The Missouri A.G. Is Advocating for the McCloskeys' Civil Liberties. What About Lamar Johnson's?

What is the state's position when an innocent man spends 25 years in prison?

Last month, Mark and Patricia McCloskey were captured on video aiming guns towards anti-police brutality protesters after the protesters breached the gate to their private neighborhood. On Monday, St. Louis Circuit Attorney Kimberly M. Gardner—the city's elected head prosecutor and a Democrat—filed felony charges against the couple for the unlawful use of a weapon.

Gardner's decision to charge the couple despite the fact that they did not fire their guns, no protesters were injured, and the couple did not leave their own private property led Missouri Attorney General Eric Schmitt, a Republican, to file a brief saying that the couple was free to defend their property under the state's "castle doctrine."

"There is a common law interest if the attorney general feels that the broader interest of Missourians are affected, like the chilling effect that this might have with people exercising their Second Amendment rights," Schmitt told the St. Louis-Dispatch. "We felt it was important to get it in and make the state's position known early."

The conflict between Schmitt and Gardner over the McCloskeys is an inverse mirror to their conflict over Lamar Johnson. Between the two cases, neither prosecutor appears to be consistently applying their own philosophies of discretion and restraint.

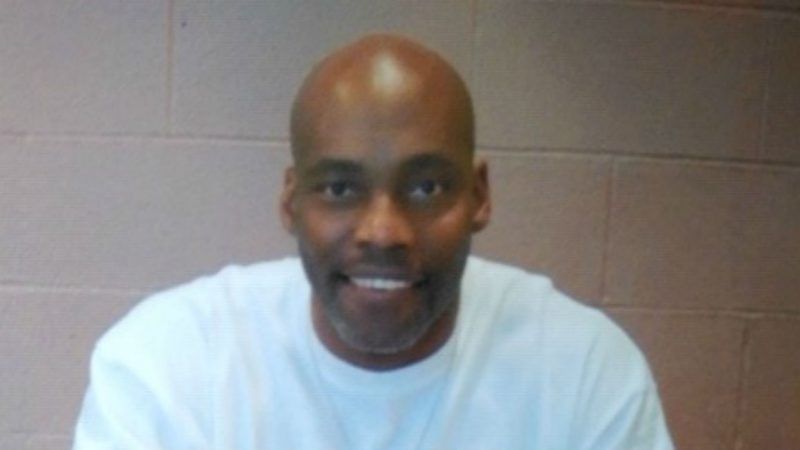

Johnson is now spending his 25th year in prison for the 1994 murder of Marcus Boyd. For Johnson to have killed Boyd, as Reason reported last year, he would have needed to leave an apartment party, travel three miles on foot, commit the murder, and travel back to the same party on foot, all within the span of five minutes. Unfortunately for Johnson, his case was marred by false testimony and Brady violations. According to a 67-page motion for a new trial for Johnson filed by Gardner (which accompanied an exculpatory report from her office's Conviction Integrity Unit), Johnson's conviction was reliant upon "perjured testimony, suppression of exculpatory and material impeachment evidence of secret payments to the sole eyewitness, and undisclosed Brady material related to a jailhouse informant with a history of incentivized cooperation with the State."

Johnson remains in prison despite the fact that the lead detective, Joseph Nickerson, was found to have fabricated parts of his investigation. Nickerson reportedly bribed a witness $4,000 to identify Johnson as the killer at trial. Additionally, Boyd's killers confessed to their crimes and absolved Johnson of any involvement in 1996 and 2002.

While Johnson's innocence claims are supported by Gardner, the Midwest Innocence Project, and many others, he continues to sit behind bars because of a procedural deadline that provides just 15 days after a conviction for the filing of a motion for a new trial. When Gardner attempted to file a motion for a new trial last July, Circuit Judge Elizabeth B. Hogan used the procedural deadline to deny the motion.

Schmitt, meanwhile, opposed a new trial for Johnson solely, he said, because of the filing deadline. What's more, Schmitt also supports a proposed Missouri House bill that would weaken Gardner's prosecutorial discretion by giving Schmitt the power to pursue charges where local prosecutors have already decided the penalties to be unduly harsh.

As with most defendants, the fates of the McCloskeys and Johnson do not rest in the hands of impartial people. But in this case, their odds are doubly bad due to a political beef between a tough-on-crime Republican state attorney general and a reform-minded Democratic city prosecutor.

It is odd and unfortunate that Schmitt believes the dismissal of charges in only one of these cases serves the "broader interest of Missourians," and that Gardner appears to have a similarly exclusive view of when her discretion is appropriate. While these two battle over their respective turfs, Johnson is still set to die in prison for a crime he did not commit and the McCloskeys are facing the wrath of the criminal justice system for threatening violence—but not actually committing it—in order to defend their home.

No matter who wins between Gardner and Schmitt, justice loses.