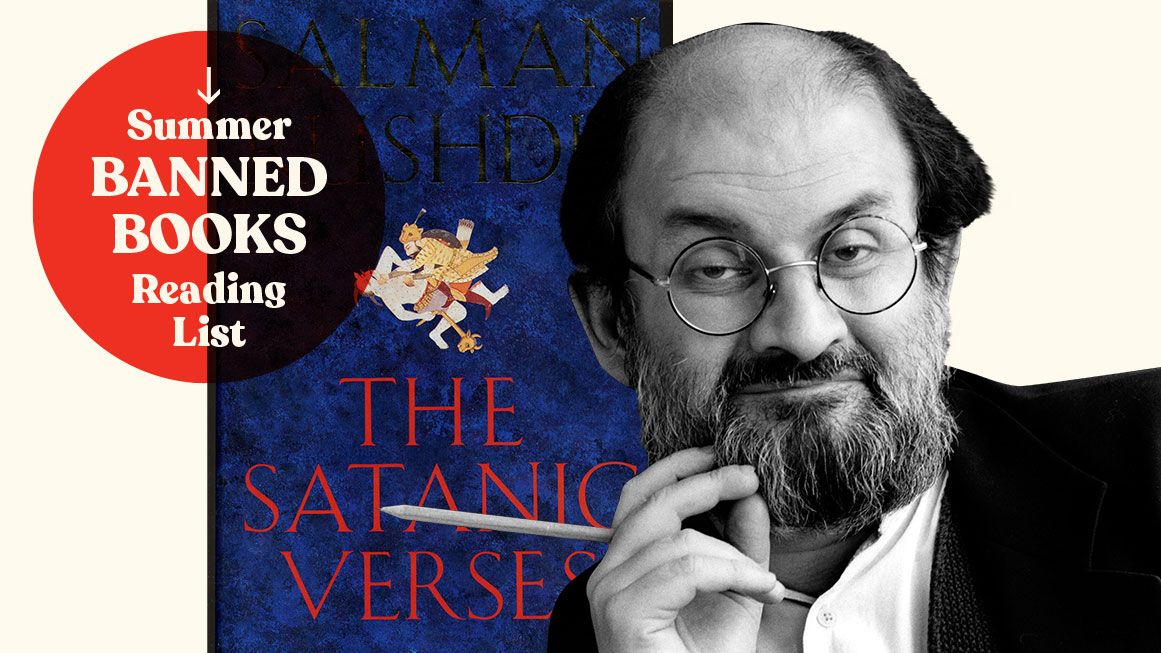

Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses Enraged the Muslim World

In 1989, Iranian leader Ayatollah Khomeini called for the author and those involved in the book's publication to be put to death.

The fallout from Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses (1988) was even more bizarre and terrifying than the novel's opening sequence, in which a hijacked plane flying from India to Britain explodes over the English Channel and the two protagonists, Gibreel and Saladin, are transformed into an archangel and devil, respectively.

While Gibreel—who has been transformed into the archangel Gabriel—falls into the Atlantic, he has several dreams, including one about an alternate-universe founding of Islam by a man named Mahound. (Mahound, another name for Muhammad, was used by Christians in the Middle Ages.) In these visions, the emerging religion allows the worship of several goddesses, and doubt is cast on the divine nature of the prophet's words. Rushdie went so far as to name the book's prostitute characters after Muhammad's wives.

Readers later learn that these visions were sent by the devil. But the fun house–mirror image of Islam nevertheless angered much of the Muslim world. In 1989, Iranian leader Ayatollah Khomeini called for the author and those involved in the book's publication to be put to death. Clerics and government officials were, in essence, instructing Muslims to hunt and kill Rushdie, with Islamic organizations closely aligned with the government placing a $2.5 million bounty on his head.

The consequences were grim. Rushdie was put under police protection at his home in the United Kingdom for the better part of a decade. Hitoshi Igarashi, a Japanese translator for the book, was killed by an unknown attacker in 1991. An Italian translator of the book named Ettore Capriolo was stabbed (but did not die from his wounds) that same year. Aziz Nesin, a Turkish translator, was attacked by arsonists while praying with others; the fire killed 37 people, though Nesin survived.

In 1989, India banned the book, deeming it hate speech. "These persons, whom I do not hesitate to call extremists, even fundamentalists, have attacked me and my novel while stating that they had no need actually to read it," wrote Rushdie in The New York Times. "That the Government should have given in to such figures is profoundly disturbing." He noted that India's parliament described the ban as a "pre-emptive measure," since "certain passages had been identified as susceptible to distortion and misuse, presumably by unscrupulous religious fanatics and such. The banning order had been issued to prevent this misuse."

Rushdie summed up the government's tortured logic: "It is as though, having identified an innocent person as a likely target for assault by muggers or rapists, you were to put that person in jail for protection."

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Satanic Verses."

Show Comments (347)