South Carolina Will Let This Hospital Bypass Its Certificate of Need Laws, but That's It

Another example of the infuriating cronyism behind CON regulations, which won't apply to a well-established hospital in Charleston that's looking to move.

In the same state where health care regulators once held up construction of a new hospital for more than a decade, state lawmakers are on the brink of exempting one proposed new hospital from those same onerous, anticompetitive requirements.

One hospital, that is. Just one. The regulations themselves will remain on the books and will apply to everyone else.

The exemption is buried deep within an appropriations bill that could get a final vote as early as Wednesday, when state lawmakers will convene to pass the annual budget. "For the current fiscal year, the relocation of a licensed hospital in the same county in which the hospital is currently located shall be permitted," the bill reads, in part.

Normally, such permission is granted via the state's Certificate of Need (CON) process, overseen by the Department of Health and Environmental Control. It was that same permitting process that held up the construction of a new hospital in Fort Mill, South Carolina, for well over a decade, as Reason has previously reported. By inserting these few lines into the appropriations bill, lawmakers are creating a special loophole in those rules.

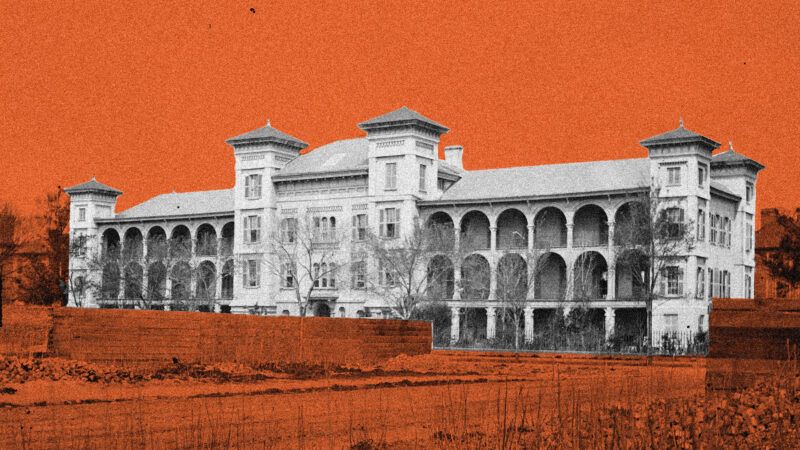

Though it isn't immediately obvious from the text of the bill, the hospital that seems likely to benefit from the exemption is Roper St. Francis Healthcare, which announced plans last year to spend $500 million relocating from downtown Charleston to another part of the city. To say that Roper is a Charleston institution is probably an understatement: the hospital has been around for so long that wounded Civil War soldiers were treated there.

The relocation makes sense. Hospital executives told The Post and Courier newspaper last year that the growing city requires a more modern hospital that's more centrally located (downtown Charleston is on a small peninsula, but much of the city's more recent growth has been outside of that area).

But the project ran the risk of being tangled in CON-related red tape, the paper noted back in November: "Many of the key components of the 2030 initiative will require approval through the S.C. Department of Health and Environmental Control's Certificate of Need program, which is set up to evaluate plans for new hospitals and hospital growth. Not only will Roper St. Francis need to make a regulatory case for these plans, history shows it will also likely face pushback from competing hospital systems in the region."

If the relocation means better care and easier access for patients, then state lawmakers are probably doing the right thing by making sure that the project isn't subject to the time-consuming, expensive litigation associated with navigating the CON review process.

But if that's true for this hospital in this situation, isn't it true for hospitals around the rest of South Carolina too? An established hospital getting to make an end-run around the same rules that are often used to keep new competitors out of the health care market is a useful illustration of what critics often say about CON laws: that they are crony arrangements meant to benefit incumbent providers even at the expense of patients.

"Not only is this 'CON for thee, but not for me' the height of hypocrisy—it's corporate welfare that shields politically-connected hospitals from competition that would drive down prices and increase access to quality healthcare for South Carolinians in need," says Candace Carroll, the state director for Americans for Prosperity, a free market group that's advocated for CON reforms.

The special carve-out in the budget bill is even more infuriating because there seems to be a broad bipartisan agreement in the South Carolina legislature that the state's CON laws need fixing. A bill to eliminate South Carolina's CON regulations for all health care facilities except nursing homes cleared the state Senate with a 35–6 vote in January. It was left to rot in a House committee and now will not receive a vote before the next legislative session, when the bill will have to start from scratch.

If that bill had become law, it would have cleared the way for 28 projects that are currently tied up in legal battles despite having won preliminary CON approval, according to the Post and Courier. Another 34 projects awaiting review by the state's Department of Health and Environmental Control would be able to proceed as well. The paper estimates that those delayed projects represent more than $1 billion in health care investment in the state.

And that doesn't include the loss of projects that never materialized in the first place. A recent report found that 25 percent of South Carolina CON applications during a recent three-year period were denied or withdrawn after being submitted. Those applications represented more than $450 million of investment in the state that never occurred—simply because regulators got in the way, or because competitors would have objected.

Instead of getting more robust, competitive, and accessible health care, South Carolinians will continue to suffer—and suffer is not an exaggeration, since strict CON laws for health care services are correlated with poorer health outcomes—under a regulatory regime that even the head of the South Carolina Hospital Association has admitted "does not serve the community."

Meanwhile, at least one prominent, politically connected hospital was able to get a special break from state lawmakers. Must be nice.

Show Comments (6)