The U.S. Prison System Has Reached 1,000 COVID-19 Deaths

The infection and death rates have surpassed those of the general population.

America crossed a grim threshold this week. The Marshall Project and the Associated Press calculate that there have now been 1,000 COVID-19 deaths across the state and federal prison systems. Of the people who died, 928 were inmates and 72 were prison staff.

There have been at least 108,000 reported COVID-19 infections among inmates, and the rates can vary wildly from state to state: Less than 10 percent of California's prison population has reported infections, while 30 percent of Arkansas' population has. You probably shouldn't use those numbers alone to determine how effectively prisons have responded to the outbreak: There are other variables, like how long it took for prisons to start widespread testing and how they've managed the infections. There has been a big spike in newly reported infections in prisons in July and August, but reported deaths are stable and about half what they were in April and May.

Research published in early July found that COVID-19 infection rates among prisoners were 5.5 times that of the general population. The death rate (39 per 10,000) among inmates was also higher than the death rate (29 per 10,000) among the general population. Again, this can vary wildly from state to state. Some states, such as Pennsylvania, report lower infection and death rates among its inmates than in the general population.

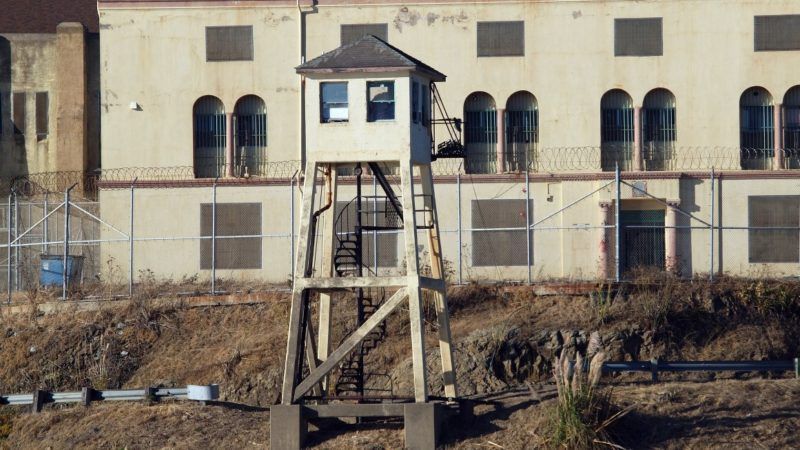

In California, the consequences of poor prison COVID policies are still playing out in San Quentin State Prison. California's oldest prison had been doing very well at keeping the coronavirus at bay, reporting no infections at all until May. But that month, several prisoners were transferred to San Quentin from the Correctional Institute for Men in Chino. The Chino prison had seen a massive outbreak and several deaths, and this was supposed to relieve overcrowding. But the transferred prisoners were not properly tested and quarantined, and so San Quentin had an outbreak too.

When Reason first noted this new infection cluster at the end of June, there had not yet been any COVID-19 deaths at San Quentin. Now, less than 90 days later, there have been 26 deaths, and San Quention has bypassed Chino to have most deaths among inmates in the state. This month a San Quentin prison guard also died of COVID-19.

When we critique politicians who try to shower themselves with undeserved glory for their COVID-19 responses, like New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, we tend to focus on their poor grasp of risks at both ends of the spectrum—in Cuomo's case, pushing the infected elderly into nursing homes while shutting down parks and other outdoor spaces. The problems in the prisons deserve more attention, but it often takes a back seat because of people's attitudes toward prisoners.

But prisoners are in a position where they depend almost completely on government competence in a pandemic for their survival. And this should matter to you even if you don't particularly care about criminal justice reform (though it's certainly worth thinking about the facts that almost all of our biggest infection clusters are in prisons and that America has the world's highest incarceration rate). The people who are most dependent on government competence are getting infected at a higher rate and dying at a higher rate than those who are not. What does that tell you?

Show Comments (41)