A Quiet Night in Portland

The J.V. squad was out looking for trouble and the battle over who counts as press continues.

C. programs her camera glasses. She's covered dozens of Portland protests, had her equipment stolen, had people rough her up.

"They don't like to be photographed," she says, "they" meaning the various young people who've confronted law enforcement nightly since the killing of George Floyd.

Our first stop of Thursday night, however, is peaceful, watching a young black man in a gray hoodie on a mic in park a few blocks from where the usual action is.

"I come here to speak to you today about self-accountability," Xaii Kuu says, explaining to a smattering of people that he's been told variously that he's an Uncle Tom, that he doesn't go about protesting the right way, that he should die.

"We gotta watch for how we deal with those who do not agree," he says. "We say we're out here for Black Lives Matter? We're here because another group, another race of people, said, 'Nah, fuck them.' And every time we do that? In any capacity? We do the exact same thing."

There's soft applause, a marked change from the fence-shaking and window-breaking, the tear gas and rubber bullets, exchanged for weeks between protestors and federal and local forces, at the federal courthouse and on the streets of Portland.

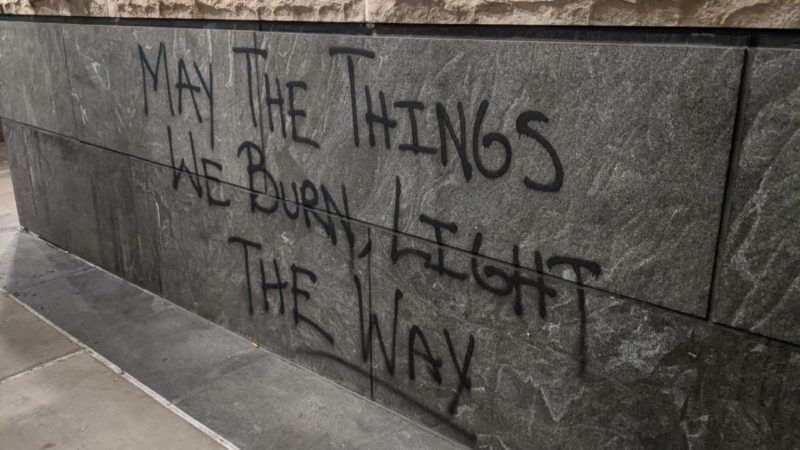

Things quieted somewhat after the feds mostly pulled out—there was no avenue for them to "win," and the protesters were not backing down, were in fact gaining local sympathy. I did not trust it, did not see how the energy and momentum could go flat. Why would it when it was working? The movement, peaceful and not, had achieved at least one of its stated goals, to make sure the police had less authority. A day earlier, the brand-new progressive D.A., who'd won with 77 percent of the vote, announced that the majority of the people arrested since the protests began would not be prosecuted. Call it special protections for protest-related cases, a tacit endorsement of those Portlanders who felt a more fair and equitable future required damaging property and setting fires.

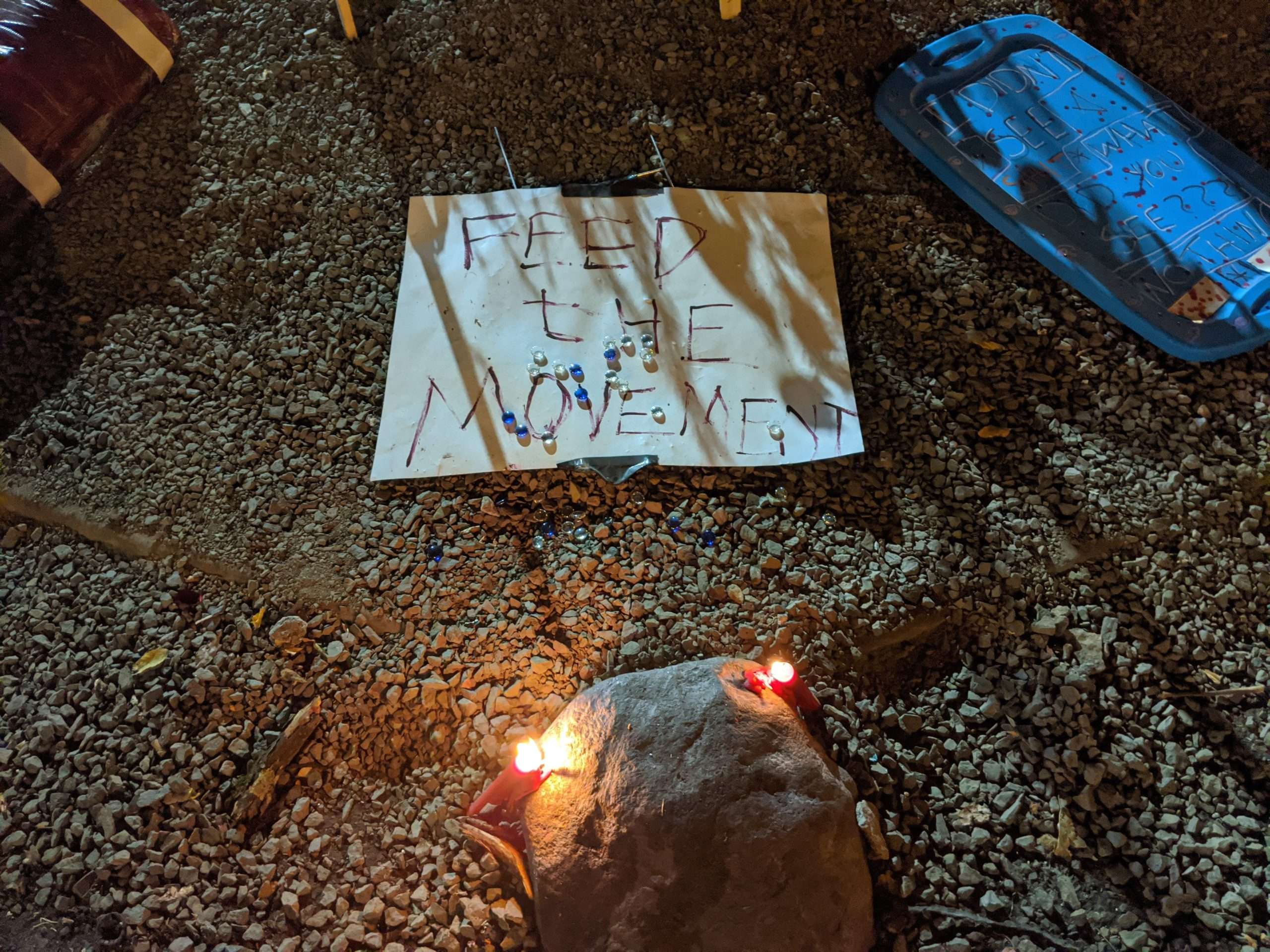

That drive is not much in evidence tonight. There are maybe 200 young people loitering near the federal courthouse and Justice Center, the city's main police bureau. A Ford Focus in the middle of the street has a speaker on its trunk blasting Common's "Letter to the Free." Where a bronze elk statue once stood, there's a pile of commemorative drawings, one of which reads, "Feed the Movement." That feeding tonight feels thin, mingy, and frankly everything is too quiet.

"It's ominous," reads a text from inside Justice Center. It's from a police employee I've written about before, a woman who'd been trapped in the building's basement when protesters set fire to the building May 29.

"We are all really perplexed," her texts continued. "Are they resting up for tomorrow night?"

"Let's go around the back," says C. The street here is dead quiet, no protestors, no pedestrians, only a lone cop sitting in the Justice Center lobby. Why does he have the door open?

"Because they came last night and threw feces and diarrhea in here," he says, above the whirr of an industrial fan trying to blow out the stench.

"What happened, what happened?" asks a group of five teenagers, who, when told, make a show of laughing. They're not black bloc anarchists, they're random kids with random energy who came to engage, maybe, in some light taunting of a police officer. The J.V. team. Finding him talking to two middle-aged women, they slink back to the corner, then advance, then fall back again as they make way for the varsity squad, such as it is.

"Quit your job!" shout the two young people. It's a stock refrain. Still, I ask them, why did they say it?

The young people stop. They are in the black bloc uniform—black clothes, black face mask, black helmet. And yet there is something patrician about them. The boy reminds me of Benedict Cumberbatch; the girl is fine-featured above her mask. It's as if, under different circumstances, one might encounter them at cotillion.

"Do you believe that property is worth more than human lives?" asks the boy.

What?

"Do you believe the police should be allowed to murder people?" asks the girl.

Is that what's been happening in Portland, the police murdering people?

"The entire police force is built on systemic racism," she says. "On keeping black people down."

"We've tried for 20 years to do it another way," says the boy, who is maybe 22. "It hasn't worked. Nothing changes except with violence."

Like setting fire to Justice Center while there were people inside, including black people?

"But those people were illegally arrested by the police," says the girl.

I meant the black people that work inside.

"They're part of the problem," she says.

Is there a flicker of interest when I ask if she's familiar with the German youth movement of 1968, how the Baader-Meinhof Group sought to correct the sins of their Nazi parents through escalating acts of violence? Maybe. Then it goes out. She says something about people doing what they need to do.

We'll have to agree to disagree that using the tactics you decry in your perceived enemies is the way to a utopian future.

"No, I will not agree to disagree with you when it comes to racism, but you have a nice night," she says and walks off. The boy flips me the bird.

"It's too quiet," says C., checking her phone.

"Feeling a little let down because tonight is a quiet night in Portland?" tweets @AntifAnonSupplies. "Use it to rest up for tomorrow's Direct Action March. Fuck your peace policing. Let people be angry."

"How you doin'?" asks a girl carrying a steel baton. "New normal life now."

Normal meaning patrolling the police station at midnight with a baton. Normal meaning that when there are two loud booms a moment later—maybe mortars, maybe flash bangs—people barely react. It's night 77, after all.

The 200 in front of the Justice Center don't seem to know what to do. Half of them wear PRESS taped to or spray-painted on their clothes. Local measures forbid police from interfering with the press, ergo, anyone who wants to be is press. People film incessantly, and those suspected of not spreading the right message can have their camera taken away.

"YOU'RE NOT ALLOWED TO FILM!" shouts one of the girls in an altercation I'm getting on video. It's more girlfight-on-a-hot-August-night than political battle, still, everyone uses the same verbiage, believing it to be blanket protection. As I keep filming regardless, my phone is snatched by a scrawny white kid in a hot pink shirt. C. lunges for him and they both go down, but he's faster on the rise and jets around the corner.

Two girls are immediately in my face. "You're not allowed to film!" one shouts.

Who told her that? I'm allowed to film anything I want.

"Get out of here," the second girl says. "This is not your fight, you wouldn't get it, you're old."

If by this she means not seeing the efficacy of shitting in a communal bucket, point taken.

"We gotta get out of here," says C., her eyes flicking toward five masked people not so much moving our way but wanting us to know, by their posture, that they're there; that these are their streets now.

But my phone!

"He went around the corner," says C., and just as we make the turn, a black kid comes rolling up on a one-wheel skateboard.

"I got your phone," he says, and hands it to me.

What? How?

"I told him to give it to me," he says, like no big deal. "He said to just erase what you filmed."

He rolls off before I can finish thanking him profusely.

"He has more sense than the guy who took it," says C. "He knows stealing your phone does nothing to help the cause."

I will never know how one-wheel knew the phone was mine, if he saw it get swiped and followed the kid, whether there's an "honor among thieves" ethos at play, whether things are more choreographed than meets the eye. I don't have much faith that such choreography, and its keenness to have others feel the sharp end of the stick, will lead to many such acts of grace.