On the Pride Parade Route With the Libertarian Hoping To Challenge Marjorie Taylor Greene

Angela Pence is running against the controversial Republican congresswoman, but first she has to clear Georgia's anticompetitive ballot access requirements.

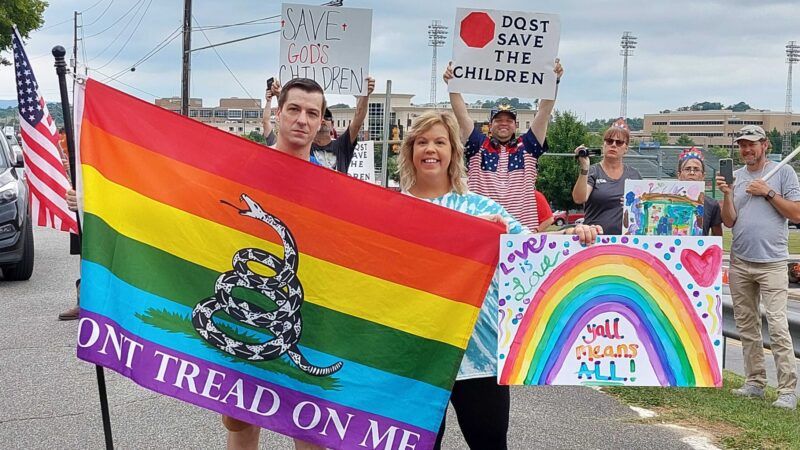

"I'm at city hall," Angela Pence says via text message. "By a guy with a 'Don't Tread on Me' flag."

Even amid the vibrant scene along Broad Street in Rome, Georgia, on Saturday morning, the modified Gadsden flag—a rainbow-colored one, but with the familiar coiled rattlesnake and slogan—stands out. Before crossing the street to meet Pence, however, I have to make way for a drag queen riding in the bed of a bright red pickup truck and fist-pumping along to a blaring Lady Gaga song. It's a message of defiance as subtle as the rainbow-colored Gadsden flag—particularly here, at the first-ever Pride parade in Rome, a city of about 37,000 nestled in the state's deeply conservative northwest corner.

Pence is a part of that spirit of defiance even as she is hoping to capitalize upon it. A political novice, Pence is running for U.S. Congress as a Libertarian against incumbent Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, the controversial first-term congresswoman who in many ways embodies the GOP's post-2016 fixation with culture war politics and conspiracy theories.

Earlier this month, Greene warned that straight people could go extinct "probably within about four or five generations." In another tweet, Greene claimed that "an entire #PrideMonth and millions in spending through corporations & our government on LGBTQ sexual identity needs to end." Against that backdrop, simply showing up to an event like this sends a message.

Before Pence can even start a real campaign, however, she has to gather more than 23,000 signatures from registered voters in Georgia's 14th congressional district by July 12 in order to satisfy the state's difficult ballot access rules. She came to Rome on Saturday hoping to gather some of that total. It's tedious work, one that requires volunteers to carry clipboards and the willingness to explain—over and over again—how the state's ballot access laws work to people who may not care.

"I think the people here deserve to have another choice," she tells me as we walk with a few hundred other parade-goers, heading for a small park along the Coosa River where the rest of the day's festivities are planned. Once there, she circulates among the attendees and vendors, working with a handful of volunteers and friends who have come along to help collect signatures.

Often, all she has to do is mention that she's running against Greene to get attention, though Saturday's parade is not a true cross-section of a district that President Donald Trump won by more than 50 points last year despite narrowly losing the state as a whole. (When Trump wanted to hold a post-election rally in Georgia to pressure the state's officials into reversing the outcome, the event was held at an airstrip not far from Rome.)

"Realistically, Democrats don't have a chance here," Pence repeatedly tells people. A Libertarian might not either, but arguably might have a better shot of carrying the district's few blue spots (like Rome, where Trump lost every precinct in 2020) while also engaging Republicans who are fed up with Greene or open to a true small-government message.

If the state will let her on the ballot, that is. In all likelihood, Pence's effort will fail, and a ballot access law will once again deserve credit for protecting an incumbent.

There's not much love for the incumbent on display Saturday. "I came to this just because it is in Marjorie Taylor Greene's district," says Melanie Kelly, who lives in Atlanta. Her wife, Krista, is open-carrying a pink and white AR-15 at the parade—the most ostentatious, but not the only, celebration of the Second Amendment at Rome's Pride event.

The Pride parade and the visitors it attracts to Rome illustrate the changing cultural tides in northwest Georgia—even in a place that's undoubtedly Trump country. "This could never have happened here" 10 or 15 years ago is a common refrain when I ask people to share their thoughts on the city's first Pride parade. It's easy to see how some conservatives, like those holding protest signs along the parade route, could interpret this as a triumphant march of progressive ideology that until recently was contained to more urban areas and specific subcultures. The mainstreaming of LGBT culture means a higher level of acceptance of individual autonomy and human freedom, but it's also generated a political reaction that increasingly defines the conservative movement—and one that encourages the wielding of government power to limit the self-expression and free choices of others.

It's been three years since commentator Sohrab Ahmari, then an editor at the New York Post, set off a conservative schism by calling out conservatives like The Dispatch's David French for being insufficiently militant towards drag events that include children. In that time, "drag queen story hour" has become a source of viral rage for a segment of the political right. Greene recently escalated the rage into a threat of using actual government force by announcing her intention to introduce a bill banning drag events that include children.

"This needs to be illegal," she said earlier this month. "What's the difference in children stuffing cash in a drag queen bra and a stripper's bra? Nothing. It's wrong and it's indoctrination."

Rome's Pride festival included a drag queen story hour.

"I don't see what the harm is in drag queens reading stories to kids. Politicians do it all the time," Pence says with a shrug, though she also draws a line between events where reading is the main activity and taking kids to outright drag shows where provocative dancing might be the focus. "I think that if parents want to take their kids to a drag queen story hour, that's their choice to make," she says.

It's the kind of sentiment that probably needs a more prominent place in our civic discourse—one fundamentally at odds with the notion that members of Congress should get to decide how anyone raises their kids. Later, when Pence crosses paths with India Mills, the head of a local drag troupe and the queen who'd led the parade down Broad Street from the back of a pickup truck, the two share a quick laugh about the heat ruining their makeup.

The fact that Rome's parade attracts crowds from outside the area actually complicates Pence's effort to get on the ballot here. Only signatures from registered voters who reside in the district count toward the tally she needs, which means her volunteers have to collect addresses as well and check them against the state's voter rolls. With redistricting having been completed in Georgia only a few months ago, she says, lots of people aren't even sure which district they reside in now.

But Pence is determined to work it. The monthslong effort to get enough signatures to become the first third-party candidate to qualify for a congressional race in Georgia since the 1950s requires the kind of grit that she might have learned from an earlier career as a professional dancer—"Fighters Keep Fighting" reads the tattoo on her right arm, the letters intertwined with a pair of pointe shoes—or perhaps from being a mother of eight children, all of which Pence homeschools. (A ninth is on the way, due in January.)

Even if the effort ends in failure, it's worth it for the party to pursue races in what would otherwise be single-party districts with high-profile incumbents, argues Chase Oliver, the man carrying the rainbow-colored Gadsden flag and marching alongside Pence. He's the Libertarian Party's (L.P.) candidate for U.S. Senate in Georgia—and he's already on the ballot since the L.P. has done well enough in recent elections to secure automatic ballot access for statewide candidates. Bizarrely, it's more difficult to get on the ballot for a state legislative or congressional race than for a gubernatorial or senatorial race in Georgia.

"I call them 'the sexy races,'" Oliver says. "Having people run for those offices raises awareness about the party and helps us recruit and compete in lower-level races too."

Among some longtime L.P. types, there is concern that the party's new leadership will shy away from backing candidates like Pence who are challenging conservatives. Oliver specifically expresses frustration over some of the maneuvers at the recent Libertarian national convention, where the party's delegates voted to remove a longstanding plank in the L.P.'s platform condemning bigotry as "irrational and repugnant." But circulating within traditionally left-wing spaces, like Pride events, and pushing for a society that's more accepting of self-expression and individuality has always been foundational for libertarians, he argues.

"I'm trying to remain myself in this whole sea of people who constantly want me to be something else," Pence tells the owner of the Frisky Biscuit, a Rome-based sex shop, who is enthusiastic about signing a ballot petition for someone to be challenging Greene.

She could be talking about her place in the broader spectrum of Libertarian politics or her status as the ultimate outsider in a congressional district where the outcome of November's election is practically assured by a combination of ballot access laws and partisan redistricting.

The local entrepreneur signs as Pence wraps up her pitch: "We're here to fuck up the system."